For a Protestant, doing things in a Catholic setting is like going to a foreign country where they speak English. You can understand what they’re saying, but you’re in a land of different cultural cues. You spend a lot of time playing the Venn-diagram game of What’s the same/What’s different. So it was when as a Presbyterian I found myself on a silent retreat at a Jesuit spirituality center in Louisiana.

I went on the retreat because I had heard about the Jesuit discipline of discernment. This is the practice of “testing the spirits” to see where God is leading you. The Jesuits were founded by Saint Ignatius of Loyola, a sixteenth century Basque nobleman and soldier. His theological masterpiece is the Spiritual Exercises, essential reading for spiritual direction. This program of visualization, prayer, and insight into human psychology, forms the backbone of Ignatian spirituality.

I came to the Jesuits with what must seem like a strange dilemma, at least to be sharing with an arm of the Catholic Church. The first twenty years of my adulthood have largely been taken up with figuring out how to be a gay man and a Christian. These last two decades have been eventful times. Coming out in my early twenties meant I came of age when being gay was transforming from a subculture that only existed in major cities to a progressive cause célèbre. Same-sex marriage became a legitimate policy goal. In a parallel movement in the liberal Protestant churches, ordination of gay people became the main topic of debate.

Twenty years later, the same-sex marriage movement reached a dramatic denouement with the Supreme Court rulings of 2013 and 2015. At almost the same time, the ordination debate was settled in the most of the mainline Protestant churches, including the main body of Presbyterians to which I belong.

During this time, the Roman Catholic Church, its future still determined by a kyriarchy of old men, has worked to silence reconsideration among its theologians and moral ethicists on the subject of homosexuality. The year I was born, 1975, Jesuit Father John J. McNeill published The Church and the Homosexual, intended as a first salvo in what he hoped would be a discussion leading to the Church’s reconciliation with the gay community. McNeill’s book first received a cautious imprimatur from the Vatican, only to have it snatched away shortly after its publication. McNeill was silenced, and eventually forced to leave the order by his superiors. The modern-day Inquisition against McNeill was led by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, later to become Pope Benedict XVI. McNeill died this year, never seeing the Church and LGBT community he loved reach reconciliation. So why on earth would an out-and-proud gay man like me go to the Jesuits with his midlife crisis?

The Jesuit Spirituality Center at Grand Coteau

The driveway leading to Saint Charles College at Grand Coteau, Louisiana is flanked by rows of towering pines. The parking lot sits underneath a white plaster statue of Jesuit benefactor Saint Charles Borromeo. The grounds are a graceful 700 acres kept in a genteel agricultural style: pastures punctuated by live oaks, pecan trees, and historic outbuildings, including an elegant cross-shaped barn with double silos in front that looks like it was built as a cathedral for cows.

The College of Saint Charles has a long history in South Louisiana. Founded in 1837, during most of the nineteenth century it was a school for the sons of wealthy merchants and professionals in the decorous “Prairie Cajun” country that surrounded it. Through the heart of the twentieth century, it closed itself off from the outside world, and became a seminary exclusively for the training of Jesuit priests. In the 1970s, it opened itself again to outsiders, providing a site for lay retreats. In addition to this function, it still serves as a novitiate, or center for young men in the first two years of priestly discernment, and as a retirement home for elderly Jesuits. To observe the daily life of the full-time residents is to see the bracketing stages of the four ages of man on stark display, with a dozen or so young men fresh from college mingling with the old Jesuit Fathers in wheelchairs.

The College building itself is a massive whitewashed brick castle, complete with ornamental ramparts. Recent renovations have attempted to make it more homey, with comfortable spaces inside and out for quiet contemplation. Approaching the front door, there is a wide slate patio with wooden rocking chairs. Inside are common areas with wicker furniture, oriental rugs, and lazily spinning ceiling fans, a Deep South décor reminiscent of a Tennessee Williams set. The bedrooms in the retreat center are comfortable and have the recent novelty of en-suite bathrooms. Yet it’s hard for someone with a sense of history to ignore the architectural message of the stern exterior and the small cells the college’s residents once lived in. While everything about the retreat center says: rest…renewal…contemplation, everything about the building says: study…work…discipline.

At the beginning of the retreat we met in a group, maybe eight or nine of us, with a cheerful and stylish lady-of-a-certain-age as a retreat director. In outlining the retreat process, we were made to understand that silence would ensue after our first meeting until we met again on Sunday morning. We were warned that the retired Jesuits would impishly try to get us to talk in the hallways and elevators, but that our only conversation should be during a one-on-one meeting with the retreat director on Saturday. Even meals were to be taken in silence, with physical proximity to our fellow retreatants as our only interaction. This silent retreat with the spiritual director as the only conversation partner is the standard practice for Jesuit retreats. We were there for only three days; in their novitiate, the Jesuits do it for thirty.

