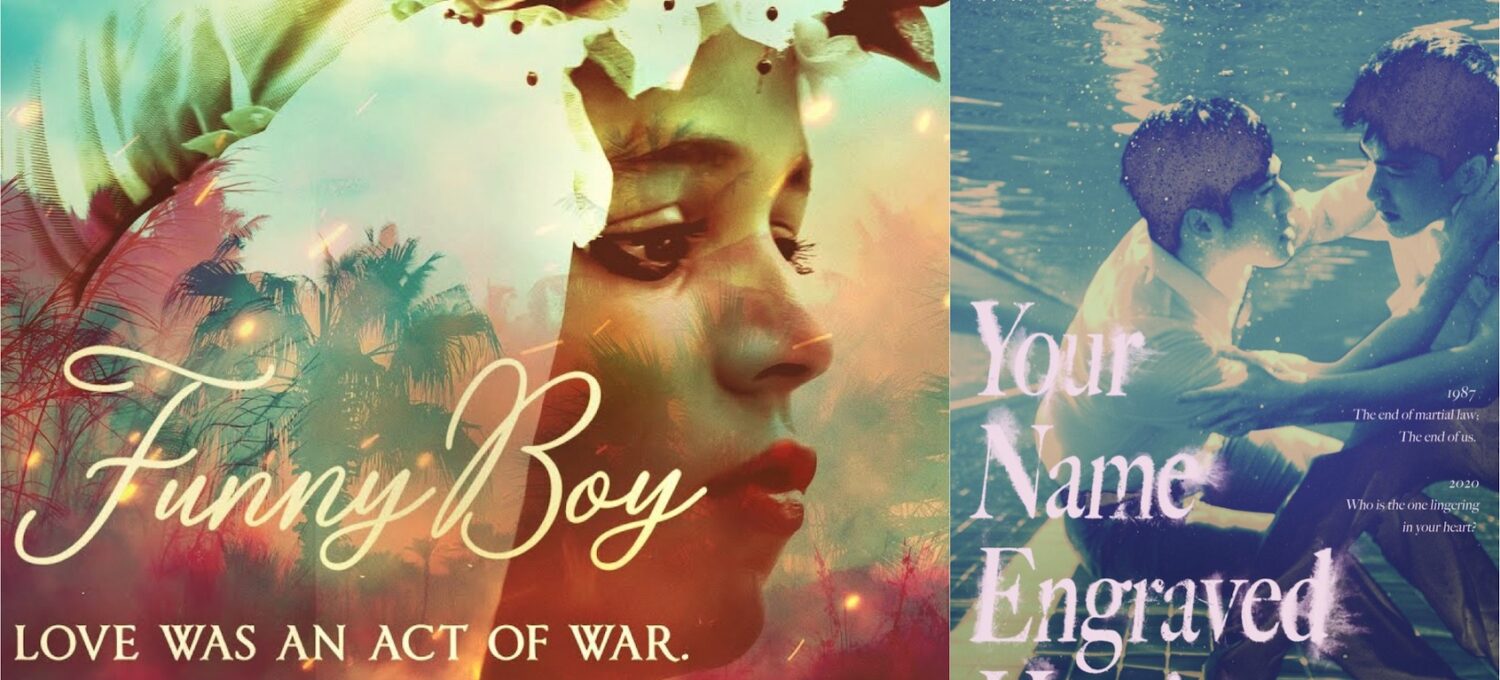

Two groundbreaking coming-out films from Asia are now available on Netflix: Your Name Engraved Herein, from Taiwan, and Funny Boy, from Sri Lanka/Canada. This is the upside of the entertainment behemoth’s vice-like control over new film releases—the possibility of greater exposure to international cinema.

Your Name Engraved Herein, directed by Patrick Liu, is the highest-grossing Taiwanese film with an LGBTQ theme. With Taiwan’s first-in-Asia legalization of same-sex marriage in 2019, the film has captured a cultural moment for the island nation.

