Two weeks ago, I found myself subbing in as backup quarterback when Rev. Jim Friedrich, hobbled by back pain, couldn’t make it to Berkeley to teach his January intersession course on Jesus films. Jim has been obsessed with these films since he was a kid on the set of the low-budget (but well-received) Jesus film Day of Triumph (1954) his father produced. It was a challenge for me to take over a course on two-days’ notice, but I jumped in and we had a great class. Here are a few observations on watching clips and complete films of seventeen Jesus movies.

- Jesus on film is always a product of his times. Jesus in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1927 silent epic King of Kings was portrayed as a figure of order and masculine stability in a time of rapid social and industrial change. He was the antidote to the confusion and moral uncertainty of modern life.

- Jesus in midcentury films like The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) and King of Kings (1961, no relation to DeMille’s film) became a man for all people and a symbol of peace during a time of global political conflict.

- Jesus in the 70s, particularly in Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar (both 1973) became an anti-establishment figure—a hippy and a rock-n-roll rebel.

- Jesus in the 1980s became a locus of controversy through “heretical” Jesus films like The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), and Jesus of Montreal (1989). The latter also portrayed “Jesus” as an artist with a healthy dose of anti-materialism during the Reagan era.

- Jesus in the 2000s became a field general in the culture wars in The Passion of the Christ (2004) and Son of God (2014).

- In The Cinematic Savior: Hollywood’s Making of the American Christ, Stephenson Humphries-Brooks characterizes The Greatest Story Ever Told as the Jesus story of mainline liberal Protestantism. I tend to agree. The focus is on Jesus’ teaching, with only one miracle, the raising of Lazarus. Instead of filming in a location resembling the Middle East, it was filmed in the American West, making it look more like a John Ford film than a biblical epic. Filmed in the never-quite-successful three-camera surround technique of Cinerama, it’s a massive, lugubrious Jesus film overstuffed with Hollywood cameos.

- Jesus of Nazareth, the Franco Zeffirelli-directed miniseries is the Episcopalian or Anglican Jesus film. That is to say it has high production values, exquisite taste, and is extremely wordy. It is overstuffed with cameos of British character actors (who at least can act). Also, the film reverses the American Jesus movie tradition of having British actors play Roman officials. In this film, Americans play Roman officials (like Rod Steiger as Pontius Pilate).

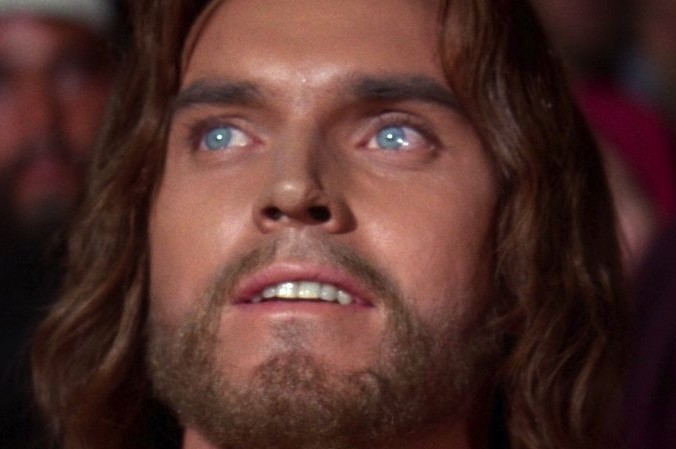

- In almost all of the “classic” or traditional Jesus films, Jesus has blue eyes and Nordic features. (H.B. Warner in The King of Kings, Max Von Sydow in The Greatest Story Ever Told, Jeffrey Hunter in King of Kings, Robert Powell in Jesus of Nazareth, Ted Neeley in Jesus Christ Superstar—although admittedly his eyes are more hazel) In fact, the eyes may have been the main reason for casting several of the actors, including Robert Powell and Jeffrey Hunter. Whenever Hunter wants to demonstrate a dramatic moment, he looks down, and then, like turning on headlights, flashes his eyes. I suppose it was easier than acting.

- Ted Neeley is 74 years old, and is still acting in productions of Jesus Christ Superstar. He can still belt all the notes in the “Gethsemane” scene.