The last thing the retreat director told us was that we were in sacred company, because the rooms, common spaces, and chapels in this building had been the location of prayer for more than a hundred years.

This got me thinking about the residents of St. Charles College over the last century, who would have been almost entirely men. And when I think about large groups of men in homosocial environments, I wonder what possibilities there were for intimacy or affection between them. How many of them sought out this environment because they craved masculine intimacy? How many of them sought it out because they wished to cure their desire for masculine intimacy? How many of them ardently prayed against their sensuality for the salvation of their souls? In short, how many of the men who inhabited this place were my gay brothers?

Life on the Holy Farm

John McNeill, who first crashed the door of the Jesuit closet, wrote in his spiritual autobiography, Both Feet Firmly Planted in Midair, that initially his vocation had as much to do with denying his sexuality as pursuing God:

I was still ambivalent about my vocation, which was still based primarily in my fear that as a gay man the only way I could get to heaven was by denying and suppressing my sexuality and my desire for human love and my belief that the only way to accomplish that denial was to enter a religious order, which would provide the environment and support for a life of celibacy that was possible and meaningful.

I don’t know the statistics on how many priests have been gay men. No one does. There have long been suspicions that the numbers are well above those of the general population. We do know the demographic conditions that led to vocations in the past: large immigrant families of Irish, Italians, Germans, and Poles with too many mouths to feed who could always spare a son to send into religious life. It seems likely that the gentle and studious ones would be sent first.

The crash of world events in the last century—World War, Depression, World War, Cold War—would leave masses of young men looking for livelihood, direction, and a balm for damaged conscience. These conditions along with Church’s and society’s repressive approach to homosexuality would surely have lured many more men like John McNeill into the priesthood. In fact, McNeill, an Irish Catholic, World War II veteran, and gay man, fit the mold perfectly.

The story of St. Charles College in the last century matches this history. It was shortly after World War I that it closed its doors to the sons of local gentry and solely became a seminary for the training of Jesuits. The apex of the college’s vocations came after World War II, when hundreds of men swarmed the order. Fittingly, the reopening of the College to lay ministry came as vocations dwindled in the 1970’s. It’s easy to read several factors into the history here: birth control, sexual revolution, and undoubtedly, an ascendant gay community.

During the golden era for Jesuit vocations between the 1920’s and the late 1960s, the land around St. Charles helped support the community within. That holy barn housed animals that supplied milk, cheese, and eggs. Histories of the college say the chief crop grown on the land was sweet potatoes. In addition to the continual work of prayer and study, men called to vocations would have worked in the fields and barns to supply their food.

This leads to an evocative image of holy work, as the young brothers went into the

steamy fields to quarry their dinner from the ground. What is the proper Jesuit dress for potato-digging? Surely they ditched their black cassocks for work clothes, donning the loose-fitting dungarees of workmen and prisoners. Perhaps after several hours in the field, comfort would be allowed to impinge on modesty. Maybe they would even strip to the waist and let their skin glisten in the sun. A ladle and bucket nearby would lead to impromptu baptism, the flow of cold water lifted to drench their hair and splash over their chest and shoulders

And not only would they have prayed, studied, and worked, but they would have played. Walking the grounds of St. Charles today reveals evidence of a physically dynamic community that once lived at the College. Courts for tennis and handball sit like ancient ruins overgrown with grass. A white-framed outbuilding with archaic gym equipment is still used by the novices. A large patch of new grass marks the spot where an Olympic-sized pool was recently declared unfit for use and filled in.

In the 50s, the campus must have fairly buzzed with physical activity: brothers hurrying to classes and chapel, hefting hay bales and sweet potatoes, competing with one another at sports. It’s easy to imagine the wide grounds being used for pickup games of baseball and football. The Jesuit pool parties must have allowed for release of pent-up energy after long mornings of study or fieldwork–brothers splashing and wrestling in the water, a transistor tuned to the cradle strains of rock-n-roll. And safely hidden behind the azalea bushes, they likely swam nude, as was the standard in same-sex swimming areas at the time.

The interest in the dress and undress of the novices is not simply a factor of my overheated imagination. I want to know what level of sensuality was allowed in this buttoned and cassocked place. In settings of religious training, the cloistering of the body went along with the cloistering of the mind and spirit. But under what conditions could these young, energetic male bodies break out of their black serge and find communion with each other?