The film takes place in 1987, when martial law was repealed in Taiwan after 38 years, opening the society to greater personal expression and political dissent. For two high school boys, the quiet A-Han (Edward Chen) and the rambunctious Birdy (Jing-Hua Tseng), the political changes are of little help as they begin to experience feelings of attraction for each other. The Catholic school they attend is strictly against all forms of teenage romance, homosexual or heterosexual. (The constant refrain, typical of many southeast Asian cultures: “Get into college first, then you can date!”) Gangs of boys in the school also mete out violent punishment to any student perceived to be gay, with tacit support from the school administration.

The relationship between A-Han and Birdy hits a snag during their senior year when the school begins to admit girls. The rebellious Birdy meets a kindred spirit in a girl, Ban-Ban (Mimi Shao), who rather daringly mouths off to the school’s headmaster when he objects to the band teacher’s mixing boys and girls in the same ensemble. Birdy begins dating Ban-Ban, and it’s unclear if A-Han has misread Birdy’s feelings for him, if Birdy is expressing bisexuality, or if Birdy is attempting to save himself from the disapproval of his schoolmates by dating a girl. Either way, A-Han is devastated as it seems his love for Birdy has been rejected.

The Catholic context doesn’t do much for the story except turning the screws a little more on A-Han’s alienation from his family and school. There is a hippy Canadian priest who acts as school chaplain, Father Oliver (Fabio Grangeon), who rolls his own cigarettes and spouts clichés like “profiter du moment” (live in the moment). He listens earnestly to A-Han as he pours out his anguish over Birdy’s hot and cold affections, but is incapable of providing the teen with any helpful advice.

The film doesn’t go very far in terms of plot, but is successful in evoking a mood. The cinematography is beautiful and gives a strong sense of place. The aura of school uniforms, emotional repression, and unrequited male crushes spirited my husband Fred back to his school days in Singapore. The filmmakers even got the soundtrack right, with Mandarin-English pop songs by 80s crooner Bobby Chen.

Part of the film’s success undoubtedly comes from the cross-cultural popularity of Japanese yaoi—comics and novels about teenage boys falling in love with each other, often written by and for young women. Both Edward Chen and Jing-Hua Tseng seem right out of a yaoi manga book, with puppydog eyes, handsome, angular faces, and lanky bodies, and oh so many emotions.

But for southeast Asian men like my husband, who grew up in the 80s and 90s, the film ticks many of the same boxes of nostalgia, romance, and longing that have made American and European coming-out films so popular.

The second film now streaming on Netflix is Funny Boy, an adaptation of the 1994 Lambda Award-winning novel of the same name by Canadian/Sri Lankan author Shyam Selvadurai. The film is directed by Deepa Mehta, who has courted controversy by focusing on women’s lives and sexuality in India, particularly in her trio of films, Fire (1996), Earth (1998), and Water (2005). The film was released by Ava Duvernay’s ARRAY distribution company.

The film begins with an eight year-old boy from a wealthy Tamil family in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Arjie Chelvaratnam (Arush Nand) in the early 1980s, playing with his female cousins. They play dress-up and act out weddings, with Arjie as the bride. (After all, he has the second-hand sari, or wedding dress, and veil, which are the most necessary props for a wedding.) Once his parents find out he is playing feminine roles with the girls, they stop him, sending him off with his boy cousins to play cricket, which doesn’t interest him in the least. When he asks why he can’t play girls’ games, his mother (Nimmi Harasgama) says, “Because the sky is so high and pigs can’t fly, that’s why.”

Without playmates, Arjie is at loose ends until he visits his grandparents and finds his young, cool aunt has returned from university in Canada. Radha Aunty (Agam Darshi) immediately takes to Arjie and helps him realize that he’s special, even indulging his desire to wear makeup and giving him diva lessons: “You have too find a way not to let these boring people rob you of your precociousness. What you have to do is this: [Snaps fingers] Don’t mess with the grand diva!”

