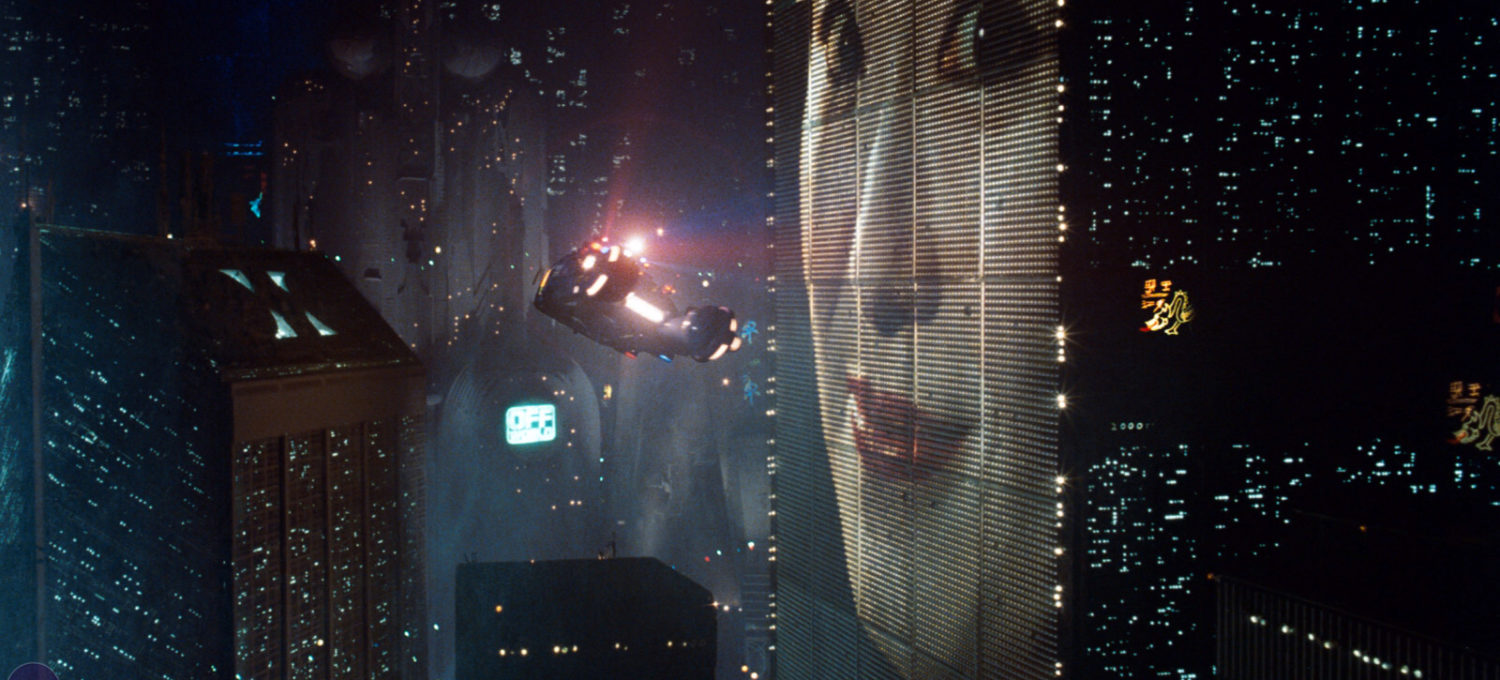

The original Blade Runner is one of the most influential science fiction films of all time. Most noticeably, directors and artistic designers have been drawn to the atmospherics of the film. Blade Runner took the “used future” look George Lucas developed so successfully for Star Wars and brought it, quite literally, down to earth. Even as we approach 2019, the year in which Blade Runner is set, it’s hard not to imagine major American cities like Los Angeles having a dark dystopian future. Director Ridley Scott and his design team combined elements of film noir and science fiction to create an indelible look, and the definitive setting and atmosphere for the many film adaptations of prolific science fiction writer, Philip K. Dick.

But another area in which Blade Runner still has tremendous influence is in our perception of our possible future progeny: artificially intelligent human-like androids. In Star Wars, the androids are safely robotic, waddling or rolling around and possessing strangely neurotic programming. Hardly the type of creatures to turn on their makers. The androids in Blade Runner, however, look like us. They’re “replicants” or “skin jobs” that can blend in with the human population, even though they have superhuman strength and an unsettling capacity for sex and violence. This concept of dangerous androids has affected science fiction from the Terminator films to Battlestar Galactica, and may even be influencing our current fears about A.I. as it becomes more technologically tenable.

Re-watching Blade Runner: the Director’s Cut (well, sort of, it was on SyFy so they cut the sexy parts out) I was struck by how close the portrayal of the replicants hews to a Fall/Redemption theology. Limited to an impossibly short lifespan of four years, the small band of escaped off-world replicants run amok in Los Angeles searching for a fountain of youth rather than accepting their fate and enjoying what they have left of life. In the process, however, they begin to take on some qualities of human reflection and perhaps even guilt for the violence and manipulation they’ve done. The most fearsome of the replicants, Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) paraphrases William Blake, “Fiery the angels fell. Deep thunder rolled around their shoulders… burning with the fires of Orc,” and expresses remorse: “I’ve done… questionable things.”

Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) the bounty hunter whose job it is to track down and “retire” (a euphemism for “kill”) the escaped replicants also goes through a transformation—perhaps he might be a Saul-to-Paul figure, the former persecutor who comes to love and even identify with the replicants. He falls in love with a beautiful replicant named Rachel (Sean Young) and suddenly he can’t view them as inhuman anymore. He begins to be disgusted by his job.

There’s even a sort of (used, dystopian) Trinity in the film. Batty “meets his maker,” Dr. Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel) and Jesus-in-the-Garden-like, asks for more life. Tyrell isn’t much of a benevolent creator, more of a greedy capitalist, and his “no” to Batty’s request is met with a horrifying death. Later, as Batty becomes more capable of empathy, he has a moment of redemption at the end of the film in which he saves his tormentor, Deckard. And in case we missed the symbolism, a nail is driven through Batty’s hand. When he dies, he releases a replicant white dove—a used, dystopian Holy Spirit—into the gloomy Los Angeles sky.

One of the problems I have with Fall/Redemption theology is that it precludes the possibility of a better future by human action. It discounts the possibility that as our species goes through physical evolution, we may also evolve socially and morally. The debate over the human potential for moral progress is an old one, and I won’t rehash all the points here. But Fall/Redemption theology comes down on one particular side—human nature is essentially unchangeable, and as our technological abilities advance, inevitably, so will our capacity for destruction. Blade Runner and its progeny, and before that 2001: a Space Odyssey, seem to take it as a given that human-generated AI will have all the same moral failures and lack of capacity for empathy as humans at their worst. From a morally compromised creator will come an even more compromised creation.

But what if that’s not the way it has to be? What if AI has the potential to improve on humanity, or to enhance it? What if, through careful engineering, we are able to (re)produce intelligence that is both more capable, and has a better sense of morality and compassion than we humans? This is by no means guaranteed, and films like Blade Runner offer a stern warning against glib techno-utopianism. But if utopia is one extreme, dystopia would seem to be the other. Maybe we can achieve something in the middle. Not a perfect future, not a broken down “used” future, but a future that is slightly better—a little more thoughtful, benevolent, and kind—than what we have now.