Soldiers for Christ

Saint Ignatius himself would have been proud of St. Charles’ history of work, study, and vigorous activity. The order he founded was intended to bring together attractive and physically capable young men, “Soldiers for Christ,” to devote themselves with absolute obedience to their earthly superiors—literally called “generals”—and to Christ, their heavenly general. The Spiritual Exercises were designed to create an intimacy with Christ like that of brother soldiers, their hearts on fire for God. The fealty to the order was unto death, and in fact, the Jesuit burial ground behind the College features identical white headstones arranged in rows, like a military graveyard.

The Jesuit motto, “Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam,” “For the Greater Glory of God!” has a militant ring to it. The more cryptic abbreviation AMDG is seen in various decorative details around the campus. (I once knew a Jesuit who had it tattooed on his chest.) This Latin motto, along with the sunburst symbolism of the Jesuit crest has led to many overheated internet conspiracies about the order’s role in the Illuminati.

Whatever their pretensions to military discipline, the Jesuits are also known for their intellectual heft. The period between novitiate and ordination can be more than a decade. During this extended discernment, the brothers are expected to teach in high schools and colleges run by the order, do works of charity, and study continuously. Many rack up multiple graduate degrees during this time, and the Jesuit contributions to fields as diverse as math, physics, anthropology, astronomy, music, education, psychology, sociology are enormous.

Although this regimen would seem to produce an order of brains and little feeling, the Jesuits were some of the first proponents of what we today call “emotional intelligence.” Spiritual Exercises is the original psychological self-help book, asking readers to look deeply within their own hearts and weigh the emotions found within. Positive feelings of love, joy, or even cleansing tears are considered a sign of God’s closeness, or “consolation.” Feelings of doubt, confusion, and anxiety suggest God’s distance, or “desolation.” When making a difficult decision, it is sieving through these feelings and weighing the results that can lead to a decision that results in greater intimacy with God.

Jesuits are finely aware of the intricate movements of the human heart. In fact, in contrast to some spiritual traditions that seek to squelch desire, Ignatian spirituality sees desire as something that God has planted in the individual. When you follow your true desire, you follow God’s path. Although focused on spiritual desires, this self-awareness makes it difficult to ignore desires and movements of the body as well—the rise and fall of the fundamental forces of hunger, illness, wakefulness, and libido.

Almost as though this confusion between spiritual desire and bodily desire was expected, the old Jesuits practiced chastisement and mortification. McNeill wrote that even in the 1950’s Jesuit students would still flagellate themselves with short whips. At certain prescribed times, they would use the cilice, a chain that is clasped around the thigh with barbs that dig into the flesh. One wonders how effective this fleshly punishment actually was for suppressing sexual desire, or if it simply bent the novices’ predilections toward BDSM.

The Miracle of Grand Coteau

Yet despite the discipline of the place, there was one holy and sensual assignation on the grounds of Grand Coteau—this time between a young man and a woman—that is still celebrated today as a miracle. Even more remarkable is that one of the participants in this spiritual intercourse had been dead for almost 350 years.

The Jesuits were not the first religious order to settle on the fertile ridge above the Bayou Teche. The Sisters of the Sacred Heart were there more than a decade and a half before, setting up their convent and school for girls in 1821. When the French Jesuit missionaries arrived looking for a place to found their boys’ college, they pledged cooperation with the sisters. To signify their dedication, they created a path between the two schools lined with Louisiana live oaks. You can still wander the path, about a mile between the schools and a bit worse for wear, the oaks spreading their Spanish moss-draped branches over the potholed gravel parkway.

In 1866, a young woman of nineteen, Mary Wilson, fled her parents’ home in New London, Ontario to join the Sisters of the Sacred Heart. Wilson’s parents were Protestants; in fact they were Presbyterians, like my family. This was a time when people didn’t just switch religions, so Mary joining the Catholics, much less a religious order, must have seemed to her parents like she had been abducted by aliens.

After a long trip down the Mississippi, and an arduous journey from New Orleans across the Atchafalaya swamp by train, boat, and stagecoach, Mary found herself housed in the stately, French Colonial brick convent at Grand Coteau.

The journey left her weak, however, and before she could “take the veil,” that is, join the order as a novice, she fell violently ill. She began vomiting blood and could not keep down even the smallest amount of food. As her convulsions continued, eventually fluids and medication were abandoned as well. The convent doctor, Dr. Edward M. Millard, said there was nothing he could do for her.

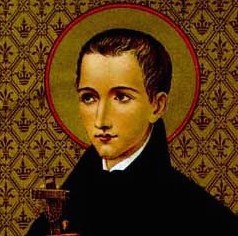

The sisters began saying a novena for God’s intercession and healing of Mary. Novenas, or nine-day cycles of prayers, are often said in appeal to a particular holy figure. The sisters chose to pray to Blessed John Berchmans, a seventeenth century Jesuit scholastic who had recently been beatified after two confirmed miracles. One more miracle and the long-dead young man would become a saint. The sisters placed a holy card of Berchmans in Mary Wilson’s room as she suffered through the agony of her illness for eight weeks.

