I was in a gay bar in New Haven, Connecticut when I realized George Michael’s “Freedom ’90” was a coming out song. Of course I knew the singer was gay after a cottaging incident in L.A. in 1998. But somehow, being in The Garage on a Tuesday night, on the hunt for the first time after I had split up with my boyfriend of four years, the song’s samba beat clicked with my gay gene, causing me to get my seminary student swerve on while sipping a Manhattan. Maybe it was the song’s persistent bongo drums, or the setting, or the drink, but I noticed the words for the first time: “I think there’s something you should know/ I think it’s time I stopped the show/ There’s something deep inside of me/ There’s someone I forgot to be…” Really, George? Who is it you forgot to be?

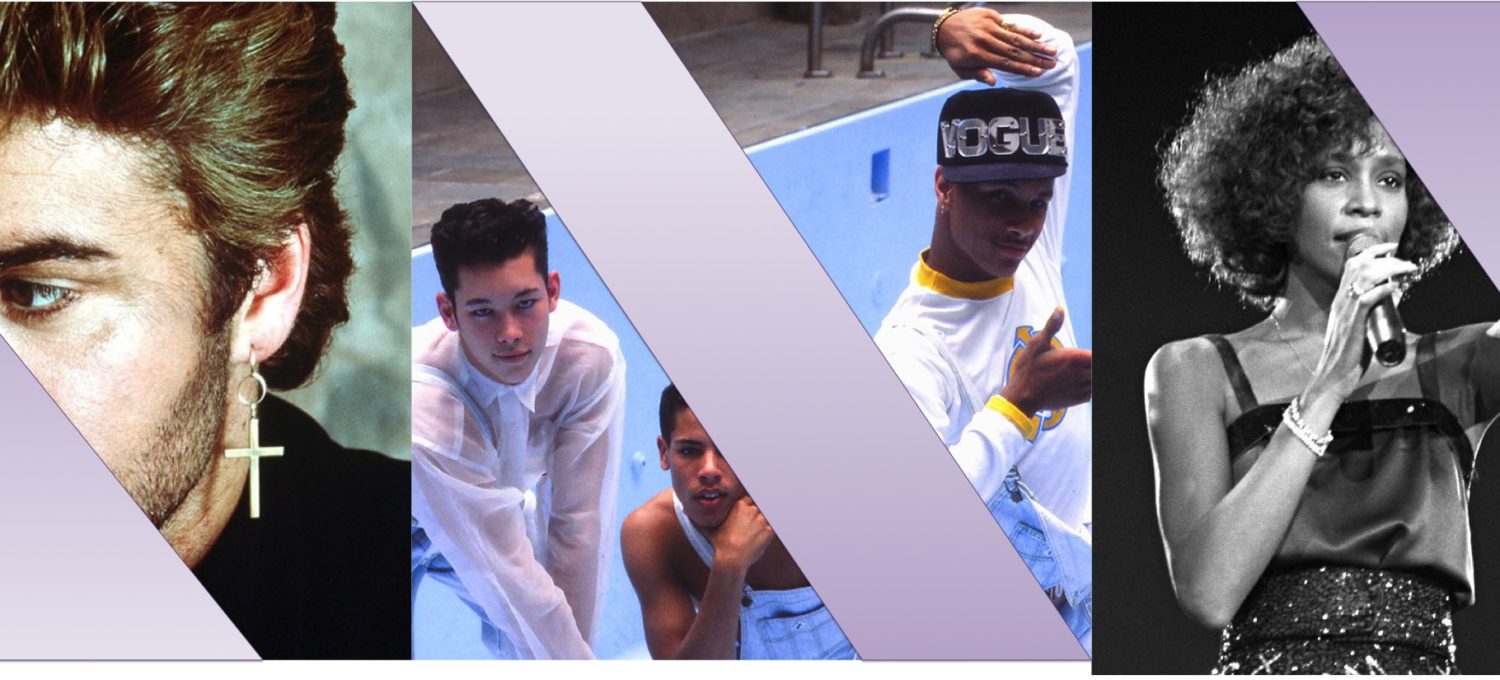

It’s amazing how closeted artists are able to communicate with their queer fans through their songs and videos. A trio of streaming documentaries has let us in on some of the backstage stories of pop stars of the 80s and 90s who were less than fully “out” at the time, but somehow managed to accumulate huge followings with the gays anyway. Two of the films, Strike a Pose (Netflix), which tells the story of Madonna’s dancers in her legendary 1990 Blonde Ambition Tour, and Freedom: George Michael (Showtime) are retrospective, post-closet histories. But Whitney: Can I Be Me? (Showtime) is an active “outing,” discussing Whitney Houston’s bisexuality openly for the first time.

Freedom: George Michael

There are lots of things I learned from the film Freedom, which was actually an autobiographical project George Michael was working on when he died. I didn’t know “Freedom ’90’s” album Listen Without Prejudice, Vol. 1 was a bigger seller than Michael’s first solo album Faith. Because of a contract dispute with Sony, they basically didn’t promote the album in the U.S. at all. Unfortunately, for many Americans, George Michael will be remembered as something of a one-album wonder, with a smash video for the song “Faith” with the singer dressed in tight jeans, a biker jacket, and aviator sunglasses doing Elvis hip swivels against a classic jukebox (speaking of communicating with a gay audience). But he continued to chart hits and albums in the UK through 2012.

