There are times in history when the veil between the daily struggle for doing good and the cosmic struggle for justice becomes thin. We are living in one of those times. During these eras, the culture brings forth apocalyptic works that help us imagine a path to a new age of justice. It happened with Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar in the Vietnam era. It happened during the AIDS era with Angels in America. And it is happening now, in the age of Trump, with Wonder Woman.

Wonder Woman takes much of the movie mythology of blockbusters and adapts it to a heroic woman. Diana, princess of the Amazons, enters the world of men (and in this case, it really is “men,” having grown up in a completely feminine society) versed in the classics and the sciences, able to speak all human languages and possessed of supernatural instincts and reflexes. She is as powerful and capable a superhero as any male. In Wonder Woman the film, there are elements of Arthurian legend, The Odyssey, and the hero’s journey.

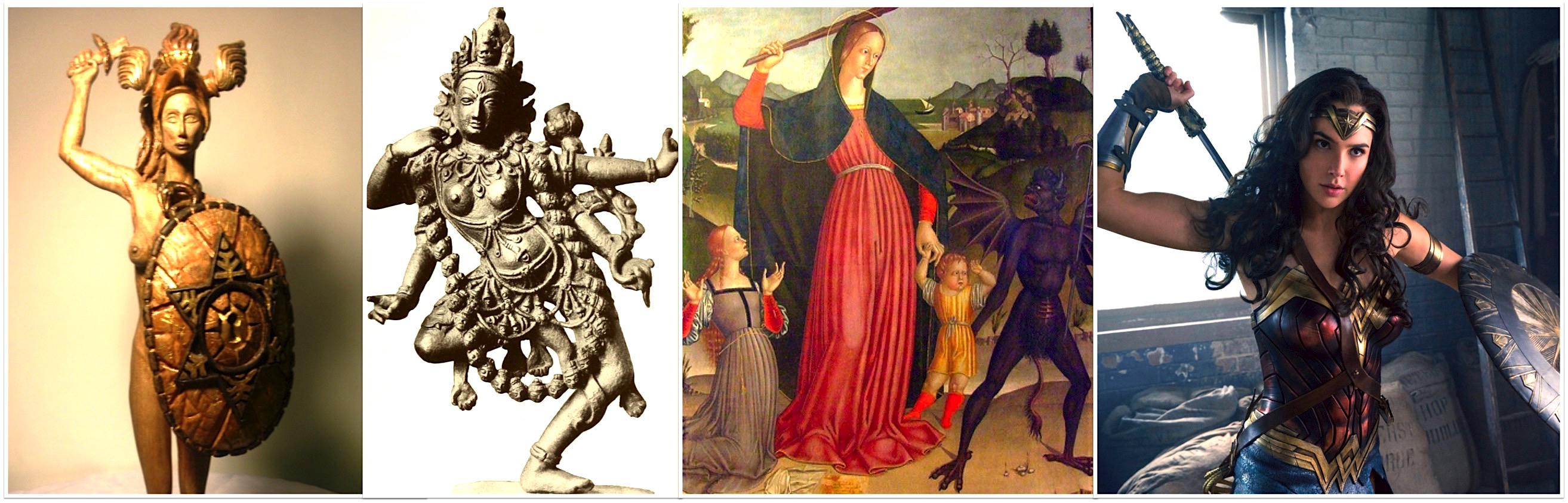

All of the standard objections to the deification of superheroes apply to Wonder Woman: from the anti-democratic tendencies of the “American Monomyth,” to the liberal Christian objection to the myth of redemptive violence. But, particularly at this time, it is helpful to see a woman hero who knows what she believes and acts passionately from a position of strength and power. Our superhero myths may be imperfect, but seeing familiar stories placed in the hands of a woman–indeed, a goddess figure–is revolutionary.

This film comes at a time when I have been questioning my own doctrine of God. My recent post on The Handmaid’s Tale made me wonder how Christians can have a concept of God that is multi-personal, relational, and yet totally male.

I went back and did some reading I should have done in seminary, from Sexism and God-Talk by Rosemary Radford Reuther. In Reuther’s account, the monotheistic Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) evolved from older Middle Eastern religions that imagined a goddess/god in a dependent relationship with each other. The male god, Ba’al, had a consort named Anat. Each year, Ba’al, the God of rain and thunder, would fight with Mot, the god of drought and death. For a time, Mot would win, and Ba’al would appear to be dead. But through his union with Anat, the goddess of fertility, he would be resurrected and bring new life with the spring rains and the growth of new crops.

