If one stores a collection of images of a particular literary figure, or setting, or style of costume, that collection is not stored mentally in chronological order. It does not matter whether I have seen Rita Hayworth’s Salome before viewing Gustave Moreau’s painting or after reading the version in the Gospel of Mark. All the representations collide and coalesce in my construction of the figure of Salome. In our postmodern image culture, readers are also spectators. — Alice Bach*

If one stores a collection of images of a particular literary figure, or setting, or style of costume, that collection is not stored mentally in chronological order. It does not matter whether I have seen Rita Hayworth’s Salome before viewing Gustave Moreau’s painting or after reading the version in the Gospel of Mark. All the representations collide and coalesce in my construction of the figure of Salome. In our postmodern image culture, readers are also spectators. — Alice Bach*

This is one of the central quotes supporting my dissertation, which I’m working with Praeger to publish this spring. Biblical scholar Alice Bach’s point is that with so many images, interpretations, and representations of the Bible available to us in a multimedia culture—from film to television to “Bible-Zines”, Internet preachers and podcasts—it’s often difficult to remember where we got the Biblical narratives in our heads. There’s the written Bible on the page, and then there’s the “Head Bible” we carry around with us at all times.

I’ve become increasingly fascinated with the “Head Bible,” which for many of us may be a combination of actual Bible readings, sermons, half-correct teachings from fifth-grade Sunday School teachers, Cecil B. DeMille, and the lyrics from Jesus Christ Superstar.

During recent holiday family time, I was compelled by my brother, Rob, who enjoys collecting and watching obscure and forgotten Hollywood films, to watch a biblical turkey called The Silver Chalice. This 1954 film was the first starring role for Paul Newman, and he came to regret it so deeply that he once took out an ad encouraging people not to watch it when it showed on television.

The only thing to recommend about the movie is its unconventional set design, which is a spare and modernist evocation of the Roman Empire, and an excellent score by Franz Waxman. Otherwise, it’s a lesson in tedium, with torturously wooden acting and screenwriting.

The story involves Basil (played by Newman), a young slave from Antioch who is engaged to carve a chalice in silver to encase the small bowl used by Christ in the Last Supper. His work becomes a personal struggle of faith, as he attempts to “see” the disciples and Jesus, many of whom he has never met, to carve their faces into the Chalice. Eventually he goes to Jerusalem and Rome on his quest.

In a mostly unrelated plot, Simon the Magician (Jack Palance) a minor character from the book of Acts, attempts to win the worship of the Roman people through feats of magic. His female assistant, Helena (Virginia Mayo), tries to hold back his dangerous ambitions. He is a very powerful man, and, as Helena warns in one of the more memorable bad lines of the film, “It is not for nothing that he is called Simon the Magician.” The final act for Simon’s growing following will be for him to build a tower and create the illusion of himself flying. He hopes will cause all of the Christians to start following him and stop following his rival, the Apostle Peter, who denounced him for attempting to buy the power of the Holy Spirit.

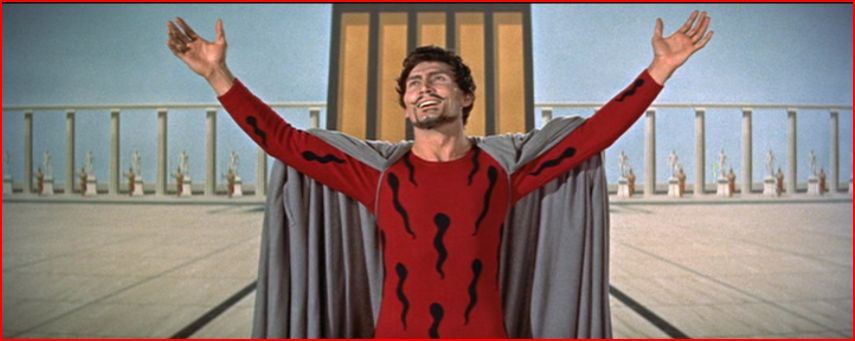

Eventually, and I’m not spoiling the ending here, because you will never feel the need to watch this film in its entirety, Simon’s hubris gets the best of him. In a (highly campy) event staged for Emperor Nero himself, Simon appears before all of Rome for his flying feat. The problem is, by this point, he has begun to believe he actually is the Messiah, and that he can really fly without the apparatus he had built to create the illusion of flying. Dressed in what could only be described as a red unitard with black sperm designs on it, he throws himself off the tower, crashing to the ground and killing himself.

What was infinitely more fascinating than the film was the family discussion surrounding it. As my brother and I were watching, my mom came in, saw Palance as Simon on the screen and said, “Oh, he throws himself off a tower, right?”

My brother Rob exclaimed, “Thanks for blowing the ending, Mom!”

My mom said, “I didn’t blow the ending, that’s what it says in the Bible.”

Now my mother is about as educated as a layperson can get in terms of scripture. A lifelong churchgoer, she has taught Bible studies at our church, and once won a national award for her grasp of Bible trivia. (There was a large traveling trophy involved; it was a source of great pride for our family.) If my mom says something is in the Bible, it’s usually in the Bible.

A quick lookup of the account of Simon the Magician (sometimes called Simon the Sorcerer or Simon Magus) in Acts 8:9-25, revealed that Simon did indeed have a confrontation with Peter, and did indeed ask to buy the powers of healing and miracles the apostles were performing. He most definitely did NOT throw himself off the tower in the Biblical story. In fact, the story ends with Peter and the apostles admonishing Simon and the magician repenting, saying, “Pray to the Lord for me so that nothing you have said may happen to me.”

That’s it. End of story. No crotch-hugging sperm suit for Simon.

Although there are early Christian traditions and some medieval legends that suggest Simon attempted to fly and was killed by his hubris, it is likely my Bible-expert mom got her memory of Simon’s fate from The Silver Chalice. Or, as Paul Newman described it, “The worst movie of the 1950’s.”

This is remarkable, because if an educated lay biblical scholar like my mom can still occasionally mix up the Bible and biblical epics, there’s little chance the rest of us won’t do the same with greater frequency. This is why I argue that, for all Christians’ claims to be knowledgeable about the Bible, what most people carry around in their brain representing the Bible is vastly different from what’s in the printed scripture. Because of this, culturally and cognitively, biblical epics could be said to be scripture—no matter how they defy biblical accuracy, or good taste.

The existence of camp in biblical films queers the whole canon of biblical narrative. It places flamboyant characters in the midst of the stately pageant of scripture and saves us from over-seriousness. I think this is a good thing. In order for the Bible or any other element of religion to be real to us, it must be so ingrained in us that it can be the subject of our daily discussions, our entertainment, or even the butt of our jokes. It must be part of the stuff of everyday life.

From now on, in my little world, in the Bible in my head, whenever I think of Simon the Magician in Acts, I’m going to think of Jack Palance in a sperm-covered unitard. That makes me very happy.

* Quote is from: Alice Bach, “’Throw Them to the Lions, Sire’: Transforming Biblical Narratives into Hollywood Spectaculars,” in “Biblical Glamour and Hollywood Glitz,” ed. Alice Bach, Semeia: an Experimental Journal for Biblical Criticism 74 (1996): 1.