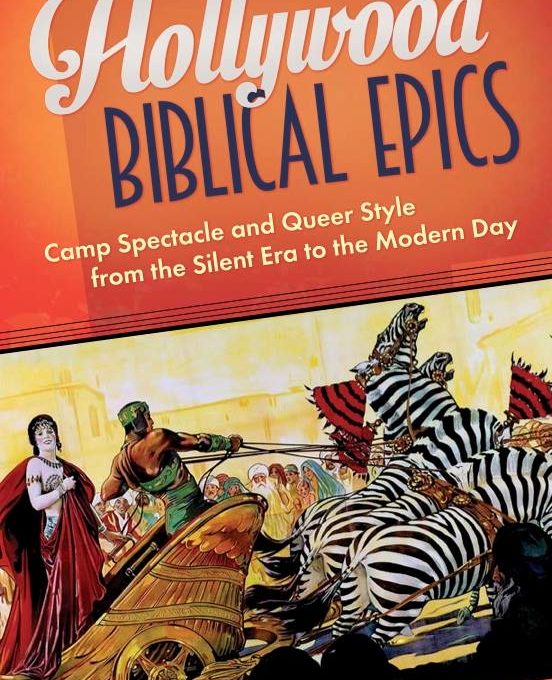

So the big day has arrived. My book, Hollywood Biblical Epics: Camp Spectacle and Queer Style from the Silent Era to the Modern Day, drops today. Get it on Amazon or anywhere fine books are sold….online. With a title like that they’re not exactly going to have it at your local Books-A-Million.

So the big day has arrived. My book, Hollywood Biblical Epics: Camp Spectacle and Queer Style from the Silent Era to the Modern Day, drops today. Get it on Amazon or anywhere fine books are sold….online. With a title like that they’re not exactly going to have it at your local Books-A-Million.

To celebrate, I want to post an excerpt and a link to a recent appearance I made on the “Popping Collars” podcast explaining some of what the book is about and my interest in popular culture and biblical epics.

“Popping Collars” was started by two of my former students, the (now) Reverends Greg Knight and Betsy Gonzalez. They were part of the first class of “Pop Goes Religion: Religion and Popular Culture” at Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley when I was a doctoral student there. It’s really rewarding when you see what your former students are up to, and especially rewarding when you discover they’re making podcasts about the theological significance of Mad Men.

Here’s the link to the whole podcast, which is much more entertaining than reading a transcript.

Here’s a not-at-all accurate transcript, so listen to the podcast if you want to hear what we really said.

This is Part I — I’ll post Part II later this week.

Popping Collars Podcast #20: “Once More with Passion”

Betsy Gonzalez and Greg Knight: So tell us where you interest in combining popular culture and religion came from.

Richard Lindsay: Some of this came from my natural interest in popular culture and that I’m always looking for ways to make faith more relevant. I come from a Presbyterian background. I love the Presbyterians—they’re my family of origin. They’ve given me a strong grounding in scripture and theology. But one of the things they don’t always do well at least in the more moderate to liberal churches is address (popular) culture. At times they hold their scriptural interpretation and theology aloof from culture. And I think it’s a reason for mainline church decline. I think we’ve kind of left culture to the evangelicals. We’ve kind of said to the evangelicals you all can deal with popular culture we don’t want to dirty our hands with that.

Some of the neo-orthodox theology that reigns in the Presbyterian Church really doesn’t have a lot of use for culture. It’s kind of like, “We are really about the Kingdom of God and the only revelation we can derive is from Scripture.”

And yet I find myself all the time finding revelation–and even divine revelation–in popular culture. I find myself watching films or listening to songs and it feels like God talks to me through those things. And this isn’t in the way that “Helter-Skelter” talked to Charles Manson or anything like that. I actually feel something coming from those different sources.

Greg Knight: Yeah, I remember in one of the early classes, you brought up Harry Potter and you were like, “We can’t just have conversations where the Catholic Church comes out and says there’s no value here. Don’t watch Harry Potter just ignore it.“

A lot of people set up these false dichotomies like science versus religion or popular culture versus religion. It’s got to be a conversation otherwise you’re losing the touch points that people have. Popular culture is a huge touchstone for people to gravitate towards. It’s a common language.

