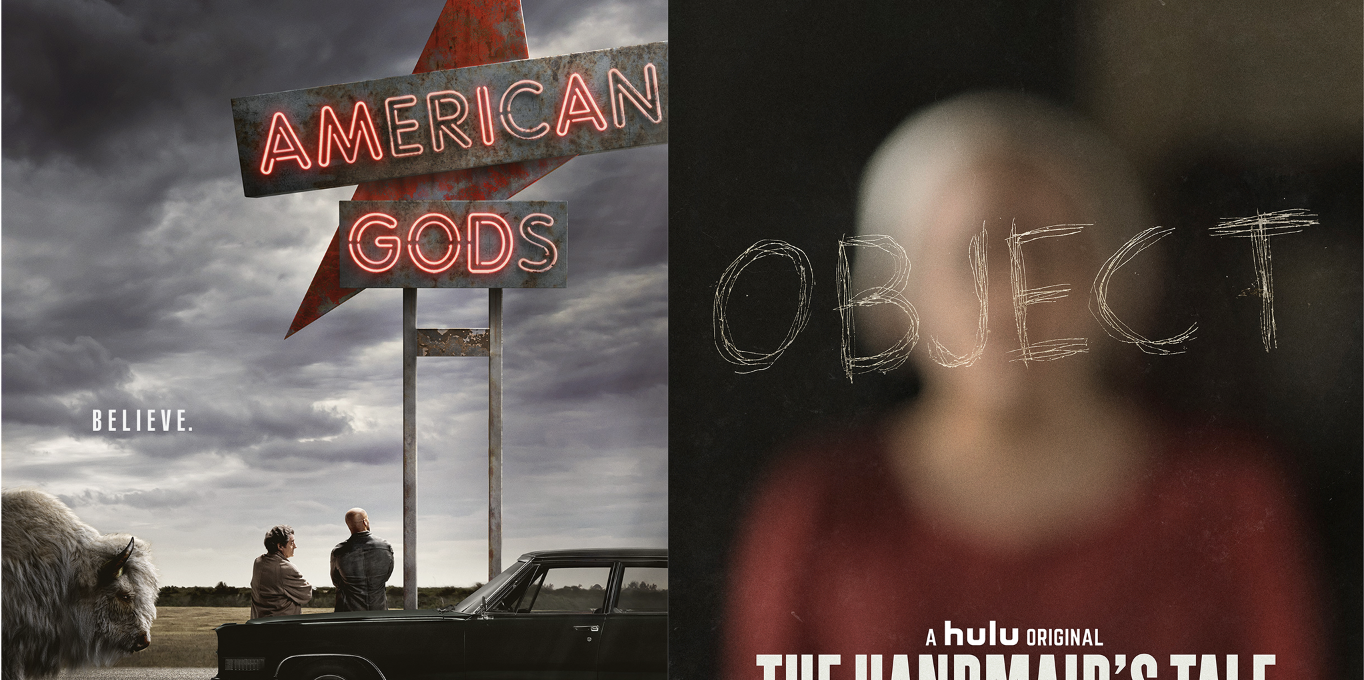

It’s rare that two television series release so close to one another and so prophetically and perfectly speak to the times in which we live. On Wednesday, HULU will release the first three episodes of its adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale. On Sunday, Starz will premiere the first episode of its adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s mythological novel, American Gods. The latter reminds us of who we are in light of our relationship to the divine. The former shows us where we’re bound if we betray those relationships.

As I wrote from SXSW after screening the pilot, American Gods is very much an immigrant narrative, and, here, the gods themselves are the immigrants. Four episodes in and we have yet to see any deity to North America. We’ve seen Norse and African gods, and the gods of technology, fame, and even Easter are on their way. Regardless of where you are on a Friday, Saturday, or Sunday, if you’re worshipping in the United States, you’re likely worshipping a foreign deity.

In the first five minutes of the series, American Gods offers a shocking and grotesque reminder that our devotion shapes not only our daily lives and embodied selves, but the objects of that devotion as well. Their power waxes and wanes with our fervent belief, distractions, and shifting allegiances. What happens to us–and our gods–when we break our covenants, when the bonds of devotion snap?

If I take my immigrant deity (deities?) seriously, I fall in line with a long tradition of covenants and commandments. Yahweh, the god of Israel, consistently commanded Yahweh’s followers to be mindful of the stranger (the foreigner) and to treat them with hospitality, remembering that they were once strangers in Egypt. Fast forward a millenia or so, and you hear echoes of this in Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan and his reminder to his disciples that to the extent they care for “the least of these,” they serve him.

Breaking either one of these commandments doesn’t bode well for Jews or Christians. Just consider one of Yahweh’s warnings for breaking his commandments in Leviticus 26: “‘I will break your proud glory, and I will make your sky like iron and your earth like copper. Your strength shall be spent to no purpose: your land shall not yield its produce, and the trees of the land shall not yield their fruit'” (19-20). For us Christians, we have to reckon with Jesus’ warning in Matthew 25: 45-46, “‘Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’ And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life” (45-46).

Both of these warnings feel eerily descriptive of the world in The Handmaid’s Tale. The events take place in the Republic of Gilead, a totalitarian and theocratic state that has replaced the United States of America (the remnants of that democracy reside in Anchorage, Alaska). The Republic of Gilead is anything but united, as those in power, the Commanders, war with rebel factions across the country. The Republic also suffers from the plague of infertility, which leaders blame on sexual promiscuity and pollution.

To combat this plague, the Republic marries conservative politics and religion to create a new caste system for women, which includes roles of Wives (the highest level), Handmaids (fertile women enslaved to the ruling elite to bear children), and Marthas (infertile domestic servants). In all cases, women are to be seen and not heard. Anyone that would preach a “Gospel” counter to the Republic’s “Quiverfull” message (liberals, doctors, non-Christians, and gays, to name a few) are traitors that must be dealt with publicly and severely. To that end, The Handmaid’s Tale features one of the most powerful examples of scapegoating you’ll see in contemporary pop culture.

The world of The Handmaid’s Tale feels simultaneously distant and horrifically close, and countless critics and commentators have written at length about this. The third episode, “Late,” features extensive flashbacks that reveal how the world changed so fast. Some observers have pointed to the conservatives’ anger over the show, but one hopes that episodes like this don’t give them any more ideas.

The Republic and its treatment of women is heavily influenced by a form of Christianity that many of us know all too well. It is one that ignores its ancient commands to treat our enemies–or those who are just different from us–with more humility and grace than we do now and that, ultimately, the meek do inherit the earth. Like the countless humans in American Gods, we have forgotten our relationship to the divine and what that asks of us. Should we persist in this amnesia, the handmaids tales will be our own.

The first three episodes of The Handmaid’s Tale release on HULU Wednesday, April 26th. Be warned, they are endurance television.

The first episode of American Gods premieres on Starz Sunday night, April 30th, at 9:00 p.m. It’s not for the faint of heart as it features scenes of gore and a truly unprecedented sex scene.