I didn’t know George Michael had lost his lover, Anselmo Feleppa, to AIDS in 1993, and shortly after that, he lost his mother to cancer. Little wonder that Michael reveals in the film that he felt God was “picking on” him. It may also explain some of his difficulties with drugs and alcohol, which are not discussed in the film. The documentary was obviously a legacy-building piece. But you don’t get liver cirrhosis—one of Michael’s causes of death—by bingeing on Diet Coke.

I didn’t know George Michael had so much success as an R&B artist. Faith actually won two American Music Awards in 1989 for Favorite Soul/R&B album and Favorite Soul/R&B Male artist, which caused some R&B artists to express consternation at the time. Since then, many R&B musicians have embraced Michael’s music as part of the canon, with covers of his songs performed by LL Cool J, Mariah Carey, Gloria Gaynor, and Brian McKnight. Debarge sang “Careless Whisper” to memorialize George Michael at the BET Awards last summer. Which is to say George Michael may not have been so much appropriating as participating in the kind of collaboration and reinterpreting of genres that adds to the creative mix of popular culture. Another way of saying it is, Some people just have soul.

Strike a Pose

My love affair with Madonna began in a frat house. During the mid-nineties, while staying at my college music fraternity’s headquarters, our chapter found ourselves watching a VHS of Truth or Dare, the backstage documentary of Madonna’s Blonde Ambition tour. This was the movie where Madonna demonstrated oral sex technique on a water bottle and two of the male dancers shared a passionate kiss. My chapter brothers justified their interest in this queer entertainment by continually exclaiming about Madonna’s fantastic knockers. But I was mesmerized by something completely different: her gaggle of unapologetically flamboyant gay dancers. They seemed to form a fierce family, with Madonna playing Mother Superior. I couldn’t get the movie out of my head for days—it made me want to drop out of college and go join the tour as a backup dancer, just to experience such a tightly-bonded community of gay men.

Strike a Pose catches up with most of the members of the dance troupe—Luis, Jose, Oliver, Salim, Kevin, and Carlton—and brings them together in a reunion twenty-five years after the tour. We already know from Madonna’s original documentary that except for Oliver Crumes, who was hired as a self-taught “street dancer,” all the other dancers were gay. Luis Camacho and Jose Gutierrez were even part of the House of Xtravaganza, one of the “families” of vogue dancers and drag performers in the legendary documentary Paris is Burning.

