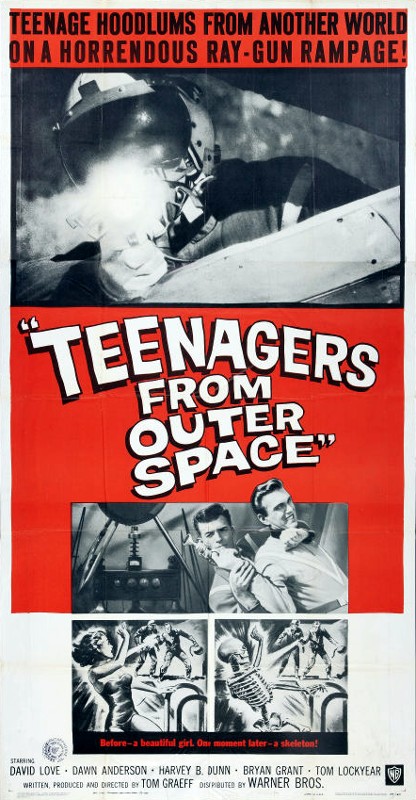

Adolescence has always been susceptible to movie exploitation. In the postwar era, when the idea of an interim stage between childhood and adulthood was new, just putting “teenage” in a title added a hint of moral panic. I Was a Werewolf sounds like a medical problem; I Was a Teenage Werewolf evokes the horror of hormone-wracked bodies out of control. A crime wave is bad enough, but a Teenage Crime Wave raises the specter of juvenile delinquency. Even a movie like Teenagers from Outer Space added an exploitation element to an otherwise unexceptional alien invasion movie.

Most of the teen movies of the 50s and 60s spoke to adult fears of the hordes of Boomer children reaching reproductive maturity, with little sympathy for it was like to actually be a teenager. Exceptions like Rebel Without a Cause were rare. Even the “serious” teen films of the 60s and 70s, like Splendor in the Grass, and The Last Picture Show still had an exploitation element. Hit teen films in the later 70s were mostly horror (Carrie, Texas Chainsaw Massacre) or nostalgia for the glory of the filmmakers’ teen years (Grease, American Graffiti).

Writer and director John Hughes broke new ground in the 1984 with Sixteen Candles. Samantha Baker’s (Molly Ringwald) story includes a boy she had a crush on who doesn’t know she exists (Justin Henry), her parents forgetting her sixteenth birthday, and getting hit on by the school geek (Anthony Michael Hall). In other words, real teenage problems, with no drag racing, pool party sex orgies, monsters, or alien invasions.

John Hughes films (the name became the genre) had an everyteen quality about them, but hardly represented the full diversity of adolescent Americans. For one thing, the casts were almost entirely white. They generally came from upper middle-class or wealthy families. (The Hughes-written Pretty in Pink (1986) was one of the few to bring class into the story.) The main characters had a sense of style that was more mature and self-aware than most teenagers, whether it was trend-setting fashion, music by the Psychedelic Furs and Peter Gabriel, or Ferris Bueller’s uncanny ability as a seventeen year-old to perform both early Beatles and Wayne Newton. But the style added an aspirational element to the films. The movies reflected the real lives of teen audiences, but also projected the lives they wanted to live.

Even so, there was little chance these highly stylish, yet relatable, teens would ever step far outside the bounds of suburban, white, middle-class expectations, by dating someone of a different race, say, or by coming out as gay. Which is why Love, Simon is both a groundbreaking film, and a relatively ordinary teen movie. There could only be a light teen comedy with a gay character at its center when being gay was within the scope of “ordinary” teen behavior.

Although I was in my early 20s when I came out, during that time I found myself searching for a gay John Hughes movie that might help me retroactively process having been a gay youth. In the late nineties in America, a film like this was nonexistent. The closest I came were a pair of British films, Beautiful Thing (1996), and Get Real (1998).

Beautiful Thing is set in a public housing project in East London, and involves a romance between two working class boys. The relationship between Jamie (Glen Berry) and Ste (Scott Neal) is innocently swoonworthy, and the sweet soundtrack featuring Mama Cass has them slow dancing together publicly in the courtyard of the housing project by the end. But what really hit home for me was the fiercely protective love of Jamie’s mother Sandra (Linda Henry) for her gay son. Realizing the love of my own mom was just as fierce helped me to have the courage to come out to my parents.

Beautiful Thing was so formative, that when I had the chance to go to the UK more than ten years after the film came out, I went to the Thamesmead Estates just to see where it was made. Despite its brutalist concrete coldness, the place had an aura of romance for me after renting the film so many times during my early 20s.

