The biggest question I had while watching the BBC/FX remake of Black Narcissus (Streaming on FX/Hulu) was, Who looked at the original 1947 film and thought, “We know what went wrong and we know how to fix it”?

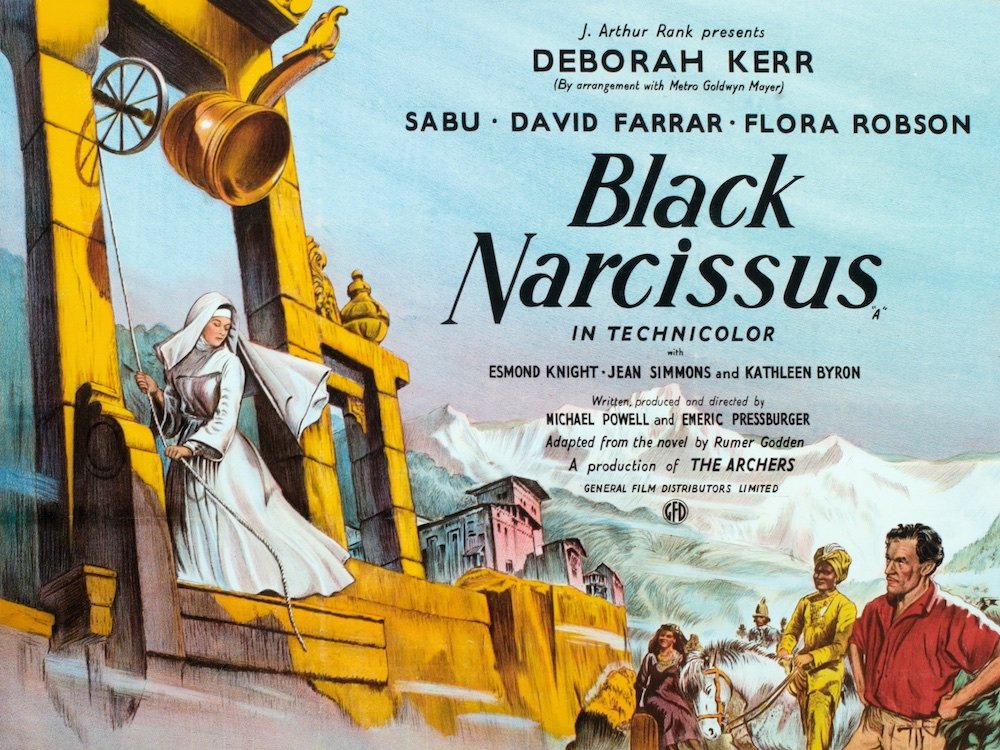

Black Narcissus (1947) is a British film directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger–an erotic melodrama about a group of Anglican nuns that start a hospital and school at a remote location in the Himalayas. The building where they set up was once a “House of Women,” the former dwelling of the harem of a local Indian Raja. Deborah Kerr plays Sister Clodagh, who leads the small band of nuns to start the Convent of St. Faith in this unlikely location. David Farrar plays Mr. Dean, a roguish British agent who Sister Clodagh argues with incessantly but really secretly desires. Kathleen Byron plays Sister Ruth, whose lust for Mr. Dean and emotional instability lead to tragedy.

The BBC/FX remake, directed by Charlotte Bruus Christensen, extends the story to a 3-part miniseries. Gemma Arterton plays Sister Clodagh, Aisling Franciosi plays Sister Ruth, and Alessandro Nivola plays Mr. Dean—all very competently. The series is one of the last performances of Diana Rigg, who plays the Mother Superior of the order.

In the remake, the cast has changed, but the plot mostly hasn’t, although things that were only hinted at in the 1947 film are spelled out more clearly. In drawn-out, sensual flashbacks, we are made to understand that Sister Clodagh joined the order because of a failed love affair. We recognize that Sister Ruth is mentally ill, seeing hallucinations that suggest psychosis. The remake introduces one important new character—a clueless priest played by Jim Broadbent. He visits the convent and overrules Sister Clodagh’s request that Sister Ruth be sent back to the Mother House for psychological evaluation.

The 1940s Black Narcissus is mostly known for its Oscar-winning cinematography and set design, which conjured the Himalayas from matte paintings and lighting effects shot almost entirely at Pinewood Studios in England. Deborah Kerr plays a woman divided by ambition and repressed passion. David Farrar is a grown man who wears shorts and rides a donkey, making you realize how desperate these women must be for male flesh if they find him attractive. Kathleen Byron steals the whole show with a final breakdown that veers deliciously into camp.

The BBC/FX remake uses actual location footage from the Himalayas, casts a total hunk that no one could resist as Mr. Dean, gives us deeper insight into Sister Clodagh’s repression, and invokes sympathy for Sister Ruth’s mental illness. It thereby takes away all the quirks and oddities that made the original film interesting, and gives us nothing new in return.

The 1947 film had two clear messages: 1.) Women, when placed alone in stressful situations, will break down into feminine weakness, doing stupid things like falling for unattractive men and planting flowers in the vegetable garden. They just can’t help it, they’re made that way. 2.) The East is a sensual and decadent place and will resist any “civilizing” influence from the West. This was perhaps what audiences believed as the original film was released in the year the British occupation of India ended.

As the remake is supposed to be an updated version of the story, I kept waiting for the nuns to have some inkling that the system was rigged against them. That they would never succeed as long as their fates were decided by men—whether by the priest, or Mr. Dean, or the Raja. And that their project was destined for failure because of the moral rot of colonialism, not the backwardness of Indian culture.

Instead, the remake ends up focusing on personal failures of the characters—lust, ambition, bad life choices—or forces outside human control—mental illness, karma. The greater social issues remain unexamined.

Perhaps one might argue that this kind of awareness is beyond the scope of the story and its characters in the time in which it takes place. Then how about leaving this story and its worldview in the past, encased in a beautifully crafted and entertainingly bizarre film that can be studied as a curiosity of its time. There’s a reason not every film has to be remade.