“I’ve come to the conclusion that there are really only two types of people in San Francisco…’Jeanettes’…and ‘Tonys.’ Jeanettes are people who think that the city’s theme song is ‘San Francisco’ as sung by Jeanette MacDonald. Tonys think it’s Tony Bennett singing ‘I Left My Heart in San Francisco.’ Everyone falls into one camp or another . . . in a manner of speaking.” — Michael Tolliver in Armistead Maupin’s Further Tales of the City.

For the last two weeks I have felt what the Israelites must have felt returning from Babylon. Coming back from the far provinces to the Bay Area has sometimes left me bleary-eyed with disbelief, wondering if I’ll awake from the dream of the high-tech metropolis and find myself back in the swamps of South Louisiana.

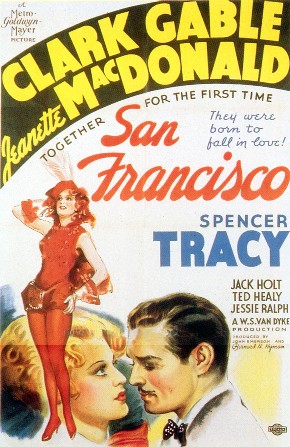

So just to stop pinching myself and get back into the spirit of what locals call The City, I’ve been watching a series of San Francisco classics on film. Being a “Jeanette,” I thought I should start with San Francisco, the 1936 Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, and Jeanette MacDonald film that introduced the city’s bouncier, campier theme song. (San Francisco, open your Golden Gate/You’ll let no stranger wait outside your door…)

The story is set in the Barbary Coast—the saloons, brothels, and burlesque theaters that sprung up in the late 19th and early 20th centuries north of Market Street along the Embarcadero, some of it literally built on the carcasses of Gold Rush ships abandoned in harbor.

Clark Gable plays his usual charming cad character, this time as Blackie Norton, king of the Coast and owner of the Paradise Club. His best friend is Father Tim Mullen (Spencer Tracy) a childhood pal who runs a nearby mission for the poor, and still hopes for redemption for Norton. In walks Mary Blake (Jeanette MacDonald), a classically trained singer who’s down on her luck. Blackie offers her a job, but only if she’ll jazz up her act for his theater. Father Mullen sees Mary, still uncorrupted by the bawdy excesses of the Coast, as the key to winning Blackie’s soul.

MacDonald, though beautiful and with obvious vocal talent, grates with her passive Sunday school-girl act. Her heart doesn’t seem to lurch back and forth between the devil Gable and the angel Tracy so much as the two men seem to pull at her in their spiritual tug-of-war. It’s like she doesn’t have a thought in her head except to keep singing. Which she does. Endlessly. When she’s not “jazzing up” the theme song to San Francisco, which is indistinguishable from when she sings it “straight,” she’s performing in the local opera house. The difference between the “high art” of the opera house, and the “low art” of the burlesque theater acts as a metaphor for the polish of civilization wiping away the tarnish of a frontier town. But after Jeanette’s long, looooong, operatic scenes from Faust and La Traviata, we’re ready to go back and see what the can-can girls are up to at the Paradise Club.

Gable is at the height of his powers as a predatory womanizer. “Well sister, what’s your racket?” he asks Mary when she first shows up. “I’m a singer,” she says. “Let’s see your legs!” he says. “I’m a singer!” she insists.

Blackie calls everyone who’s not as smarmily seductive as he is, “suckers.” My favorite use of this term of art is when Blackie tries to enforce his contract on Mary’s performances by bringing in a kind of a legal thug called a “process server.”

“That process server is the meanest man west of the Rocky Mountains. He’d push his mother off a ferryboat for half a dollar. Yeah, he’d turn the air off in a baby’s incubator just to watch the little sucker squirm.”

The city’s resonance with Blackie is obvious when Father Tim calls San Francisco, “The wickedest, most corrupt city, most Godless city in America. Sometimes it frightens me.”

But this was the early days of the Hays Code, and no debauched Hollywood production would be complete without some “compensating moral values.” That is, Divine Vengeance opening up a can of whoop-ass on the sinners so they’ll feel some real pain for their evil. Fortunately, God provided the scriptwriters the 1906 earthquake.

Once the shaking starts, the film transforms from a musical-dramedy to a full-on disaster film. And it doesn’t pull any punches. The scenes of the earthquake and its aftermath are spectacular. No jiggling cameras here, MGM built the set to shake and fall apart as central casting went screaming for the doors. The scenes of destruction are not stock footage of buildings coming down, but elaborate models of famous buildings like old San Francisco City Hall crumbling to pieces. As the denizens of the Barbary Coast wander about in realistic states of shock, a vertical fault rises in the middle of the street and underground natural gas lines ignite shooting flame into the air. Soon the whole model city is burning, and the Barbary Coast is turned to ash. This is early Hollywood special effects at its best.

Gable spends the next day and night wandering from relief camp to relief camp looking for Mary. When he finally finds her, she’s singing of course, dewy makeup unblemished, leading a bedraggled choir in “Nearer My God to Thee” as an extra expires. Gable finds himself wanting to kneel in thanks to God, and his priest friend is there to encourage him. God has wiped the sin from the city and from Blackie in on fell swoop. Too bad all those other people had to die in the process.

The film ends on a high note, with the people of San Francisco promising to rebuild, looking over the destroyed city and singing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which transitions into the San Francisco theme song at the end. In the original ending shown in theaters (unfortunately not on the DVD or streaming versions) there were shots of the Golden Gate Bridge being built, which would open the next year. It must have been inspiring to Depression-era audiences to see such a tangible sign of progress rising above a city that was once in ashes.

What resonated for me was the second part of the song’s chorus, the part that goes, “San Francisco, here is your wandering one/Saying I’ll wander no more.” For all her camp Sunday-school sincerity, I’m definitely a Jeanette. And I’m planning on “Wandering no more.”

Perhaps part of the reason for the camp aura that surrounds MacDonald in the movie San Francisco, and the song “San Francisco,” is Judy Garland’s indelible performance, which embellishes on both. Click on the picture to watch the video on YouTube.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sSr47vIUz94[/youtube]