Richard here. PopTheology.com benefits from the fruits of my dissertation labor. Not everything could have fit into the final draft. So here’s some background on one of the great silent epics, Fred Niblo’s 1925 film, Ben-Hur

Having just completed and defended my dissertation, my hard drive is now littered with bits and pieces of research that didn’t make the final cut of my 270-page magnum opus. One of the discoveries I made during the course of my work was that Hollywood has always had an aversion to risk-taking when it comes to new properties. Hence the current “saga-mania” (most recently The Hunger Games) that hooks viewers in for multiple films. (After the end of Deathly Hallows Part II, I calculated that I had logged 19 hours and 37 minutes of movie theater time to get through the whole Harry Potter story.)

The same is true for old properties that get revived again and again. And nothing gets revived like religious epics. I have already written about Quo Vadis, the 1951 MGM spectacular, for PopTheology. This was one of a long string of adaptations of Henryk Sienkiewicz’s beloved novel of Christian martyrs in ancient Rome. Even before 1951, there were three versions put on film without sound, a 1901 French film, and two Italian versions, one in 1913, one in 1925. Since 1951, there has been a 1985 mini-series starring Max von Sydow and a 2001 version shot in Poland. If you’re scoring at home, that’s six film productions of the novel.

Ben-Hur has had a similar string of productions, including a recent 2010 British mini-series. Of course the most famous production of Ben-Hur is the 1959 MGM film starring Charlton Heston, which has been matched but never exceeded in Oscar haul. But one that nearly measures up as spectacle and entertainment is the 1925 MGM silent production, starring Ramon Novarro as Judah Ben-Hur and Francis X. Bushman as Messala.

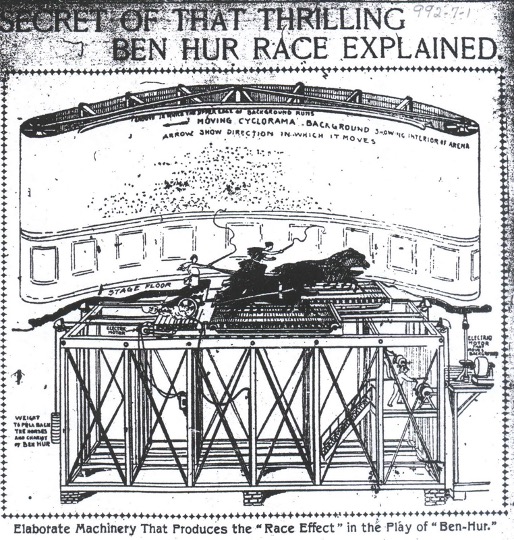

Adaptations of Civil War General Lew Wallace’s 1880 novel go back to pre-film days. Ben-Hur was first adapted as a Broadway play, produced by Marc Klaw and Abraham Erlanger, beginning in 1899. The play included a chariot race with live horses on treadmills and a massive cyclorama screen rotating in the background. It was revived subsequently many times, in the 20 years or so before films took over the place of spectacle in the theater. A live version of Ben-Hur was re-staged in 2009 in London at the Greenwich O2 Arena, involving a circus-like set and a chariot race.

In 1907, Kalem Company produced the first filmed version—a 15-minute silent version produced in New York, including a chariot race staged by the Brooklyn Fire Department on Manhattan Beach. Unfortunately, this film embroiled Kalem in one of the first film-based copyright infringement suits, since they failed to secure rights to the story from the Lew Wallace estate. (You can watch an unrestored version on YouTube without getting sued by the Lew Wallace estate.)

The 1925 version was the first major production of the newly formed Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer super-studio, and it nearly bankrupted the company right off the bat. Inherited two years into production from the Goldwyn company, the production MGM signed onto was already a mess–shooting had gone disastrously in Italy and the film was already well over budget.

The biggest calamity happened during the famous naval battle scene, which was shot using actual ships constructed in Italian shipyards. The burning oil used to create smoke effects on the wooden vessels started to catch the ships on fire, and hundreds of Italian extras dove into the water, fleeing for their lives. (This certainly adds a bit of realism to the filmed footage.) Unfortunately, this was in a time before people were regularly taught how to swim. The director, Fred Niblo, and the producers stayed mum on the details, but it’s thought that several extras may have drowned.

The film’s star, Ramon Novarro, was one of the early gay stars of Hollywood (although he could hardly have been open about his sexual orieantation back then.) A native of Mexico, he was promoted as a “Latin lover” type, set up in competition with Rudolph Valentino. Despite the presence of Novarro, however, there seems to be less gay subtext to this film than the 1959 version, which benefitted from the writing contributions of Gore Vidal.

