My book, Hollywood Biblical Epics: Camp Spectacle and Queer Style from the Silent Era to the Modern Day, dropped yesterday. Get it on Amazon or anywhere fine books are sold.

My book, Hollywood Biblical Epics: Camp Spectacle and Queer Style from the Silent Era to the Modern Day, dropped yesterday. Get it on Amazon or anywhere fine books are sold.

Continuing now with the “Popping Collars” podcast in which the Rev’s Greg Knight and Betsy Gonzalez and I discuss biblical epics, scripture, and popular culture.

Here’s the link to the whole podcast, which is much more entertaining than reading a transcript.

Again, I offer the caveat that this is a not-at-all accurate transcript, so listen to the podcast if you want to hear what we really said.

Popping Collars Podcast #20: “Once More with Passion” (Part II)

Greg Knight: DeMille was tied to the idea that a movie was a spectacle but he was using scripture as the script so he had to find a way to mix these two things.

Richard Lindsay: To me that’s where you get camp. If something is, say, “queer” it tries to erase a binary but if something is camp it acknowledges that a binary exists and crosses it anyway.

DeMille grew up in a household with a very devout Episcopal father. His father was really convinced that the Bible and lessons of Christian morality could be told in the theater. This was a very controversial notion in the late Victorian era. So he would create these morality tales that would show in theaters in New York City. That was the environment DeMille came up in: he was around the theater and around theater people but also around this very devout dad.

So you see these warring influences in DeMille. On the one hand he was trying to arouse people to a certain piety, on the other hand he was just trying to arouse people. When you have that obvious conflict and someone doesn’t really seem to notice that it’s there, you have camp. It’s very ironic.

DeMille felt the best way to start his Christ film, The King of Kings (1927), was with Mary Magdalene dressed up like a flapper. Her boyfriend Judas has run off with Jesus and she’s going to go find her boyfriend Judas by getting onto chariot which is pulled by zebras. That’s just the way you start a Bible film.

Betsy Gonzalez: That’s what the Scripture does right?

Greg Knight: I’m pretty sure that’s in the Bible. I haven’t read the whole thing.

(laughter all around)

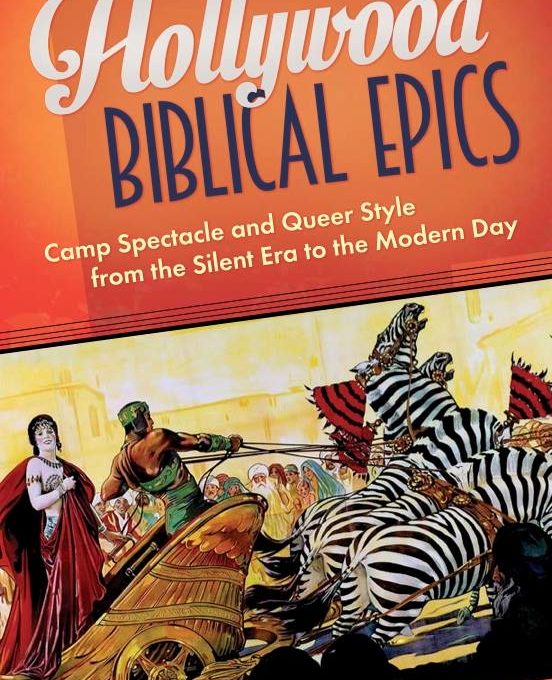

Richard Lindsay: The cover of my book has the image of Mary Magdalene as a flapper on the chariot being pulled by zebras. This was a poster for The King of Kings when it came out in 1927. It’s a Christ story, but the posters says it’s a “Supreme Dramatic Spectacle! Come see the “Supreme Dramatic Spectacle!” And this was the Passion of the Christ of its day.

The first chapter of my book is comparing those two films: The Passion of the Christ and The King of Kings, and showing how really nothing changed in 80 years in the way that these films were received. Both films were seen as absolute Gospel truth; both films received multiple endorsements from clergy that said go out and see this film, this is the story of Christ. There are miracle stories surrounding both films. There are traditions of viewing. The Passion of the Christ is an Easter movie and the King of Kings would also be shown at Easter all over the world. It was very adaptable when you showed it around the world because it was silent and all you had to do was change the intertitles or the words between the film scenes.

