You already have an opinion about Thomas Kinkade. If he’s never really crossed your mind, you have an opinion. Hell, even if you don’t know who he is, you have an opinion about him. At one point, Thomas Kinkade was undeniably the most popular, and most profitable, artist in America. If you don’t recognize his name, you’d immediately recognize his style: pleasantly hued scenes of rural cottages or city streets seemingly hazy at the edges like a fleeting but pleasant memory doused in warm, bright light radiating from every window or lamppost. Despite J.M.W. Turner’s original claim to the title, America’s titular “Painter of Light” has been many things to many people – a beloved artist whose accessible work they could proudly decorate their home with or an enemy of the very philosophical pursuit of art. But who was Thomas Kinkade to himself? This is the question Miranda Yousef sets out to explore in her documentary “Art For Everybody.”

Explore rather than answer, of course, because this is an impossible question to answer – a question Kinkade himself couldn’t figure out before he sadly passed. What the film provides, however, is an argument that, whatever it is you believe about Kinkade, a person’s life is always more complicated and fascinating than you assume. The film accomplishes this by juxtaposing Kinkade’s meteoric rise to fame with the revelation that his personal vault of paintings contain a lifetime of artwork radically different than the saccharine scenes that built his empire. For some, this might shake his well manicured evangelical image while, for others, it might finally endear them to the often maligned artist. For those of us who find ourselves somewhere between the two extremes, it provides a tantalizing exploration of a quintessentially American artist – whatever that means, for better or worse.

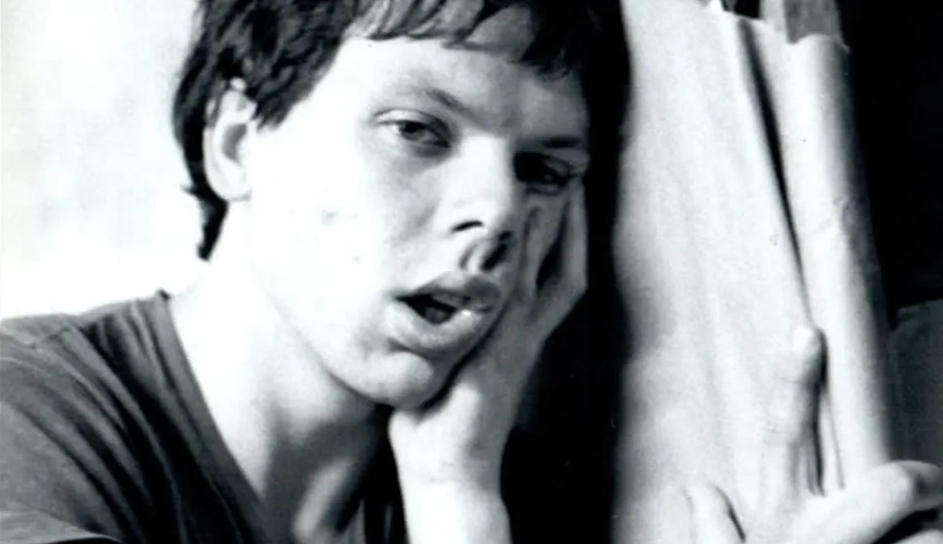

The film covers Kinkade’s whole life and, while it doesn’t dig as much into his tumultuous finals years as you might imagine (possibly out of respect for his family who are heavily involved throughout this film), it is a thorough investigation into the journey of a former art student escaping a tortured youth to become a mall art superstar who flew a bit too close to an idealized sun. To ground the trajectory of the film, there’s a recording of Kinkade in his youth pontificating about the hopes he holds for himself as an artist. It’s clear from these sincere, if at times sophomoric, ramblings that there’s a real sense of desire and passion for the pursuit of art – a desire that so many of his critics failed to see.

Whether you can find it in your heart to appreciate the aggressively inoffensive style he eventually perfected, it’s hard to deny that the personality Kinkade developed to sell his work is, at times, hard to stomach. It seems from the stories told and from the home footage sprinkled throughout, that the endlessly cheerful man of God schtick was in many ways more a part of the sales pitch than not. This image, however, is what most of us knew him as and it’s hard not to judge the art and the artist in similar ways when they’re sold as a package. The political implications of his art – an art doused in nostalgia for a seemingly white world of cheerful colors and safe, warm light – are impossible to ignore. At one point, an avid collector of Kinkade states: “there’s no al-Qaeda hiding in those bushes!” It’s kind of hard not to imagine the whole jingoistic cultural narrative that’s behind that.

Whether Kinkade supported this narrative is perhaps implied but never definitively answered. Either way, Kinkade’s artwork undeniably revels in what professor of art and theology Daniel Siedell calls in the film a ‘world without the Fall.’ There’s almost no complications in this world and everything invites the viewer into a calm sense of sanctuary. At an early point in his career, Kinkade was able to position himself as the safe, Christian alternative to an increasingly dense and dangerously modern art world. Juxtaposed against the infamous “Piss Christ” (a personal favorite piece of mine) it’s easy to see how large swaths of a certain American population would prefer to think about a lovely little garden than the difficult and potentially degrading implications of the Incarnation.

After the film, Yousef stated that she hoped to present an exploration of Kinkade that might reach beyond our typically one sided culture war readings. In this, she more than succeeds. It’s unclear whether Kinkade’s youthful explorations of various styles or his later post-rehab meditations on trauma will set the art world on fire anymore than his pastoral imaginings did, but what they prove is that what you’re sold in this country is rarely the truth. In many ways, Kinkade’s empire was the product of a similar desire that led Andres Serrano to fill up a jar with his own urine and dunk a crucifix inside of it – to find some sense of solace through creation. Kinkade, unfortunately in my opinion, stumbled upon a gold mine and lost a bit of himself as he imagined away his pain amongst all the gentle greens and lovely lavenders. He was an undeniably talented individual who just happened to be a great salesman and chose to hone that skill rather than the other. Whenever the family finally unveils the extent of the vault, the world will have to wrestle with the complicated reality of an artist who sold them an uncomplicated world but, until then, this documentary does a lovely job offering to bring some much needed shadow into his overly bright world.