Novarro actually looks like more of an effete young prince, unlike the strapping Charlton Heston. Francis X. Bushman, with his huge arms and massive body, is a big brute and really comes across as a lummox. Novarro’s character is no match for brawn of Bushman, and Bushman’s character seems no match for brains of Novarro.

As with many biblical epics, Ben-Hur was on the cutting edge of film technology. There are two passages filmed using an early two-strip Technicolor process: the Nativity scene and Ben-Hur’s heroic entry into Rome. The latter involved topless women strewing flowers before Ben-Hur. The lore around the film is that Niblo imported French women for these roles because he felt Italian women were too hefty. Ah, the days before the Production Code.

And it is pre-Code decadence that is perhaps the most memorable part of this film. Besides the topless women, there is full rear male nudity during the galley sequence. In one scene before the chariot race, Messala puts the moves on Iras, the most dangerous woman west of Asia Minor, and it’s strongly suggested they have sex. A galley slave is beaten to death with whips. During the naval battle with the pirates, a half-naked Roman captive is tied to the bowsprit of a ship as it rams it into a Roman galley.

The whole naval battle sequence seems to have been shot with the orders, “Okay, roll the cameras! Now, you guys beat the crap out of each other!” A ridiculous pirate named “Golthar the Horrible” impales Roman heads and holds bodies aloft on spears. As the battle rages, trapped slaves hang themselves from their chains in the hold of the ship. “A Tale of the Christ,” indeed.

The Christ story is treated in a kind of “greatest hits” fashion in Ben-Hur. The Nativity scene in the 1925 film really is a beautiful example of early color special effects. But from then on, Christ takes on a decidedly supporting role. He is always blocked from view, seen only as a sandaled foot, a glowing hand, or a shaft of light. The one interaction between Ben-Hur and Christ comes when the Ben-Hur is being driven through the desert by the Romans as part of a gang of slaves. Delicate Christ hands stop their work at carpentry and offer him a drink of water.

The light treatment of the Christ story didn’t keep reviewers from gushing over the film’s “religious” significance. As Edwin Schallert wrote in his review for the Los Angeles Times on January 3, 1926:

The march of [the events of the film] is like the oncoming of a mighty phalanx hurled without reserve or question at the one objective of victory. They are rich, lavish, and prodigal to a degree unimagined and unprecedented…Yet—all of these things pale and become naught before such a magic touch as that when a hand mystically linked with divine eternity stretches forth to extend a cup of water to the driven, crushed and beaten here as he struggles across the desert to the sea under the lash of the Romans.

Whatever. There is simply no comparison between the impact of an actor playing Christ’s hands offering a cup of water and the spectacle of nude bodies, horses and chariots charging, hacking swordplay, and spectacular costumes and sets that combine jazz age and classical paganism.

After the Italian naval scene disaster, Louie B. Mayer ordered the crew back to California to finish the film, including the chariot race. This involved building a massive Roman circus in Culver City. Much of Hollywood declared a holiday to come out and see the race, creating crowd scenes loaded with 1920s Hollywood royalty. If you look fast enough during the crowd shots, you might spot Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Harold Lloyd, John and Lionel Barrymore, Lilian and Dorothy Gish, Sid Grauman, Samuel Goldwyn, Myrna Loy, Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, and Fay Wray. $5,000 was promised to the rodeo wranglers driving the chariots for whomever won the race. There was one spectacular crash, which you can see at the end of the race, a multi-chariot pile-up. The credits should have included the disclaimer, “The Los Angeles Humane Society has confirmed that many animals were harmed in the making of this film.”

Like the 1959 version, which was an attempt to save MGM from decline as it competed with television, the 1925 version was a bet-the-house proposition. The 1925 film grossed about 4.3 million, barely squeaking by the final production cost of $3.9 million. It held the record for most expensive film ever made well into the 1940’s, even against such budget-busters as Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz. Ben-Hur was also the most expensive silent production made until last year’s The Artist, which cost $15 million. Adjusted for inflation, however, The Artist doesn’t even come close. In 2012 dollars, Ben-Hur’s cost would stand at over $50 million.

The 1925 Ben-Hur is included in the four-disc collectors edition DVD released in 2005, and in the 50th anniversary “Ultimate Collector’s Edition,” released on Blu-Ray in 2011, both by Warner Home Video. For more on the story of the 1925 Ben-Hur, see the chapter “The Heroic Fiasco” in Kevin Brownlow’s classic Hollywood history text, The Parade’s Gone By.