In one of my earlier posts, I mentioned that “religious precociousness is one of the unacknowledged features of queer childhood.” For LGBTQ kids brought up in the church, musical performance, altar serving, and church drama, scripture reading, preaching, or testifying, can be opportunities to unleash the fabulousness of queer performance. Church communities are often delighted with their queer kids—until they come out. And if acknowledging their queer spiritual offspring is difficult for congregations, for religious LGBTQ youth themselves, the journey to self-acceptance can take them through hell.

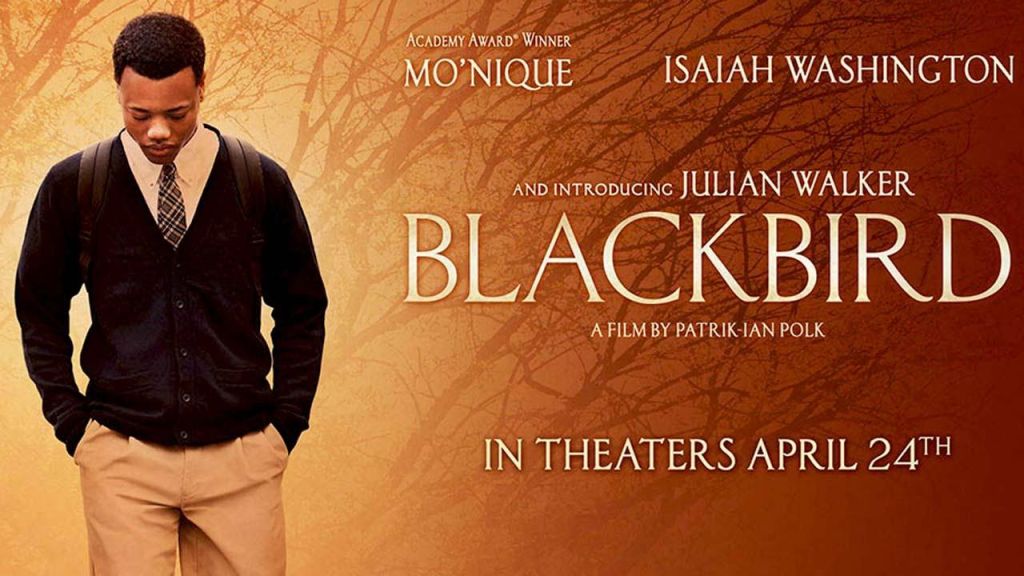

This journey is the basis of Blackbird, a 2014 film by Patrik-Ian Polk that deserves a revisit during Pride season. Polk is the creator of the groundbreaking series about young Black gay men, Noah’s Arc, which ran on Logo for two seasons from 2004-2006, culminating in the theater-release 2008 film Jumping the Broom. Blackbird is based on the novel of the same name by Larry Duplechan, published in 1986. For this adaptation, Polk returns to his hometown of Hattiesburg Mississippi, where the film is set.

Randy Rousseau (Julian Walker), a high school senior, is one of those star kids at his predominately African-American church, where he often leads the choir, his solo voice soaring through such classic spirituals a “Lord I Want to Be a Christian” and “Amazing Grace.” The thing is, he also keeps having dreams where his school and church friend Todd (Torrey Laamar) strips him of his choir robe and makes out with him, leading to a “sticky” ending. Every time he wakes up from one of these dreams, Randy kneels on the floor, begging Jesus to take these feelings away from him.

In his school life, Randy is a mess of contradictions. He hangs out with the arts and drama crowd, including one openly gay friend Efrem (Gary LeRoi Gray). Despite his discomfort with his sexuality, Randy agrees to perform in a gay version of Romeo and Juliet for the school play (“Romeo and Julian”) with his secret crush Todd playing opposite him as the co-lead. Meanwhile, he quotes Bible verses to himself about resisting temptation, like I Corinthians 10:13: “…God is faithful; he will not let you be tempted beyond what you can bear. But when you are tempted, he will also provide a way out so that you can endure it.”

Temptation increases for Randy when he answers a casting call for a student film at the local community college. Again, he’s asked to play a cringingly difficult part, as the victim of sexual assault by another man. (Randy either seems to secretly want to come out, or is a glutton for punishment) His scene partner in this case is a slightly older white boy named Marshall (Kevin Allesee) who makes no secret of his attraction to Randy. Their connection over music and acting and independent film eventually leads Randy to stick a toe out of the closet. He even begins to see the possibility that God might be present in his burgeoning relationship with Marshall.

There’s a subplot in here about Randy’s younger sister having been missing (presumably abducted) for six years. I’m not sure what this adds to the story, except to allow Mo’Nique to reprise her role as the abusive mother from Precious. It also gives his mother the opportunity to blame Randy’s “sinfulness” for the loss of his sister. I’m never sure why Hollywood writers add extreme subplots to domestic dramas. Is it just to turn up the pressure on the main characters? It seems to me a Black teenager from a religious background coming out in the Deep South is a fraught enough situation without slathering on the melodrama.

Isaiah Washington also pops up as Randy’s estranged father. He actually plays the more accepting of Randy’s parents. Considering his notoriously homophobic history, you wonder if his appearance in this film is part of some kind of court-ordered rehabilitation project. He’s such a wonderful actor, it makes you sad he’s such a terrible person.

Julian Walker more than holds his own with these veteran actors, showing off his gorgeous voice and apparently natural acting ability–he was recruited locally for the film as a student at Southern Mississippi State. Since Blackbird, he’s continued to act, in the BET series Being Mary Jane (co-written by Patrik-Ian Polk). One hopes in modern Hollywood there’s a place for openly gay Black actors with natural talent like Walker’s, but we’ll see.

Another note to this film is its lack of resemblance to the original novel by Larry Duplechan. It’s really a different story with similarly-named characters. Randy, known as Johnnie Ray in the novel, is a more confident gay youth—quoting camp movie references and owning his sexual desires. Instead of the Deep South, the novel is set in the Inland Empire outside Los Angeles. Johnnie Ray deals with overt racism when he’s rejected for the part of Romeo, despite being the best actor in the school, because the drama teacher doesn’t want to pair him with a white actress. In terms of his sexuality, his problem is not so much being gay, it’s that he’s too Black, too creative, too much of an artist for his backwards exurban town.

The story of “Randy” and his struggle as a Black gay kid from a conservative religious background in the film version of Blackbird is one that needs to be told. The comments on YouTube, where I found Blackbird being streamed, attest to how vital this film has been for many viewers – and the crying need for more stories about LGBTQ young people of color overall. But I would have loved to see a character as unconventional as “Johnnie Ray” from the original novel come to life on screen.

Finally, returning to the idea of religious precociousness in queer youth, I came to that realization after watching the one-person play, “Love Is a Dirty Word,” by Giovanni Adams, in which he dramatizes his queer Black boyhood, also in Mississippi. He and director Rachel Myers have collaborated on a short film, “2 Black Boys,” based on that play. The piece made the rounds at film festivals last year, including Outfest Fusion in L.A. It adds gorgeous cinematography to Adams’ poetry, leading viewers on an impressionistic journey into the emotional heart of a queer man coming to terms with his childhood. Where it ends up is in a similar place to the play – the need to attend to the queer child inside the adult, the needy kid who just needs to know he is not “too dirty to love.” It’s a beautiful piece, and I recommend watching it on the director’s Web site.