What was also interesting was that neither Cecil B. DeMille nor Mel Gibson would’ve been anybody’s first choice to tell a Jesus story. DeMille was primarily known in the 1920s for doing sex and society films. And it was kind of a DeMille requirement that every movie had to have a naked woman in a bathtub.

Greg Knight: It’s in the rider

Betsy Gonzalez: No green M&M’s, and there has to be a naked woman in the bathtub.

(laughter all around)

Richard Lindsay: And so with Mel Gibson, here was someone who’s an anti-Semite, he’s an alcoholic, he’s a pre-Vatican II Catholic and he’s just a violent individual.

Neither one of these directors would have been seen to be great examples of Christians for a lot of people. But the fact that they were so imperfect actually added to the cachet around the films. If these wonderful pious films came from these fallen directors then surely this must have been an act of God.

Greg Knight: The Passion of the Christ is a good example, because it came out on Ash Wednesday and it was like a religious service the way it was set up. Here’s a holy day that we’re going to release it on, it’s Ash Wednesday, so you have the entire season of Lent to go see it. And then leading into Easter we’ll make a big push marketing-wise. And it was like, wait a second is this a movie or is this church? I thought that was a really cunning way of marketing it.

Richard Lindsay: If you get the special edition DVD of The Passion it actually arranges the film in the Stations of the Cross. So rather than simply flipping through the chapters as you do in a normal film you can flip through them as the Stations of the Cross. So it can actually become a home devotional.

Betsy: There was definitely an agenda that Mel Gibson wanted to bring to the Christ story. And it was very different from a Last Temptation of Christ Jesus who doesn’t know what’s going on all of the time. As opposed to being the quiet secretive all knowing Jesus who knows exactly where everything is headed. Where he’s saying, “Oh I know what’s going to happen, everyone. I’m very gentle and kind and beardy so let’s all be together, but something really bad is going to happen so buckle up.” The contrasts in the films speak to us about the different ways that we like to have our faith delivered to us.

Richard Lindsay: My interpretation of The Passion of the Christ is that it had everything to do with the culture wars and the perception of what is wrong with the world, and what is wrong particularly with America. So Jesus in this film is kind of like a superhero Jesus, he’s kind of an action hero Jesus. Jim Caviezel (his physique) is ripped.

And the tendency seems to be that our salvation through Jesus was in his ability to endure pain. I think most people agree that whatever happens in the flagellation scene there’s no human being that could survive that. So the fact that he gets up, and that he keeps getting up, and getting up in order to take more punishment, is significant.

Then you get to the scene with Herod, and Herod always seems to be gay. This was true in Jesus Christ Superstar, and it was also true in The Passion. So how does Jesus deal with this gay Herod? He really just ignores him. He doesn’t talk to him, he doesn’t address him or look him in the eye. He’s this manly man of action and he’s not even going to look at gay Herod and he’s not even going to give him his acknowledgment.

There are some very specific messages that Gibson seems to be sending in that film about his discomfort with various cultural war issues. And this is why the film became such an important cultural war monument. Going to see the film was an act of faith itself. Going to see it over and over again and even bringing your kids, as inappropriate as that was, was also an act of faith.

The discussion turns to an alternate theological interpretation of The Passion, which I address in the book.

Richard Lindsay: After a while Jesus really starts to look monstrous; he really starts to look like something other than human. So what I try to do is take these camp experiences of films [e.g. the horror movie possibilities of The Passion] and put them through a queer lens.

How would you interpret this if you were looking at it from a queer perspective? So what I see in the Passion of the Christ is that Jesus is turned into a monster. And that, in a weird way, is liberating, because it shows him to be in solidarity with people who are considered monsters. With people who are pushed to the margins of the culture, whether that’s because they are LGBT or because they’re immigrants or because they have a drug addiction or whatever. It’s like he has become the monster for us and with us.