W.H. Auden once described his spiritual mentor as a man of such genuine piety that you did not feel compelled to be upright or good around him, but when you were in his presence, you never imagined you would want to do anything wrong.

I’ve been lucky to meet a few such people in my life. They’re not what institutional religion has taught us to expect from “saints.” They’re quick to laugh, often at their own earthy humor. You’re likely to learn as much from them sharing a drink or a meal as you are from any sermon they could preach. They’ve often wrestled with significant personal demons, but with such incredible honesty that those around them learn from their struggles. Sometimes in their presence, but often in reflection, and sometimes not until after their death, you realize these personalities offered you a window into something greater. And if somehow we could all be a little more like these people–as honest, funny, wise, and vulnerable–we might just find ourselves as close as we’ll get in this life to a kingdom of God.

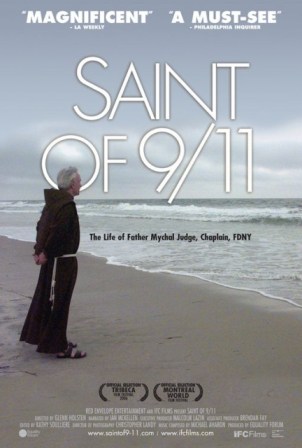

Saint of 9/11 tells the story of such a figure: Father Mychal Judge, a Franciscan priest and chaplain of the New York Fire Department who was killed in the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. An iconic photo, which appeared in publications across the country after the attacks, showed his lifeless but serene body being taken from the wreckage by distraught firefighters. I was skeptical of this film, particularly because its title seemed like too much of a canonization. But after watching it, I was convinced of what an incredible person Father Mychal must have been, and I have no doubt that as much as we can say there are saints, he was one.

Stories abound in this film about his goodness. How a friend gave him a coat to get through the frigid New York winter and the next time he saw Father Mychal he didn’t have the coat, and his friend knew immediately he had given it away to a street person. How when faced with the AIDS crisis, Father Mychal gave solace to the sick and the dying, sometimes rubbing their feet with holy oil as a way of easing into conversation with those who had been despised and rejected by their churches and families. The heart-wrenching story of Father Mychal giving last rights to a dying gay man as his partner and friends looked on, giving him communion, then holding him in a healing embrace. His lifeless body being placed in the altar of a nearby Catholic church in a way that reminded the firefighters of a modern Pieta. These are the kinds of stories that get retold and magnified about “saints,” until some generations removed, when their everyday acts get turned into performing miracles and raising the dead.

But what convinces me of this man’s inherent goodness is not the stories themselves, although they’re certainly believable, but the wonder and joy with which his friends tell them. The filmmakers do a fantastic job of letting those who knew him best drive the narrative of the film with their stories. And, as might be expected of such a genuinely kind and decent person, his friends come from all walks of life. There are lots of ruddy Irish American New Yorkers that tell the stories, but also street people, AIDS activists, nuns and priests, then-Senator Hillary Clinton (speaking at his funeral) and of course, the New York firefighters whom he loved and served so devotedly.

The stories form a kind of gospel around this man, as his friends spread the word about his acts of goodness and mercy. It reminds me of Bishop Spong’s admonition that we should not concern ourselves with discerning the absolute historical authenticity of everything Jesus did, but focus instead on the “Christ event.” What was it that was so remarkable about this man that people told stories about him healing the sick and walking on water? What was it that made them say after he was gone, “Were not our hearts burning within us while he talked with us?” (Luke 24:32)

That the film comes off so well is a testament to the dedication of Father Mychal’s friends. After the re-election of George W. Bush, rightly or wrongly attributed to the influence of conservative “values voters,” there was a rush from religious liberals to start getting their stories into the media, and as so many filmmakers did during the ‘aughts, many of these stories took the form of documentary. Some of the results were good and some were bad—but the labor of love that this film must have been comes shining through in the quality of every scene. The one questionable choice was enlisting Ian McKellan to read passages from Father Mychal’s sermons, letters, and journals. I’d listen to Sir Ian read the phone book, but the point of the film was what a down to earth, human “saint” this man was, which is a little hard to imagine when his words are illuminated by the stentorian tones of a Shakespearian actor.

If Father Mychal were any ordinary saint, the canonization drums would have already begun beating, no doubt with miracle stories popping up to be investigated by the Vatican. But even here, the man was so extraordinarily honest, he blew his chances at official beatification. As far as anybody knows, Father Mychal was always faithful to his priestly vows, but Father Mychal was also a self-identified gay man. He took issue with the Church’s policy on homosexuality, was disgusted by the Church’s spiritually callous reaction to the AIDS crisis, and is on record as stating to bereaved families of victims of the plague that their gay sons and their gay sons’ lovers and partners, were blessed and accepted by God. Something about this Irishman and Franciscan (an ornery combination if there ever was one) would not let the institutional church get in the way of telling the truth and ministering with genuine love. Here’s hoping there will one day be a church that can recognize what a saint Father Mychal must have been to lovingly and passionately disagree with the most damaging structures of religion while still dedicating himself so selflessly to the Christian Gospel.

When this film came out, several more orthodox friends of Father Mychal were shocked–shocked–that gay rights radicals would try to exploit this holy man’s death by spreading the “lie” that he was gay. But even their ignorance was a sign of the man’s piety. He only told people about his sexuality who wanted or needed to hear about it; he would never have imposed this information on anyone if he thought it would make them uncomfortable, or if it would compromise his ministry.

And besides, the New York fire commissioner says he knew. And I don’t have the gall or the boxing moves to call him a liar.