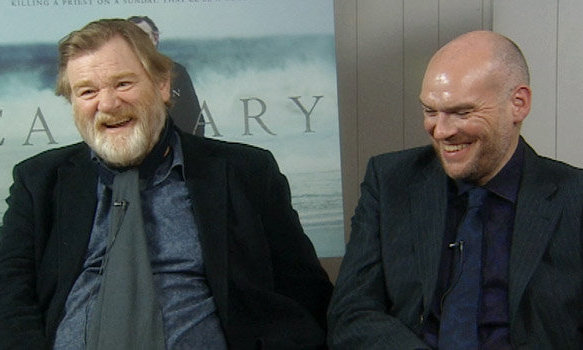

Last week, I had the good fortune to interview Brendan Gleeson and John Michael McDonagh around the release of their film, Calvary. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to speak to them at the same time, so I’ve tried to blend them together into something of a conversation. There are big spoilers throughout, so if you care about that stuff, check it out after you see the film. You can also read my review of the film here.

Ryan Parker: What was your experience of religion (broadly speaking) growing up?

Brendan Gleeson: I make it a rule to not talk about my religious beliefs now because I don’t want people to think I have an agenda in the work that I do. However, I had something of a normal upbringing. My family was Catholic, and I attended Christian Brothers Schools, so I didn’t have to do too much preparation for this role. It was all very familiar to me.

RP: So ministers like Father James were familiar to you?

BG: In a general sense, yes. It was all encapsulated by my parents’ faith, which was simpler then. You either go with the church or not. What the church said really was gospel. That’s an older sense, and I tried to bring that to this role, even though it was a more modern setting. I had an inspirational mentor in school in Pat Grogan. When I looked back on [Calvary], I realized I was probably flying a flag for him.

RP: Is there a place for people like Father James in our world today? Because in the film, it’s plain to see that, even though the villagers know they’re a mess, they certainly don’t want his help. They’d rather spit the communion back in his face, so to speak.

BG: I don’t know if you have siblings, but I grew up with an older brother, and I would go at him until he broke. I think there’s something to that with Father James. The members of the community pour their pain on top of him and try to justify it by making him crumble, but secretly, they don’t want him to. If he breaks, then they have nothing to hope for. Cynicism, disillusionment, and despair carry a caveat at the end of the film. Reconnecting with what is good would be impossible without him.

John Michael McDonagh: Yeah. I’m not certain about this, but my feeling is that maybe a lot of people who would have entered the church or the religious institution [do so] because, generally speaking, they want to help people and help their community. We may find that those people, because of all the scandals attached to these institutions, now do other, different forms of community work or spiritual work [rather than aligning] themselves with a specific creed or religious institution. But those impulses to help mankind have different outlets. Possibly that’s a good thing. I don’t know.

RP: So there is hope?

JMM: I think so. Let’s take a specific character in the film like Dylan Moran’s rich man Fitzgerald, who’s making supercilious comments all the time about how much money he’s got. He’s being quite confrontational on the face of it, and he’s kind of an appalling human being. But if you notice his journey in the movie, by the end of it, he’s the only who’s actually asked for help. He comes to see Father James on the cliff face at the end, and we realize that he’s actually suffering. All the masks have fallen. So if a character like that can asked to be helped and saved, then hopefully there’s hope for everybody. Take Aiden Gillen’s doctor. He’s really abusive. At the same time, he’s helping people in his community. He’s saving lives as a doctor. The important story he tells towards the end about the child whose operation went wrong…the subtext of that could be that he was really affected by that when it happened. […] If an act like that can turn [you] into a negative person, another act can turn you back. And the priest tells Veronica that no one is a lost cause. At the end, in the conversation, he says it’s not too late. So I think that’s a subtext throughout the movie, and it’s there in all the characters.

BG: Yes. [Father James] lives on in his daughter. They have connected even though he abandoned her twice. And SPOILER O’Dowd’s character picking up the phone wasn’t a foregone conclusion. But having him do that has us staring up at the end of the film rather than down.

RP: Brendan talked about the scene at the end where Fiona visits the prison. Did you ever envision a different ending?

JMM: I always wanted to have a montage of the characters in that kind of It’s a Wonderful Life sense. Once Father James is gone, what does that mean to everyone else. We’re not sure what it means. Some of those characters will carry on being the same as they are. But some may have changed. But I also wanted it to end on a moment of hope. I felt the film was somber enough. I wanted the final shot to be kind of a grace note. One thing I did change to make it more hopeful was when she motions for the killer to pick up the phone. In the original draft he doesn’t, but again, I wanted the film to end on a much more hopeful aspect. Shooting that scene on the beach, the performance was so emotional that I wanted to keep it going. [The killer has] destroyed the priest, but he’s also destroyed himself. But by picking up the phone, he may have still saved himself.

