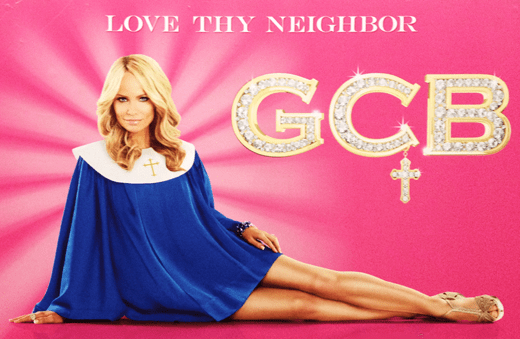

Richard here with my first post-dissertation post. GCB is the warped new soap/comedy on ABC, following Desperate Housewives on Sunday nights, and it’s more about hurt and memory than religion and hypocrisy.

Teenage Girl: “Mama, all the other girls are getting starter boobs.”

Mother: “Well, Christmas is comin’, honey!”

Church sign: “YOU REAP WHAT YOU SOW”

Boy: “What does that mean, Mom?”

Mother: “That’s Texan for Karma.”

“Hell hath no fury like a bunch of women you were mean to in high school.”

GCB (aka “Good Christian Belles” or “Good Christian Bitches,” depending on who’s doing the P.R.) is the warped new soap/comedy on ABC, following Desperate Housewives on Sunday nights. Produced by Darren Starr, creator of Sex and the City, and written by Robert Harling, author of Steel Magnolias, you just knew this was going to be the most quotable series on television. There are a dozen more priceless one-liners from this show in addition to the ones above, and there have only been two episodes broadcast so far.

The series begins when a mother of two kids, Amanda Vaughn (Leslie Bibb), is compelled to leave California and come back to her mother’s home in Dallas after her husband dies in an embarrassing accident involving a mistress and money stolen in a Ponzi scheme. Amanda’s mother, Gigi, (Annie Potts) is a true Lone Star lady, living in an air-conditioned mansion with guard dogs named Tony and Romo (after the Cowboys’ quarterback, of course) an unlimited credit line at Nieman Marcus, and a biting tongue for criticism of her only daughter.

Literally peering through the hedges in the house next door is Carlene Cockburn (Kristin Chenowith) a former ugly duckling, now transformed into a vicious swan, thanks to plastic surgery. Carlene was one of several girls, including Cricket Caruth-Reilly (Miriam Shor), Sharon Peacham (Jennifer Aspen), and Heather Cruz (Marisol Nichols) that Amanda was cruel to in high school. Besides tormenting the then-ugly Carlene, Amanda destroyed Sharon’s chances of winning Miss Teen Dallas by telling the judges the beauty queen wasn’t a virgin, and spread the rumor that Cricket had herpes. The lucky few that fit into Amanda’s inner circle were known as “the foxes” and the ones who we re victims of her ire she labeled “javelinas,” after a species of wild Mexican pig.

Amanda comes to regret her meanness as an adult (she’s shocked to find out from her daughter that the “foxes” and “javelinas” labels still exist at her old high school). The girls Amanda tormented, however, have now formed a claque of rich and successful socialites, are not in the mood to let bygones be bygones. This is especially ironic since all are steadfast churchgoers and consider themselves to be holy and pious Christians. When Amanda gets dragged along to church by her mother, she finds herself confronted by the whole gaggle of spurned women, wielding Bibles and out for blood.

This leads to all kinds of entertainingly anti-Christian behavior. Charlene takes to using her position as the star singer in the church choir to call out the “wayward” Amanda as a fallen woman during congregational prayer. She later dedicates a song to Amanda, “Jesus Take the Wheel,” an especially underhanded choice since Amanda’s husband died in a car accident. There’s little Carlene can’t justify by using her faith, including dressing as a sexpot. Referring to her prominently displayed breasts, she rationalizes, “Cleavage helps your cross hang straight,” and, “I have a wonderful spiritual husband who likes ’em where he can see ’em.”

Amanda soon learns the techniques for countering the hypocritical Christian crowd. Cornered by the mean girls after church, who unsubtly suggest she needs to get her life together (and maybe leave town) Amanda tells Carlene, “I can do all things in Christ, who strengthens me” (Philippians 4:13), and adds a “God bless y’all.” “Well, well, well, Carlene,” Cricket says, shocked, “I think she just out-Christianed you.”

