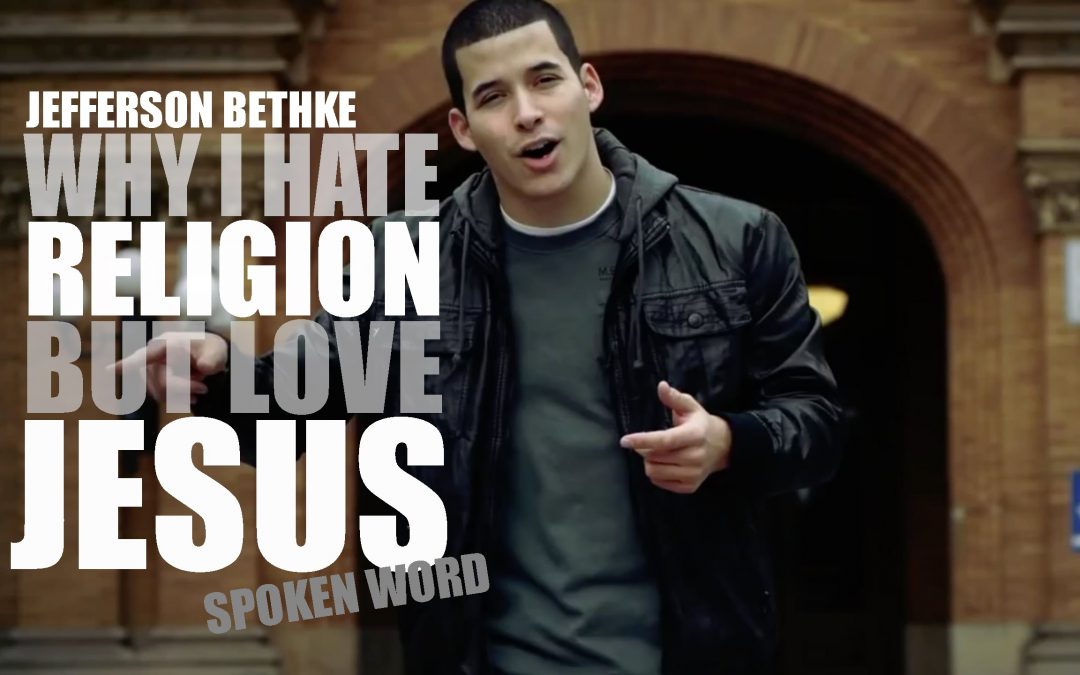

Maybe you’ve heard about it in the traditional media or stumbled on it on YouTube, but one of the hottest viral videos on the ‘Net today is a sermon, delivered in hip-hop/spoken word style by 22 year-old Jefferson Bethke.

The video is called “Why I Hate Religion, But Love Jesus.” It has 21 million views, which has to make it one of the most successful religious videos on the Internet so far.

Bethke starts his rhyme with the seemingly astounding phrase, “What if I told you Jesus came to abolish religion?” He then goes on to rap about how his faith in Jesus transformed his life. This is a classic line that Christians have tried to draw that somehow following Christ destroys the trappings of religion and leads us into a “pure” relationship with God. It’s pretty contradictory on its face, and I’ll point out just a few reasons why, quoting a few words from the poem.

Among the things Bethke mentions that he used to be into before he found Christ were drinking, sex, and pornography:

“See this was me too, but no one seemed to be onto me/ Acting like a church kid, while addicted to pornography./ See on Sunday I’d go to church, but on Saturday gettin’ faded,/ actin’ as if I was simply created to have sex and get wasted.”

If he had addiction problems and found a way out, it’s all good enough, but some of us might call his newfound behavior a Christian ethic: in other words, the ethic you develop when you follow the religion of Christianity. If we’re just going to follow the first century man from Nazareth, he wasn’t actually against drinking. In fact, one of his miracles seems to suggest he was pretty much pro-drinking. Jesus didn’t say anything about porn, which absolutely did exist at the time. (Judea was occupied by the Romans, you can’t tell me he’d never seen it.) And as for sex, well, both Jesus and Paul were rather against it if you could avoid it. Better to stay celibate and await the Kingdom. This included avoiding marriage.