Betsy Gonzalez: I was super happy when U2 got brought up early, when I knew that we’re hitting that first or second class and we’re going deeper and wider. That’s when I was like, “This is excellent.”

It’s this ability to train my radar to really start to see all the different ways that faith and culture were intertwined together. Because I’m taking all the seminary classes and I’m actually bringing them into this great love of culture and we can actually have them talk back and forth.

I love that you have taken a real homiletical edge with it as well. That’s a great place to bring things into the conversation, and that’s where I find I pull on it the most. That and teaching high school kids. It just helps make it alive because culture moves fast.

Richard Lindsay: My whole thing in terms of teaching the course was rather than seeing the Church or religion as being in a higher place and popular culture in a lower place, I thought, “Let’s even that out so religion in popular culture can have a conversation on equal ground.”

And then let’s even take it even a step further and say that there may be times when popular culture speaks to issues of faith or spirituality better than traditional religion does. And we need to listen for those moments as well. We need to listen for those moments when the flow is reversed and popular culture can teach us something new about our faith.

We transition to talking about biblical epics…

Greg Knight: I remember from the class some of the depictions of the Bible movies. We got to see the great clip of the drunk John Wayne up on the hill delivering the centurion’s lines.

Richard Lindsay: Yes, from The Greatest Story Ever Told.

(Note: In the 1965 biblical epic The Greatest Story Ever Told, John Wayne plays the centurion who stands under the cross and drawls, “Surely this man was the Son of God.”)

Greg Knight: The thing that blew my mind was the camp elements in The Passion of the Christ. I always thought [The Passion] was just a straight-up horror movie, like something Cronenberg would’ve done. But when you brought up the camp elements of the Herod scene I was like, “Wait, you’re right! There is a tie to all of these crazy Ten Commandments-type films.” There’s this thread of camp that kind of runs through there. I was hoping you could explain for us what makes something camp.

Richard Lindsay: Camp is a difficult term to define. There was a famous essay by Susan Sontag in the 1960s that talked about camp [Notes on ‘Camp’] Camp is something that is over the top that is exorbitant, but in a very ironic kind of way.

Sontag just kind of lists all these things that she considers to be camp and it’s everything from horror movies to the Palace at Versailles to everything Oscar Wilde ever wrote. She talks about it as having “A private, zany experience of the world.” She was proposing it as kind of a middle rung between low art and high art.

Greg Knight: Is it necessary for camp to be self-realized? Can you accidentally fall into camp?

Richard Lindsay: Oh yes, you can accidentally fall into camp and actually what Susan Sontag said is that’s the more rewarding camp—when somebody is camp and they don’t know it.

What I would say is that a lot of the biblical epics are unintentional camp. They have this bizarre, over-the-top theatricality. They have this bizarre mix of sex and violence and piety—so the camp is unintentional.

More discussion of camp in biblical epics. We then begin discussing how influential biblical films are in shaping our notions of scripture.

Betsy Gonzalez: We don’t realize it until we start talking about this how much we have structured our experiences of Scripture through these biblical epics. Especially these movies that are on every year at Passover/Easter, and you start reading Scripture through the visuals, especially if you’re a visual person.

Richard Lindsay: When you have visual versus text and you’re a visual person the visual is always going to supersede the text. The visual is going to stick inside your head a lot more clearly, especially if it’s spectacle. And these films are spectacle all over the place.

Then you get to the point where you can’t really tell the difference. Is that something I saw in a Cecil B. DeMille film or something I heard at Sunday school or something I actually read in the Bible? Some people see that as a great tragedy and they say we shouldn’t make these films or we shouldn’t watch these films because they’re just going to screw with our attempts at understanding the Bible. I think you should just go with it. As far as I’m concerned Moses looked like Charlton Heston. I can’t get that out of my head and why should I bother?