One of the joys of living with a partner who was born and raised in another country is seeing American pop culture again for the first time through his eyes. One night, Fred and I were watching Another Gay Movie, Todd Stephens’ bawdy gay male take on teen sex comedies. Determined to train Fred in the subtle art of camp, I carefully explained the film’s references to Mommie Dearest and Airport 1975.

One of the joys of living with a partner who was born and raised in another country is seeing American pop culture again for the first time through his eyes. One night, Fred and I were watching Another Gay Movie, Todd Stephens’ bawdy gay male take on teen sex comedies. Determined to train Fred in the subtle art of camp, I carefully explained the film’s references to Mommie Dearest and Airport 1975.

At one point in the movie, there’s an extended riff on Carrie. Although I had seen the film, I had a difficult time explaining the camp significance of the Stephen King/Brian DePalma horror story. Why was Carrie “Another Gay Movie?” What is it that draws gay men to this movie that is about menstruation and the frightening power of women’s bodies? I can’t think of any demographic that would know less about the functioning of female anatomy—except for Republican Senate candidates.

Watching the 1976 classic again with Fred, we found some obvious clues to its gay significance. There’s Carrie’s condemnation for her budding sexuality from her deranged Christian mother. I mean, she locks her daughter in a closet, for Christ’s sake. There are themes of being the outcast—the skin-crawling horror many gay men have remembering their high school years and their revenge fantasies against high school bullies.

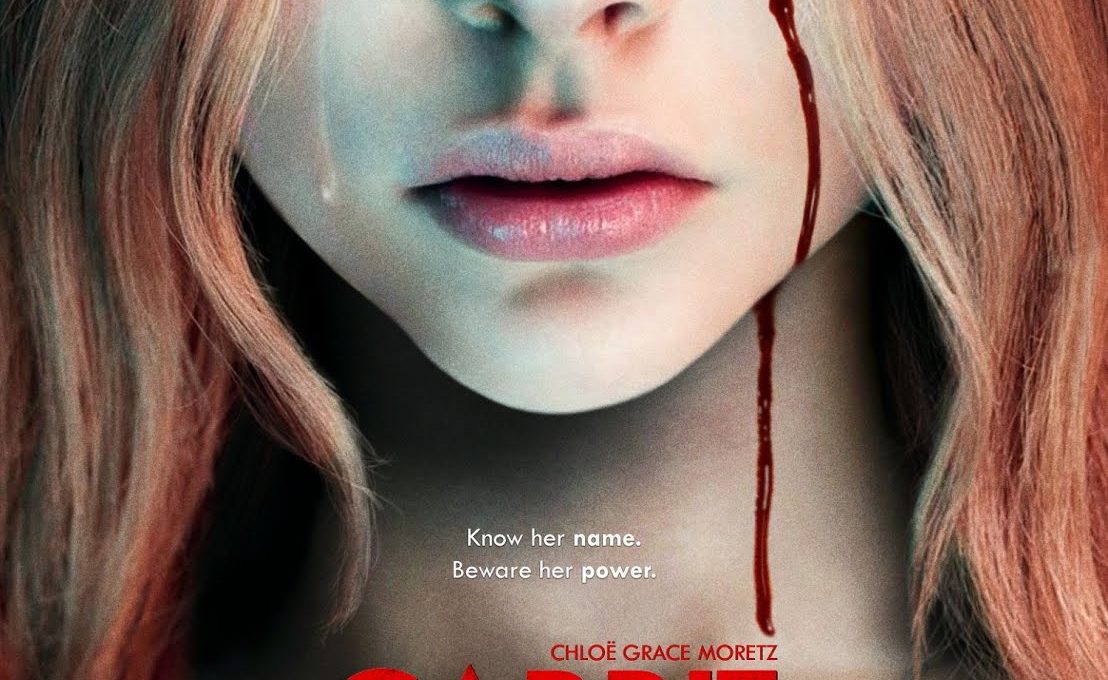

Now the lazy gods of Hollywood, unable to come up with an idea for a new movie, have handed off this iconic American story to one of us for a remake. Well, one of us queers, anyway: Kimberly Pierce, director of the Oscar-winning Boys Don’t Cry (1999). Pierce casts the talented teen actor Chloë Grace Moretz as Carrie and Julianne Moore as her domineering mother, Margaret White.

Pierce, who is a friend of DePalma, was quoted in the New York Times, “I say this with all due respect to Brian, but his film is semicampy.” “Semi?” I cackle maliciously at half a dozen of Carrie’s mother’s lines, especially, “I can see your dirty pillows.” Why would anyone want to take the camp out of Carrie?