“See I spent my whole life building this façade of neatness/ but now that I know Jesus, I boast in my weakness./ Because if grace is water, then the Church should be an ocean/ it’s not a museum for good people, it’s a hospital for the broken.”

Mostly what Bethke seems to be riffing on is the difference between law and grace–righteousness by faith and not by works. This is a classic tenet of Pauline Christianity, and really the theological backbone of Protestantism. In other words, Bethke is not just following Jesus, but a 21st century perception of a Pauline interpretation of Jesus. (There’s a written quote from Romans 4:5 at the end.) You can’t get from Jesus the man from Nazareth to Jesus the Christ and only Son of God, much less the Protestant conception of justification by grace through faith, without going through two millennia of church tradition, readings and re-readings of scripture, and theology. In other words: religion.

What makes this even more puzzling is Bethke is a member of Mars Hill Church in Seattle. This is a rapidly growing megachurch that wraps its highly dogmatic, patriarchal, fundamentalist Calvinism in a media-savvy package. But I guess it’s not religion when the pastor wears a T-shirt and a wallet chain.

“What if I told you Jesus came to abolish religion?/ What if I told you voting Republican wasn’t really his mission?/ What if I told you ‘Republican’ doesn’t automatically mean ‘Christian?’”

Bethke’s video gets at one of the fundamental problems churches have today, which is reaching out to a generation that often describes itself as “spiritual but not religious.” After three decades of American Christianity – both Protestant and Catholic–being used as a proxy for the Republican Party, people of the younger generation are highly (and rightly) skeptical of religion. To his credit, Bethke mentions this in his poem. In other interviews, he suggests his generation has the perception that being a Christian means “hates gays, can’t drink beer, no tattoos.” Again, how this lines up with his church’s teaching is puzzling. Mars Hill pastor Mark Driscoll definitely seems to like beer and tattoos, but hates gays.

This is the primary complaint I have with how evangelicals appropriate popular culture for religious aims. Pop culture is cool, it sells, it packs the kids in, and evangelicals have been brilliant at manipulating it at least since the Jesus People movement of the 60’s. They’re fine with using the elements of popular culture—rock music, tattoos, spoken word—as long as it’s drained of its substance. But nothing of substance changes about their theology. It’s still the same old substitutionary/juridical atonement—Jesus died for you and your personal salvation; God required a human sacrifice to atone for your sin. Many of us have ethical problems with this theology. And it’s quite possible that the myopic, salvation-centered but justice-averse theology of both right-wing political Christians and Mars Hill Church is a result of this conception of the Gospel.

I must admit though, I’m jealous. (Jesus didn’t say it, but my religious tradition of Christianity tells me that’s one of the seven deadly sins.) I wish progressive Protestants could come up with something as cool as this, and perform it as passionately as Bethke.

I have this idea that maybe what could reach this generation is not a newer, hipper version of the old time religion of sin and atonement, but a theology of incarnation, oneness with the oppressed, personal and community reconciliation, and the celebration of our status as co-creators with God. I wonder if what people have really had enough of is a theology in which guilt and shame are the necessary precursors to salvation. It’s not that we shouldn’t acknowledge our faults, our baggage, our “sin,” if you will, but our motivation to do this should be to live into a more joyful awareness of our being created in the Image of God.

To be honest, though, I don’t know if this generation even wants theology, and they seem fundamentally confused as to what religion actually is. Typical X-er or Millennial: “I’m spiritual but not religious, and yet every summer I go to a festival in the desert where I dance naked around a giant burning statue. Wouldn’t want to have anything to do with religion, though.”

Yet I continue to hold out the hope that if progressive Protestantism were to dialogue with popular culture—not appropriate, but dialogue—we might be able to engage this generation on its own terms. Because with all due respect to Bethke’s sincerity and heartfelt belief, his “non-religion” is just going to lead people back to dogmatism and judgment.