Richard Lindsay gives us another great review, but this time, he takes us to Broadway with the revival of Equus. Sounds like anyone living in/near New York City or planning a vacation should definitely see this.

London production viewed in March 2007 Gielgud Theatre

Broadway production viewed in January 2009 Broadhurst Theater

Equus starts with the revelation of a horror: Alan Strang, a boy of seventeen, has blinded six horses with a metal spike in the stables where he works. And the heroic psychoanalyst Martin Dysart is the one, the only one, “…there really is nobody within a hundred miles of your desk…,” who can help him.

Equus starts with the revelation of a horror: Alan Strang, a boy of seventeen, has blinded six horses with a metal spike in the stables where he works. And the heroic psychoanalyst Martin Dysart is the one, the only one, “…there really is nobody within a hundred miles of your desk…,” who can help him.

It seems a bit quaint, really. Horses? Not humans? Sick, but not the worst we’ve seen from a seventeen year-old. Psychoanalyst to the rescue? In this day and age?

The accepted line on this revival is that it’s a play past its prime: overarching theories of psychology and mythology not having aged well in a postmodern world. It’s all a little too Jungian. As I mentioned in my review of West Side Story, there’s fine line between making a piece of art relevant, and dooming it to datedness.

But I don’t think that’s the case with Equus. Strang is the classic postmodern kid. (“He can hardly read. He knows no physics or engineering to make the world real for him…no music except television jingles…”) As a character he fits in as easily with Generation Y as Daniel Radcliffe and all the Potterites, now grown, that come to the theater to watch him perform. The Millennials are a generation that, despite the blessed coddling of being Baby Boom children, have watched several of their peers carry out unspeakable acts of terror. Would that we had a Dysart to get behind the minds of the Columbine and Virginia Tech shooters, real-life Alan Strangs for whom the drugs and interventions didn’t work.

In the interim between the West End and the Broadway productions, Radcliffe has grown into the role. In London, he seemed a little like the precocious drama lab rat who’d won himself the plum part in the school play. Adolescent angst not being the hardest thing to summon at 18, Radcliffe now shows himself to be a more accomplished actor in his repression of that rage. His stage presence expands as he relishes the strangeness of Strang, stealing wild looks at the audience between lines.

Viewing the London production, I was riveted by Richard Griffiths. Seeing him again on Broadway, his world-weary psychologist seemed more nonchalant than the material demanded, especially in the first half. But as an audience we must appreciate his ability to toss off the strident and elevated language of the play as though it originated in thoughts fresh from his head – as when Dysart invokes a recurring dream in which he is a sacrificial priest, cutting out the insides of children and splattering their entrails on the ground for other priests to read as oracles. Griffiths relates this gruesome tale – a child psychologist’s midlife crisis, no doubt – with off-the-cuff irreverence and humor. I can’t imagine sitting through a bombastic performance of the same by a barely on-the-wagon Richard Burton as happened in one incarnation of the play in the 70’s.

The character study and questions of society and religion are what make the play tick. The plot itself and the process by which Dysart deduces the meaning behind the crime, based on clunky analysis of Strang’s home life, don’t do much. The hysterical parents, doomed to spend their time on stage revealing acres of Alan’s background, were unbearable to watch in both productions.

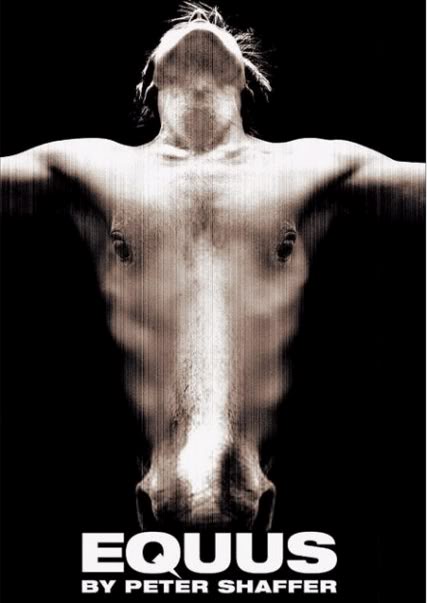

Interspersed with the psychological detective work are scenes of terrifying fantasy involving the horses. They are performed by muscular men in brown velvet suits, wearing wire horse-head masks, and balancing precariously on steel hooves. The horses act as a stamping, whinnying Greek chorus, judging Alan against some abstract standard of normalcy. Leading into the intermission, Strang re-enacts a riding scene by mounting on the back of one of the horse-men-an athletic feat accomplished with guy-wire and a spinning stage and lights. The scene ends with the shirtless Strang’s arms outstretched in orgasmic ecstasy.

Interspersed with the psychological detective work are scenes of terrifying fantasy involving the horses. They are performed by muscular men in brown velvet suits, wearing wire horse-head masks, and balancing precariously on steel hooves. The horses act as a stamping, whinnying Greek chorus, judging Alan against some abstract standard of normalcy. Leading into the intermission, Strang re-enacts a riding scene by mounting on the back of one of the horse-men-an athletic feat accomplished with guy-wire and a spinning stage and lights. The scene ends with the shirtless Strang’s arms outstretched in orgasmic ecstasy.

Dysart concludes the boy has been worshiping these horses, and he’s beginning to get a little jealous. “That boy has known a passion more ferocious than I have felt in any second of my life. And let me tell you something: I envy it.” Dysart begins to wonder if he is really just trying to make Strang “normal” — acceptable to society, an “ardent husband – a caring citizen – a worshiper of an abstract, unifying God.” As much as he realizes the boy is in pain and must be helped, he torments himself: “Can you think of anything worse one can do to anybody than to take away their worship?

The best parts of the play come in the analyst office stand-offs between Dysart and Strang. The stage is abstract – raked, with a rotating disk, and four pillars moved as needed by the actors to evoke furniture – a bed, a desk, a consulting couch. On top of the rotating disk, the stage forms an elevated plus-sign cross, lifting up the religious nature of the agonizing struggles of the two characters. The play explores the pagan connection between religion and theater. Never have I had a more religious feeling in watching a “secular” play – audience members in their seats above and behind the stage leaning their arms on the rails like angels fascinated by the human drama unfolding below – as though the deepest demons of humanity were being exorcised there in the theater.

As Christopher Hart’s Sunday London Times review from March 4, 2007 states, “There is the added historical irony, which Shaffer could not have foreseen when the play first appeared in 1973, that our too cosily secular, materialist culture has been shaken, some three decades later, by gangs of Alan Strangs: disaffected youths who think in a religious idiom terrible and strange, and yearn to make blood sacrifices on buses and trains, with backpacks of explosives.”

But this is more than “historical irony.” Nowadays, Americans find themselves lectured by British atheists like Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins for their senseless adherence to religious belief. These anti-religionists make no distinction between the demands of an animalistic Equus god and the “abstract and unifying God” that Dysart denounces. They are secure in their faith as any Southern Baptist – their materialist religion convinces them that by sheer polemic, they can eliminate whatever God-shape that has formed in the human psyche over centuries of evolution. They propose a revised history, scrubbed clean of the horrors committed in the name of religion, as though this is any more logical than history without the motivating human obsessions of hunger, sex, or fear. When the human striving for divine transcendence is repressed the result is a lot closer to Strang’s night/mare than some kind of rationalist utopia.