Well, for one, because much of it comes at the expense of an innocent and frightened adolescent character, portrayed with supernatural silence by Sissy Spacek. And some of the camp is just, well, creepy, especially the opening scene in which DePalma takes the camera on a slow pan through a giggly, jiggly high school girls’ locker room.

Pierce has no time for the Porky’s shenanigans at the beginning of the film, and gets to the heart of the awkwardness of adolescent bodies in the freak show of P.E. class. Starting with the iconic menstruation scene, Pierce rips into this story with Riot Grrl relish. This time, Carrie is a bullied outsider, but with inner strength. She stands up to her fundamentalist mother and starts to notice, study, and control her powers of telekinesis early in the film.

I’m not satisfied with the portrayal of the mother’s religion in either film. In the DePalma version, Piper Laurie as Margaret White dresses like a Puritan and cheerfully spreads her morbid gospel to the neighbors.

Mrs. White: These are godless times we’re livin’ in Mrs. Snell.

Mrs. Snell [raising a glass]: I’ll drink to that! [Lowers glass sheepishly]

So she acts like a prostletyzing Protestant, but she decorates the White home with crucifixes, images of the Virgin Mary, and a Ken doll Saint Sebastian with glowing eyes. No fundamentalist Protestant would have this kind of idolatrous stuff in her house. It’s almost as though the script’s instructions to the set decorator just said “RELIGION.”

Julianne Moore’s Margaret White is similarly confused about her branch of Christianity. Again, there are the Catholic images and decorations, but she listens to old-time Gospel hymns belted out by Tennessee Ernie Ford. This confusion of religious symbolism leaves Mother White as a rather generic hybrid of all things extreme about religion.

Because Moretz’s Carrie is more empowered, Moore’s Mrs. White seems more isolated. Her abusiveness is directed not just at Carrie but herself, as she scratches and cuts her own arms and legs. Without the gung-ho-for-God camp of Piper Laurie’s performance, Moore’s Mrs. White is as much a figure of pity as piety. She’s mentally ill and spiritually desolate.

Pierce’s film explains things that DePalma’s does not, threading the story more carefully through the various plot points and characters, and giving a clearer background on what happened to Carrie’s mom to make her the way she is. I know it’s uncool and “American” to want things explained to me in a film, but I found this version much easier to follow.

Pierce gives us more clues to high school power couple Sue Snell (Gabriella Wilde) and Tommy Ross’ (Ansel Elgort) motivation for inviting Carrie to the prom. Sue just feels guilty for participating in the girls’ attack on Carrie in the locker room. Yes, this explains something that was left unsaid in the original, perhaps reducing the dramatic tension. But I’d rather have a clear-cut narrative than try to interpret the film through the emotional abstraction that is Amy Irving in the original film.

Pierce is at her best when portraying the danger of misdirected youth careening toward self-destruction and other-destruction. Chris Hargensen (Portia Doubleday) and Billy Nolan (Alex Russell, in the role played by John Travolta in the 1976 film) are terrifyingly determined as the couple preparing the “prank” of dumping pig’s blood on Carrie at the prom. As with Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry, we understand Carrie’s yearning to be accepted in the group, but can see the menace of a sheep being accepted by a pack of wolves.

The climactic scene of dumping the blood and unleashing of Carrie’s powers is no less frightening or gory in the remake. The difference is in the degree of control the Carries have.

In the original film, once doused with blood, Spacek is rigid and shaking, pug nose elevated and sniffing the air like a wet Pekingese, a study in silent terror. When her telekinesis turns violent, she is at the mercy of her powers, unable to stop the destruction that erupts wherever she turns her horrified gaze.

Moretz’s Carrie has been practicing her powers at home. So when she finally snaps, she lifts her arms and directs the destruction around her like a macabre orchestra conductor, deciding with a wave of her hand who to crush and who to sweep out of harm’s way. She is complicit in her powers of annihilation.

This makes the final showdown between Carrie and her mother seem like more of a battle of equals; and somehow, their final destruction seem more fair. Not that the ending seems just or right, but more of an essential of fate when such supernatural powers have been released. Spacek’s Carrie is so much of a victim—of her mother, the bullies, and her powers—that her death seems like the final insult at the hands of the male writers and director.

As for gay men and Carrie, beyond the obvious tropes of fundamentalism and bullying, there is empowerment in embracing one’s “otherness.” The telekinesis that makes Carrie a freak also gives her a sense of identity, and it’s no coincidence that her powers flourish at the moment she reaches sexual maturity.

It’s a lesson hard-earned by gay men or by anyone else who wants to live an integrated life. The thing that seems most scary about us—the monster inside—has to be led out of the dark and embraced in order to be who we really are.