There are a lot of groups that could be offended by this show: conservative Christians, Texans, women. Pro-Puritan lobbying groups like the Culture and Media Institute and the Parents Television Council immediately got their flacks out to decry the show as “a sex-filled attack on Christians.” The show makes fun of hypocrisy, not Christianity. If these groups ever figured out irony, they’d be out of a job.

As far as Texans are concerned, I think they pretty much revel in their idiosyncrasies: big trucks, big hair, nominally Christian but ready to throw down when social standing or politics are at stake. Take a look at Rick Perry and tell me he’s not as vain and catty as any of the women in this show. Let’s face it, Texas, you’re crazy and heavily armed and you scare us. We make fun to hide the fear.

In their carefully-staged outrage, the Parents Television Council also mentioned that the word “bitch” was offensive to women. I don’t believe for a minute they actually care about the position of women in society, but they do have a point. The only pang I feel in watching this guilty pleasure is in its treatment of women. When do we get past the idea that for a woman to get ahead, she has to push her breasts together, fluff her hair, and set her lipstick on “kill”?

Feminist scholar Stephanie Coontz has pointed out the strange place that women and girls have gotten to in our culture where they are told they can do anything with their lives—run a company, run for President, be a doctor, a lawyer, an astronaut—anything—as long as they stay “hot.” Just to get by in modern America, women and girls have to be equal parts The Feminine Mystique, and Sex and the Single Girl.

The show continues a few of these stereotypes well beyond what’s necessary for the comedy. The Sharon Peacham character, as an insecure ex-beauty queen, is constantly stuffing something into her mouth. “Ha-ha,” we’re supposed to laugh, “she can’t stop eating, she’s fat.” Except she’s not. The actor who plays her, Jennifer Aspen, is the only younger woman on the show with a normal body size, especially compared to her skeletal costars Bibb and Chenowith.

But just as I’m tempted to get my feminist knickers in a twist, I think about my favorite Texan GCB, the state’s late former Governor Ann Richards—no wilting flower, she. I think she would have found this show a hoot. I once heard this accomplished woman tell an audience on an NPR broadcast that she and other Texas women tease their hair bigger as a means of balancing out the size of their butts.

What’s most surprising about GCB is how gay the show is. I don’t mean the gay subplot (and of course there is one); I mean the jaundiced camp humor and drag queen-like characters. I will forever remember the sheer twistedness of the image from the second episode of Carlene tearing off in her two-seater convertible Audi with a roast pig in the passenger seat as she abandons Amanda at a barbeque pit eighty-plus miles outside of Dallas.

It makes me wonder how we got to this place where camp, which was once a secret code for an oppressed minority, has become mainstream humor. At some point there was Will and Grace, where straights were introduced to gay humor in a gay context. But then Desperate Housewives and Project Runway and Glee came along, and the camp was here to stay even though the gays were only a portion of the show. And regular people–and by regular people I mean normal people who don’t live in California or New York City—are in on the joke.

GCB isn’t so a much a parody of Christianity or the South as it is gay men’s parody of straight people, particularly straight girls and women. Most gay men would have loved to fight out their popularity on the open field of battle in high school. To be a popular girl, or a smart but pretty girl who could hold her own against the popular girls, was their utmost fantasy. For many of them, the Machiavellian machinations of the mean girl set were their secret soap opera, as thrilling as anything on Dynasty.

The reality was many gay boys in high school—especially before the days of “It Gets Better” and “Born this Way”—just had to keep their heads down and try not to get pounded. They (and by they I mean we) only dared to sparkle for brief moments in the theater club, chorus or band, where they could try on different personas and emotions and be the drama queens they knew themselves to be.

The show is about the memory of what it was like to be awkward and out of place in high school, what it means to look back at the lost kids we were as the adults we are now, and how some scars don’t totally heal. Somehow the ache is still there, and if you dwell on it long enough, the perverse humor of a show like GCB bubbles into consciousness, releasing itself in peals of maniacal laughter. Because if you don’t laugh, you’ll cry.