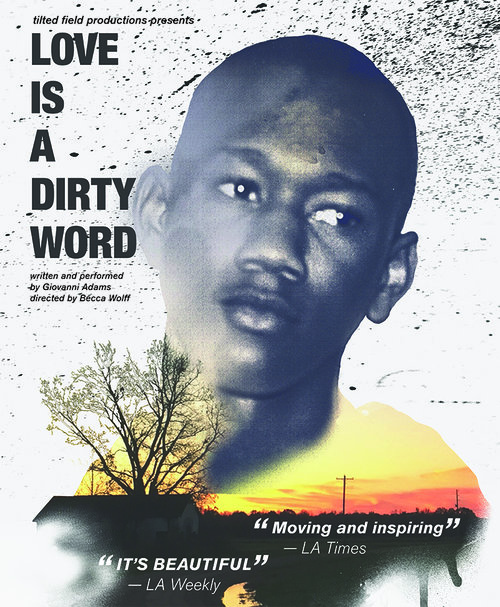

This is a long-overdue review of Giovanni Adams’ one-person show, Love is a Dirty Word, which ran in June of 2017 in Los Angeles and November of 2017 in San Francisco.

Religious precociousness is one of the unacknowledged features of queer childhood. Religion provides the perfect playground for extraordinary queer gestures: dressing up in the vestments of acolytes and altar servers; music making—especially singing; the mastery and recitation of esoteric knowledge like bible verses and creeds; enrapturing an audience through testimony, and, if one is called, preaching. Undisclosed, the queer child is the darling of the congregation. It’s only when they name themselves that there starts to be trouble.

This was the conclusion (and mirror-like recognition) I came away with after watching Giovanni Adams’ one-person show Love Is a Dirty Word at Z-Space in San Francisco last November.

Written by Adams and directed by Becca Wolff, the show recounts Adams’ childhood in Jackson, Mississippi during the 1980s and 90s. On a stage set that evokes his grandma’s “Delta Blues mansion” he takes the audience on the narrative journey of a too-smart kid in the Deep South with a watchful mother and incarcerated father. He recounts harrowing details of his sexual abuse at the hands of older boys, his academic success that took him to Yale, his young adult explorations of sexuality. Throughout the story, an inner voice continues to haunt him, telling him, “You are too dirty to love.”

But what stuck with me was the recognizable pattern of a queer boyhood. Some of the markers of Adams’ queer boyhood have become by now almost cliché: the Easy Bake Oven, the interest in ballet and music, the bumbling attempts at sports. In one of the funnier scenes in the play, he tries to describe to his disbelieving uncles and male cousins that he has found success as an athlete as the coxswain for the Yale lightweight crew. “You mean you don’t even row?” they ask through their laughter.

But where I felt the laser-like connection with the younger self Adams portrayed on stage was in his relationship to religion. Despite many churches’ continued rejection of their queer members, Adams boldly claimed his faith’s blessings for himself. He recalls with joy (and reenacts the scene) of the pastor of his church preaching himself into a sweat as deacons surround him fanning him with their handkerchiefs. He tells about getting in trouble with his grandma for taking communion before he was old enough to be baptized— and has no shame in telling the tale. When it is time for him to get baptized, he’s the first in line, barely waiting for the Come to Jesus hymns to start before he presents himself at the immersion tank in the church.

I also took communion before it was technically “allowed,” although I went through channels—asking our church session for special dispensation. I also felt the thrill of standing before the church and speaking, and on a few Sundays, commanding the massive instrument of the church organ. It was the joy of my preteen life to don a white surplice and cross necklace to serve an acolyte in my church. To my continual consternation, I could never seem to get the other boys to take the task as seriously as I did.

I wondered, as I watched the show, how much the coastal California audiences got the centrality of faith to Adams’ story. If maybe they saw his church experience as an anthropological feature of being black in the South—something to be outgrown and put aside once he came to more liberal climes.

Even if his family questioned the sports-worthiness of his sitting cox for the Yale crew, Adams’ athleticism as an actor is unmistakable. He maintains a breathless pace on stage, performing nearly without a break for 75 minutes. He spits out lines with rhythm inspired by the spoken word style of poetry slams. He embodies voices and gestures from his mama and daddy, relatives, friends, lovers, and abusers. He sings music that comes from the American songbook and his own compositions. (The action on stage and Adams’ singing is accompanied beautifully by the guitarist Arturo Lopez.) Whether digging in a pile of dirt left on the stage to find his lost inner queer boy, stretched out on a bed remembering early sexual experiences, or curled naked in a bathtub wondering who will love him for real, Adams produces an engagingly physical performance.

At the end of the play, Adams digs through the dirt of his Mississippi childhood and finds a school picture of himself as a boy and embraces it, having learned to love the queer boy who became the man on stage. It’s an excavation we all have to make. But doing so in the context of religious queer childhood takes a special leap of faith.