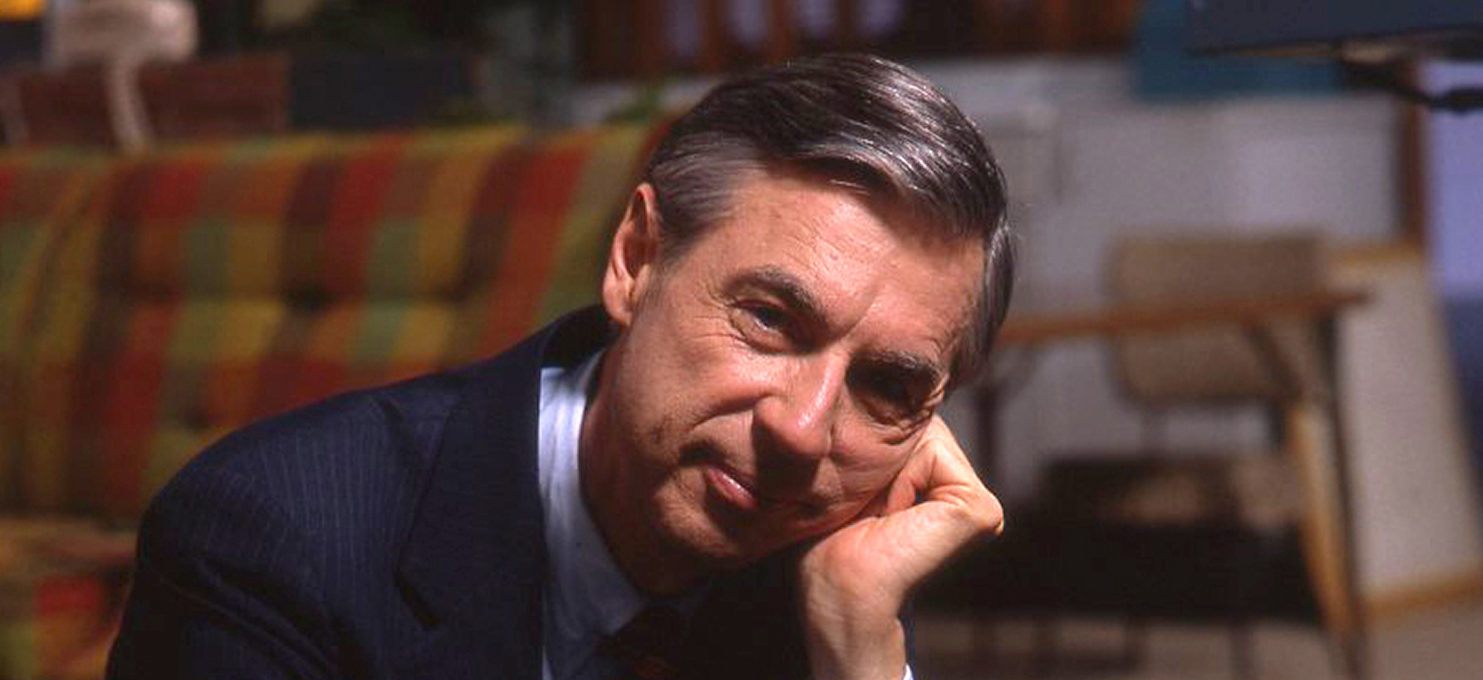

Won’t You Be My Neighbor is a documentary about Fred Rogers and the unlikely phenomenon of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. It is simultaneously a film about the soul of America and what we have become in the years since his passing. In these divisive days, it should be required viewing for all Americans.

Using home videos, clips from and behind-the-scenes footage of the show, and interviews with Rogers, his family, and colleagues, Academy Award-winning director Morgan Neville paints a portrait of a Protestant saint (if that part of the Christian church ever decides to have them, Rogers should be our first). A deeply religious and spiritual man, Rogers had no difficulty integrating his personal faith with his professional life and work. As it should always be, his faith was the heartbeat of his public persona, not its skin. An ordained Presbyterian minister, Rogers’ Christianity was motivated by Jesus’ central teaching to love your neighbor as yourself. Beyond this, his own life overflowed with the fruits of the spirit along with a deep love of, respect for, and passion to protect children. It is difficult to listen to Rogers’ speak about children and not hear echoes of Matthew 19:14.

That Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood ran so long and had such influence is something of a miracle. According to one of Rogers’ long-time producers, it was everything popular television—especially children’s programming—wasn’t: quiet and slow with a low budget and crude production values. All of its success was due to Roger’s respect for and understanding of children. One commentator places Rogers alongside the likes of Dr. Benjamin Spock and Erik Erikson in the history of the study of childhood development and psychology.

While we can’t discount the academic influence on Rogers’ work, the film makes it clear that his empathy and love made all the difference. As I listened to Rogers speak about the state of television and its audience, I thought of a statement attributed to David Foster Wallace in the film, The End of the Tour: we are bombarded by images and stories created by people who do not love us. In one interview, Rogers pinpoints the problem with so much of children’s television, namely that its creators value children for who they will become (consumers) not who they are, beloved, gifted children of God.

Throughout, Won’t You Be My Neighbor reminds us of just how progressive Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood truly was and how vacuous so much of children’s entertainment is by comparison. In its first week, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was commenting on the Vietnam War and its small but racially diverse cast had few equals. On top of this, the series, and Rogers himself, were defined by a sense of wonder and a willingness to stop and take stock of our surroundings, whether it was a fascination with a quiet minute or washing a friend’s feet with cool water on a hot day.

As the film draws to a close, one of Rogers’ long-time colleagues speculated that there is no room for nice on television anymore. If we can’t find a way to make time for it and, more importantly, to integrate it into our daily digital and real-world interactions, then we have yet to see the lows to which our discourse will sink. The phrase, “Won’t you be my neighbor,” is, as one minister in the film puts it, an invitation to love. The film itself is an invitation for its audience to do and be better and to be fueled by the same all-encompassing love that defined Rogers’ life and work.