John Berchmans and Mary Wilson had a lot in common. A headstrong teenager like Mary Wilson, Berchmans left his Flemish family against their wishes to join the Jesuits at age 17, in 1616. It is said that he told his parents, “If the very clothes I have on kept me back, I would strip them off, and follow Christ like the young man who cast away his linen cloth.”

This naked devotion was a reference to a strange incident in Mark, Chapter 14. As Jesus is seized by the Temple authorities, the gospel writer tells us, “A certain young man was following him, wearing nothing but a linen cloth. They caught hold of him, but he left the linen cloth and ran off naked.” The writer does not explain who the young man was, or why he was so thinly clad in the presence of Jesus.

Berchmans, like Mary Wilson, also took a grueling journey to follow his vocation, walking more than 900 miles from Antwerp to enroll at the Roman College, now known as the Gregorian University, the flagship Jesuit institution of higher education. During his two years in seminary Berchmans made a reputation for himself as a scholar and philosopher. At the beginning of his third year, however, he contracted malaria and died. He was only twenty-two. His death was unfortunate, but his ardor for his faith made him one of the Church’s most popular holy figures for the young. After his canonization, he became the patron saint of altar servers, permanently preserved as a Catholic poster boy.

So why did Mary and the convent sisters pray to him? Perhaps there was renewed interest in Berchmans after his beatification just a year before. Perhaps Mary felt drawn to his personal story—religious vocation as a form of adolescent rebellion. But looking at the holy card images of Berchmans, it’s hard to escape just how handsome he is. His long, Gallic nose, high cheekbones, dainty mouth and chin, and large, dewy eyes make him seem like a proto-Bieber, a teen idol before his time. Could Mary’s attraction to John Berchman’s have been more than spiritual? Something more like a teenage crush?

Whatever her reasons, suffering greatly with blood caked in her mouth and her fingers and lips turning blue, Mary offered the holy boyfriend a prayer. Well, more of an ultimatum. Placing her holy card of the Blessed Berchmans on her lips, she said, “If it be true that you can work miracles, I wish you would do something for me. If not, I will not believe in you.”

She then heard someone tell her to open her mouth. She felt a finger placed inside her mouth, and her pain stopped completely. She looked up and saw a figure standing before her holding a cup, with his face shadowed by bright light glowing behind him. She asked if it was Berchmans. The figure replied, “Yes. I come by the order of God. Your sufferings are over. Fear not.” He then disappeared. Wilson was completely healed, to the shock and delight of the entire convent.

Mary was able to join the order, and set about writing the account of her healing and collecting the testimonies of the doctors and sisters that had administered to her during her illness. Her report would be crucial for Vatican officials investigating the miracle for Berchmans’ canonization. Berchmans actually appeared to Mary once more while she was well, to say he was satisfied with her work, to obey the rules of her order and that she would die before she finished her novitiate. Mary died in August of 1867 of a cerebral hemorrhage. She is buried behind the convent with a simple marker: MARY WILSON, RSCJ, 1846-1867 (MIRACULEÉ). John Berchmans was canonized in 1888.

A Cloud of Witnesses

I wish I could say I had a visitation during my retreat. I wish it had been the handsome John Berchmans. Or just one of the many gay members of the order who had struggled and prayed in the rooms where I was staying. I like to think they were there anyway. That some residue of their spirits saturated the air around me as I prayed and discerned in the Ignatian way—a cloud of witnesses who had made my being there as an out gay man possible.

The staff and my fellow retreatants couldn’t have been kinder or more welcoming as I talked to them about my own story, including mentioning my husband. They even encouraged me to be the reader for the scripture lesson during one of the two masses that weekend. All that study of psychology and the complexity of desire has left many in the Jesuit order more attendant to the reality of human sexuality, even if the official policies of the Vatican have not shifted. But with the election of the first Jesuit pope, who knows how things might change?

Next spring the Center will hold its first gay men’s retreat. For the first time, gay men will be allowed to walk the halls of the old college and stroll the grounds of nineteenth century farmland without wearing the false masks of intolerant religion. In a way, it will be their chance to reclaim the sensuality of the place. Where the musty wood of centuries-old oaks mixes with the florid scent of azaleas. Where the humidity of the damp ground rises up and leads to sweat and perhaps the shirtless breakdown of modesty. Where at last their bodies can be at one with their surroundings and not at war with themselves. Perhaps they will even sense the applause of a cloud of witnesses, hundreds of gay spirits, watching over their prayers with envy and astonishment.