The big revelation in Strike a Pose is that several of the dancers have been living with HIV since the 90s. Salim Gauwloos and Carlton Wilborn knew about their positive status during the Blonde Ambition tour, but were petrified to talk to anyone about the disease. At the time, there was still open discrimination and social stigma against people living with HIV/AIDS, this dread disease that was a “death sentence” before protease inhibitors. In fact, the only dancer not to join in the reunion in Strike a Pose was the achingly beautiful San Franciscan, Gabriel Trupin, who died of AIDS at the age of 26 in 1995.

Strike a Pose is an entertaining “Where are they now?” Most of the dancers have gone on to success in other shows and as teachers and choreographers—some of them working with other big names like Beyonce, Katie Perry, and Lady Gaga. The reunion is touching and shows the bonds of family between these dancers hasn’t faded, even as hair has grayed and joints have stiffened. Oliver still seems like he was in Truth or Dare, the odd man out, making awkward comments at the wrong times.

Some of the dancers still have relationships with Madonna, but others had a falling out with her. Kevin Stea, Gabriel, and Oliver sued her after the tour because they were not compensated for their roles in Truth or Dare. It’s hard to believe in these days of reality television that there could be cameras everywhere and people wouldn’t be aware the footage would end up on screen. But it’s highly believable that Madonna would enlist those around her to create something that would ultimately make her a lot of money without letting the others know or giving them a cut.

Still, I was moved to see these dancers together again telling their stories. It confirmed for me that I wasn’t alone in seeing that film as a significant pop culture moment, particularly for its unabashed gay visibility. The dancers say they still receive e-mails and letters from fans telling them how much Truth or Dare meant to them. And although I know I’m not the twentysomething with boundless energy I was then, and Madonna herself is close to qualifying for Social Security, I still dream of mastering my vogueing technique and joining her tour as a dancer.

Whitney: Can I Be Me?

I don’t have a great gay story about my introduction to Whitney Houston. There was a teacher in my gifted program in elementary school that played “The Greatest Love of All” as a soundtrack to our end-of-year slideshow. Maybe the fact that I can still remember what song my teacher played to a fifth-grade slideshow—and how it added fabulously to the production values—is all the gayness that story needs.

Can I Be Me is by far the most tragic of the three documentaries. It begins by showing Whitney as a teenager singing in her church in New Jersey. When she released her first album at age twenty-one, she was marketed as a squeaky-clean pop princess. This persona was the creation of her gospel-singer mother, Cissy. It seems inevitable that someone under that much pressure to be pure would end up with a bad boy (and bad influence) like Bobby Brown. Brown was one of the major enablers of Whitney’s use of drugs and alcohol.

According to the documentary, the balancing influence in her life was her childhood friend and longtime manager Robyn Crawford. Many friends have reported that Robyn was a romantic partner as well, which did not sit well with Whitney’s Baptist family. The family and Brown were forever trying to separate Whitney and Robyn. Eventually, they succeeded, pushing her out after a particularly grueling world tour in 1999.

The third act of the documentary shows Whitney’s downward spiral. One particularly horrible moment was in 2000, when Whitney was supposed to sing at the Academy Awards, but couldn’t focus during rehearsal, and was fired by music director Burt Bacharach. The song she was supposed to sing was “Over the Rainbow.” How Judy Garland-appropriate, and likely to add to her memorial cult among gay men. What is it with us gays and our drugged-out divas?

The story only gets worse from there, ending in Houston’s death, and later the death of her daughter, Bobbi Kristina. Bobby Brown later said had Robyn Crawford still been in Whitney’s life, she would not have died of the drug overdose/drowning in 2012.

I’ve never been a huge Whitney fan. All of her songs, even her ballads, seem to end inevitably in technical fireworks. I couldn’t stand the sheer vocal jingoism of her “Star Spangled Banner” rendition, which seemed to be on autoplay on the nation’s radios during the Gulf War and after 9/11.

But this documentary helped me understand and appreciate Whitney the performer, the artist, the person. The girl blessed with a Stradivarius of a voice, who could make it zip and soar and growl at her whim. And the girl cursed with a family who latched onto that voice as a means to their own wealth and success…and insisted she do it on their terms. If Whitney’s perpetual question was “Can I be me?” the answer was always, “No.”