RP: Could you say a bit about the state of the villagers in the film? As I watched the film, I began to see them as these larger-than-life characters almost representative of major moral and ethical shortcomings.

JMM: They weren’t trying to be symbolic of anything. If you try to create a work of art, if it’s rich and dense enough, the audience can get whatever meanings out of it they want. It should be open to multiple interpretations. I think, you know, I do tend to create heightened, non-naturalistic characters. They are all a little idiosyncratic and eccentric. It’s interesting, since I’ve been doing this press tour, in Chicago I spoke to an Episcopalian minister and in Dallas a Methodist minister, and they both couldn’t understand why the characters were being referred to as heightened, because they meet those sorts of people every day. To them it was realism. I was kind of happy to hear that. Maybe I shouldn’t talk about these characters as being heightened. Maybe you meet any one of these any day of your life. And these ministers were both saying that people are very angry, and they’re trying to help people who are very angry toward them and church institutions, which I found interesting because you’re telling a story that you hope is parochial, but you also hope it is universal.

RP: Calvary can easily be seen as an indictment against the church, but the inclusion of these rowdy villagers seems to point to something else.

BG: It is the church, but it’s not just the church. It’s the individual as well. The individual has a responsibility to not slip into disillusionment and despair, and you see that throughout the film.

RP: There are so many sharp lines of dialogue that convey the themes of the film. In fact, it’s one of my favorite aspects of both this and The Guard. Is there one that means the most to you or that conveys more of what you were getting at with this film?

BG: Father James’ line, “Forgiveness is highly underrated.” That’s a big one. It seems that the church has forgotten the essentials and become obsessed with minor rules and regulations. That would be the one.

JMM: I really like the dialogue between Fr. James and his daughter Fiona in the confessional. It’s a philosophical discussion, but it’s also a discussion between a father and a daughter and the daughter is in a lot of pain. It also hints at the fact that they’re both literate, erudite people, very intellectual people. She is her father’s daughter. I think that then resonates at the end, that she takes on the mantel of her father really. I like that scene.

RP: I’d like to shift the conversation a bit and talk about your larger body of work, which, in many ways, is similar to your brother’s (Martin McDonagh) in its darkly comedic tone.

JMM: I like writing really dark scenes. I like the scene with Domnhall Gleeson [in Calvary]. There are some very very dark things being said there. I like broadly humorous scenes as well. I like the scene when Dylan Moran takes down the painting and does something awful to it. Obviously the whole film is very tonally comic and tonally tragic. I like writing both of those sorts of sequences. When I’m sitting alone in a room three or four hours a day writing a script, I’m trying to keep myself interested as much as some prospective audience, so I write scenes that amuse me in one way or another.

RP: Putting this film in conversation with The Guard, I am a big fan these film because they provide fully realized worlds. By that, I mean that when the narrative promises something, the characters follow up on it. There are no easy ways out. I think this is also true of Martin’s work in In Bruges and 7 Psychopaths.

BG: Every character in these films could have a separate story all their own. [The McDonaghs] are brave in where they bring us. I was in a short with Martin, and I thought he was taking it too far. He told me, “All my work is about love.” Now, there might be hard stuff around it, but it’s all about love.

JMM: Yeah exactly. I take that as a huge compliment. The main thing for me is I’ve found a lot of movies, after the first 10 minutes, you know what the ending will be. You may as well not sit through the rest of the movie. Hopefully, I think with myself and my brother’s movies, because of that tone that switches back and forth between the comedic and the tragic, the audience is slightly wrong-footed all the time, so they’re never quite sure where it will go or how far it will go. We both have that in common. The conclusion of [Calvary] was a sort of discovery. I always knew that was going to be the conclusion, but I never had the identity of the killer until two-thirds of the way through. That’s when you’re kind of working things out as you’re getting to that stage. I always know what I’m going to do at the start of a film and what I’m going to do at the end, so I never waver from that course.

RP: Three films, In Bruges, The Guard, and Calvary have similar settings and similar lead characters. Brendan seems to always play characters that see the world as it really is, or sees something that no one else sees. Both these lead characters and the writing behind them seems to serve a priestly function.

BG: Yes. There’s an arc to what actors do. […] I try to find humanity in all the characters I play. No one sees themselves as a devil. If I’m playing a good man, I try to find the faults in that character too. I just try to make them as human as possible.

JMM: Brendan likes to say that art makes you feel less alone. I’ve always felt that was a good quote.