Get Real is set in a middle class London suburb. It features the classic teen movie trope of the geek falling for the jock. In this case, the geek is a student journalist, Steven Carter (Ben Silverstone) and the jock is a track star, John Dixon (Brad Gorton). The film is both earnest and humorous, as Steven and John initiate a secret romance. Despite a moving coming-out speech by Steven during school prize day, John is unwilling to come out and give up his position of popularity at the school. The two end up splitting up at the end.

It was a nice enough story, but when I first watched the film, it seemed like it was missing something. I was surprised when I later saw the play Get Real was based on: What’s Wrong with Angry? by Patrick Wilde. It was a far more controversial piece, addressing discriminatory age-of-consent laws for gay youth in Britain and Section 28, a Thatcher-era “Don’t Say Gay” law.

A few American films have mimicked other teen movie types in the last twenty years. Edge of Seventeen (1998), written by Todd Stephens, is firmly in the nostalgia genre, taking place in 1984, with a “Totally 80’s” soundtrack. But this is hardly a light teen comedy—the main character gets raped in the back seat of a car, and eventually becomes somewhat of a barfly. Another Gay Movie (2006) was written and directed by Stephens as a parody of the raunchy American Pie teen sex comedies. Mimicking the infamous pie scene, the main character in Another Gay Movie has pastry coitus with a quiche. G.B.F. (2013) is a sassy high school comedy in the style of Clueless and Mean Girls. The main character, Tanner Daniels, (Michael J. Willett) is outed at school, and rather than being rejected, becomes a token “Gay Best Friend” to three popular girls. Tanner has to struggle to stay true to himself against the expectations of what a gay man is supposed to look like and act like.

Love, Simon is of a completely different character than these films. It closely follows the John Hughes model in style and story arc, telling a story of earnest, deeply-felt adolescent experience.

Simon Spier (Nick Robinson) says he’s “just like you,” except for his “big-ass secret” of being gay. Primed by “watching bad 90’s movies” with his friends, he has come to the conclusion that he “deserves a great love story.”

Simon’s claims of being “just like us” get some eye rolls when we meet his gorgeous psychologist-mom (Jennifer Garner) and hunky yet emotionally sensitive dad (Josh Duhamel). He lives in a wealthy suburb. His parents buy him a car for his sixteenth birthday, which he uses to cruise around and get iced coffee with his diverse group of friends. In other words, he has a dream life for a high school student—except that part about being in the closet.

Simon also checks the John Hughes boxes for a kid with style beyond his age. The Radiohead and Elliot Smith decorations in his room indicate his “Very Serious Teen” status. He also listens to The Kinks on vinyl, and e-mails a friend a Jackson 5 song that came out about thirty years before he was born.

His life begins to change when a student named “Blue” confesses that he is gay on a “secrets” page for his high school. Simon takes a chance to reach out to Blue through e-mail, and they begin an anonymous conversation about their struggles with coming out, and eventually start to have feelings for each other.

After the set-up of an online romance, Love, Simon follows a pretty ordinary story arc. There’s intrigue over which of the boys at school might be Simon’s secret online crush. Is it the hunky waiter at Waffle House? (Joey Pollari) The sensitive piano player in the drama club? (Miles Heizner) The handsome party boy who played Kid Flash? (Keiynan Lonsdale). There’s a blackmail subplot as an obnoxious student, Martin (Logan Miller) threatens to out Simon with screenshots of his secret messages with Blue. There’s major friend drama as Simon’s best friend, Leah (Katherine Langford), who carries a torch for him, must adjust to the news that he’s gay. And of course, there’s the matter of Simon coming out to his family—always a wrenching drama, even in the most accepting families.

In other words, the film uses the drama of a typical gay teenager as the plot complications of a typical teen movie. Like every teen comedy, the goal is to overcome the complications and arrive at that magical moment at the end where the two characters who are clearly meant for each other get together. And I can’t stress this enough—this happy ending we all expect from a teen movie has been nearly non-existent in gay movies up until now.

Even in films by gay filmmakers, usually the ending doesn’t come out with the gay boy finding his one-and-only first love. When the two boys at the end of Beautiful Thing slow-danced in front of their neighbors to “Dream a Little Dream of Me,” many critics wrote it off as hopelessly unrealistic.

So it seems somehow fitting that at the end of Love, Simon, Simon is waiting on a Ferris wheel where he and Blue are supposed to meet. It seems to take forever, as he uses up all his tickets and goes around and around the wheel. But finally, Simon and his beau-to-be find each other. He jumps into the car of the Ferris wheel and they kiss, to the applause of their friends, launching a relationship with positive potential for first love.

Simon had to wait a few hours for his great romantic moment on screen. Some of us have been waiting on that scene for more than twenty years.