The Hebrews were nomadic herders, and competed with the Canaanite farmers for land on which to graze their sheep and goats. The Canaanite Ba’al, an agricultural god, became their enemy. But the worship of the Hebrew “sky god” Yahweh, didn’t completely destroy the idea of a god/goddess relationship. For centuries, in the popular imagination, the goddess Asherah, often given names like “Mother of Gods” and “Queen of Heaven” was worshiped alongside of Yahweh, and even thought of as his “wife.”

Over time, the patriarchal cult of Yahweh began to see the feminine idea of “goddess” as something to be defeated and subdued. This represented defeat of a rural and transient culture by the urban elite of the Israelite cities. Eventually, even feminine descriptions of the Spirit of Yahweh, like Sophia, the mothering wisdom who hovered over the formless void and provided the divine spark that created the world, was replaced with more the masculine Logos, or “Word,” as in the “Word of the Lord.”

The variation of Jewish religion known as Christianity was so male-centric that Christians created a Holy Trinity made up entirely of male figures. According to the Roman Catholic Church, the Holy Spirit continually proceeds from the mutual love of the Father and the Son, and is even seen as the template for heterosexual matrimony!

So one of the most homophobic institutions in the world worships two masculine divine figures whose love for each other causes the procession of a third divine person. I’m all for a homonormative understanding of relationships, but this confounds even the most basic human understanding of the creation of a “person,” whether “begotten” or “made.” The Holy Spirit has two daddies.

Goddess worship was far from eliminated from Christian practice, however. The feminine divine can be found in all manner of female saints, and most importantly, in the Virgin Mary. Although Catholic sources take great pains to stress Mary’s humanity (despite being born without sin) and her humility and complicity with God’s plan, she has still be elevated to a similar position as Asherah – that is, “Queen of Heaven” and “Mother of God.”

Some have even taken their Mary worship to extremes, like Saint Maximilian Kolbe, who formed the Militia Immaculatae prior to World War II. He said that because of her immaculate conception and her part in the divine conception of Jesus, Mary was a quasi-incarnation of the Holy Spirit. Far from the mothering figure of infinite mercy, he saw Mary as a figure of wrath, Destroyer of Heresies, crushing the heads of the enemies of Christ. In this mother/warrior dichotomy, she takes on a form like the Hindu goddess Kali, who dances on the corpses of her slain enemies.

Many Protestants accuse Catholics of making Mary the “fourth person of the Trinity.” I think they’re wrong about that. I think Catholics make Mary the third person of the Trinity—the icon and perhaps even personification of the Holy Spirit. And maybe we Protestants need to get on board with venerating Mary.

After all, without Mary, there would be no salvation through Jesus Christ. Maybe we should begin seeing salvation as a cooperative act of incarnation on the part of Mary, and sacrifice on the part of Jesus. We could see Mary as a personification of the ancient spirit of Sophia, the feminine creative principle who was with the Creator from the beginning. Together they turned the formless void into the beauty of the earth. Together they collaborated to bring salvation to human beings in the form of their divine child Jesus. Maybe we should see Christ’s miraculous birth through Mary not as an act of passive submission to a controlling Father God, but something she brought forth from within herself.

This act of Mary’s divine creativity is spoken forth in the prophetic words of the Magnificat:

My soul magnifies the Lord,

and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior…

He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts.

He has brought down the powerful from their thrones,

and lifted up the lowly;

He has filled the hungry with good things,

and sent the rich away empty. (Luke 1:46-47; 51-53)

This sounds like exactly the kind of Goddess prophecy we need right now.

We certainly need something fierce and feminine at this moment. As I suggested in my Handmaid’s Tale post, I don’t think America is turning back on itself; I think we’re at a threshold. A well-educated, global-thinking, diverse generation is coming of age and into power. Many of the most marginalized of this generation—women, people of color, LGBTQ folks, immigrants—are no longer asking, they are demanding their place. Those who cannot accept this new reality feel so threatened by this inevitable, unstoppable shift that they have struck back in a fit of electoral violence, electing the most corrupt, depraved, and boorishly masculine administration in the history of the country. Leading the way were Christians who were willing to sell their moral birthright for the mess of pottage that now festers in the White House.

Wonder Woman represents the change we’ve been waiting for, and the one we’ve been too afraid to embrace. The change that could come in the form of the divine feminine.

If Wonder Woman is a harbinger of a new age, I’m ready for the end times. I’m hooked on the apocalypse. I want to be caught up in the Rapture. I want to see the return of Christ in glory.

I’m just not sure how many of my fellow Christians will recognize her when she comes.