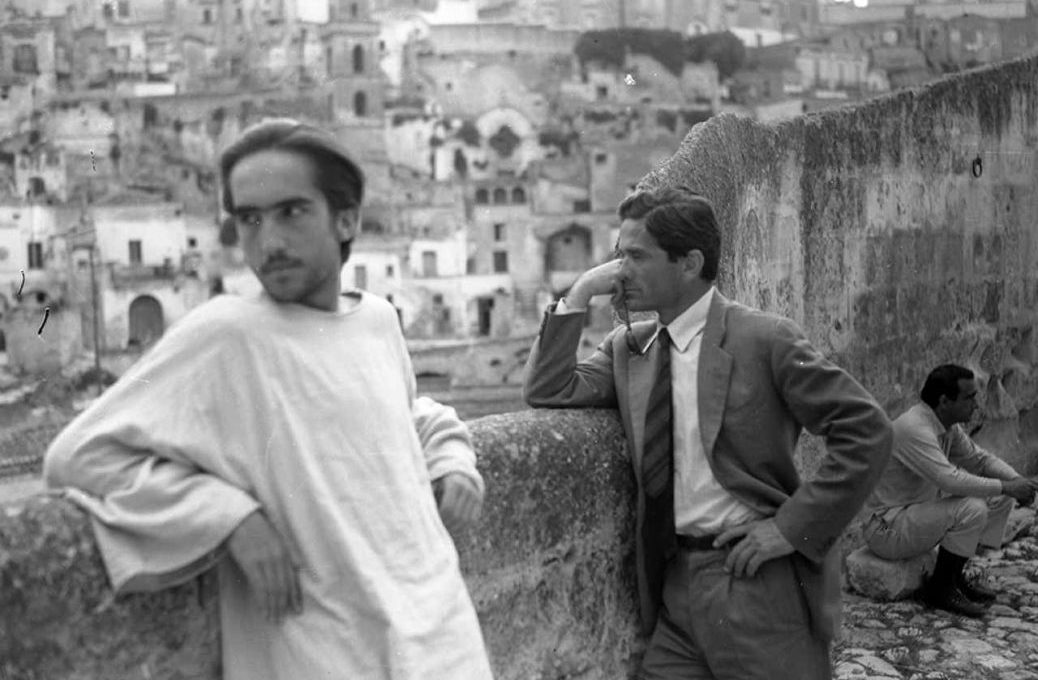

- One of the highlights of the week was watching Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Saint Matthew (1964). Shot in black and white in the Italian neo-realist style, Pasolini, a gay Marxist atheist, used non-professional actors for the film. It’s a rough-cut, rapid-paced, simple telling of Matthew, only using the Gospel and some Hebrew Bible verses for text. The film is accompanied by music as diverse as Bach’s Saint Matthew’s Passion, Blind Willie Johnson, Odetta, and a Congolese folk mass. Spanish economics student Enrique Irazoqui was only nineteen years old when he delivered his firebrand performance of Jesus.

- Pasolini used none of the narration passages in Matthew, moving the story along with dialogue and action. This means certain scenes like birth narrative are almost entirely silent, as Joseph and Mary have no dialogue in this portion of Matthew. In recent years, the film has been embraced by the Vatican, with the papal state’s official newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, calling it the best Jesus film of all time, and “a performance that touches a sacred chord and is inspired by a sincere realism.” The film captures perhaps better than any other Jesus movie that early Christianity was a movement of the poor.

- My opinion is the best format to watch this film is with English audio overdub. Sitting through all that rapid Italian while trying to follow the English subtitles is exhausting. Unfortunately, there is not a really good DVD release of the film in American formatting. One version has English overdub, but has been colorized and shortened (talk about heresy!) and has the original Italian as a DVD “extra.” If you have an Amazon Prime membership, you can watch the full black and white version with English overdub for free with your subscription. Click here.

- Another film that is revelatory in its contemporary adaptation of the Christ story is the 2006 South African film Son of Man. The film is almost entirely in Xhosa, a Bantu language. Set in a country called Judea, Africa, ruled over by a violent dictator and divided by civil war, the film starts with a disturbingly gruesome scene. Mary (Pauline Malefane) hides herself from local militias in a school classroom where all of the children have been slaughtered. She emerges to see a young boy wearing ostrich feathers who tells her she is to give birth to Jesus. She then begins to sing a haunting Magnificat to an African melody.

- As Jesus grows up, he tries to lead his disciples in nonviolent forms of resistance to both the local township leaders and the national dictator. His preaching is intensely political, which leads the authorities to seek to have him “disappeared.”

- The film hits all the major notes of the Gospel stories while retelling the story in the form of an African fable, often with great creativity. (One of the local thugs who questions the mission to kill Jesus is named “Hundred,” just like the Roman centurian, who would have been in charge of 100 men.) Despite almost unspeakable brutality, there are scenes of great beauty, singing in African harmony, and celebration. Mary is not a “meek and mild” handmaiden of the Lord, but a fierce mother who holds local politicians to account for the destruction they are bringing to the community. It is a must-see for Americans to understand the horror of the colonial legacy in the developing world and how Jesus’s message is as revolutionary today as it was 2000 years ago.

- Until teaching this course, I hadn’t really thought about why it’s so difficult to make a good Jesus film. The biggest challenge has to be that Jesus is a self-justifying character. Because he’s Jesus, the Son of God, whatever he does on screen has to be right and accepted by the other characters. Films that have attempted to bring out his humanity—the possibility of mistakes, spiritual conversion rather than instant perfection, resistance to God’s plan—inevitably get called blasphemous. Add to that the fact that the Gospels aren’t naturally cinematic narratives. (As one student put it, with Jesus we start with a birth narrative, get one update when he’s twelve, then skip to age thirty.)

- Seeing the narrative and hearing the words of Jesus over and over again gave me a renewed appreciation for the tradition we Christians follow. His teaching truly was revolutionary, his sacrifice both liberating and salvific. These parts of the story are spiritually powerful–and potentially life-transforming–regardless of what you believe about the supernatural elements of the Gospel. The best films are the ones that strip away the dense theology of 2000+ years and let his actions and words speak for themselves.