As a kind of compromise to his flamboyant tendencies, Arjie’s family allows Radha to get him involved in the local Catholic school’s production of The King and I. (Fittingly colonialist material.) Radha has her own reasons for wanting to be in the play. Although she has been engaged to marry a man through an arranged marriage, she begins to fall in love with another actor in the production named Anil (Ruvin De Silva). Unfortunately, Anil is from the Tamils’ rival ethnic group, the Sinhalese. The relationship feels doomed from the beginning, and both Arjie and Radha are forced to learn painful lessons about the limits of romantic love’s ability to change reality.

The film jumps forward about 8 years to show Arjie as a teenager (Brandon Ingram) enrolled in a Catholic boys’ prep school. He forms a friendship with Shehan (Rehan Mudannayake) also a Sinhal, but one who quotes Oscar Wilde. The boys’ relationship develops into a romance, with Shehan’s mostly empty, shabby-chic colonial mansion as the sanctuary for their erotic exploration. Shehan introduces Arjie to the wonders of British pop music, which was in a particularly androgynous phase in the early 1980s. As in any gay coming of age movie influenced by British culture, there is the ritual playing of Bronski Beat’s “Smalltown Boy.” The boys also share a naked dance in the grand hallway of the house to “Every Breath You Take” by the Police.

Their idyll is broken not by the disapproval of family, although once Arjie’s family figures out what he’s doing with Shehan, they are sufficiently nonplussed, but by the specter of ethnic violence. In July of 1983, Sinhalese mobs roamed through Tamil neighborhoods in and around Colombo destroying businesses, burning houses, and killing Tamils in what became known as Black July. Arjie’s family’s home is destroyed during the violence, and his family barely escapes. Eventually they must flee to Canada as refugees.

The combination of fierce ethnic violence and the squeamish pangs of adolescent yearning make for a difficult mix of tones in one film. In the novel, the worst of the violence is saved for the final chapter in a “Riot Journal” written in Arjie’s voice, which presents a kind of climax of both the ethnic tension and the tension of his self-discovery. Deepa Mehta does her best to wind these two threads together, to mixed success. Nevertheless, Funny Boy is a gorgeously shot and strongly acted film from a true cinematic artist.

Of course a lot of the conflict around gender-bending and sexual identity in both Your Name… and Funny Boy is the residue of the history of colonialism and missionary Christianity in these countries. (In contrast to Taiwan, homosexuality is still illegal in Sri Lanka.) Prior to Western conquest of parts of Asia, many of these places had their own thriving homosexual and transgender cultural traditions.

Chinese literature is full of romantic stories of courtly love between men, like the story of the Cut Sleeve, in which an emperor is sleeping with his lover and awakens to find his long sleeve under his lover’s head. Taken with the beauty of this young man asleep, the emperor cuts the sleeve of his garment, leaving the bed without disturbing his lover. Perhaps in a different era, A-han and Birdy could have found themselves within the tradition of young men known as tuan hsiu: “cut sleeve” boys.

In India, where Tamil culture and language comes from, there is a long history of the hijra—trans or intersex people who dress in feminine attire and often play sacred roles in society. (In Tamil they are known as hiru nangai, or “mister woman.”) Perhaps that is the culture in which Arjie, who knows he looks fabulous in a sari, would have found himself historically.

The unspoken subtext of these films is that even the modern coming-out narrative is its own form of colonialism. The act of planting one’s flag, in defiance of family and society, and claiming one’s identity as LGBTQ is a very Western idea. As the coming-out narrative catches on around the world, older cultural narratives of queerness fall by the wayside. In some cases, these traditional narratives have allowed queer people a place in their societies without the cultural rupture that the more modern form of coming out can cause.

This is not so much a critique as an observation. There is no way to return to a pre-colonial world, and LGBTQ people must be allowed to seek fulfillment in whatever historical context they find themselves. But we should be cautious about seeing the Western coming-out narrative spreading to different parts of the world entirely as a victory for “social progress.” It may be that when global queer communities embrace the modern act of coming out, older and more culturally specific queer narratives are relegated to the closets of history.