Let’s get this out of the way first: At the Drive-In were one of the most important bands in my life. They altered my brain chemistry irreparably and defined the trajectory of my musical tastes for years to come. The same can be said of the bands they eventually split into, Sparta and The Mars Volta. To say that I was excited about a documentary covering the formation and career of The Mars Volta would be an understatement so I will try to be as objective as possible…which is a lot more than can be said for the documentary.

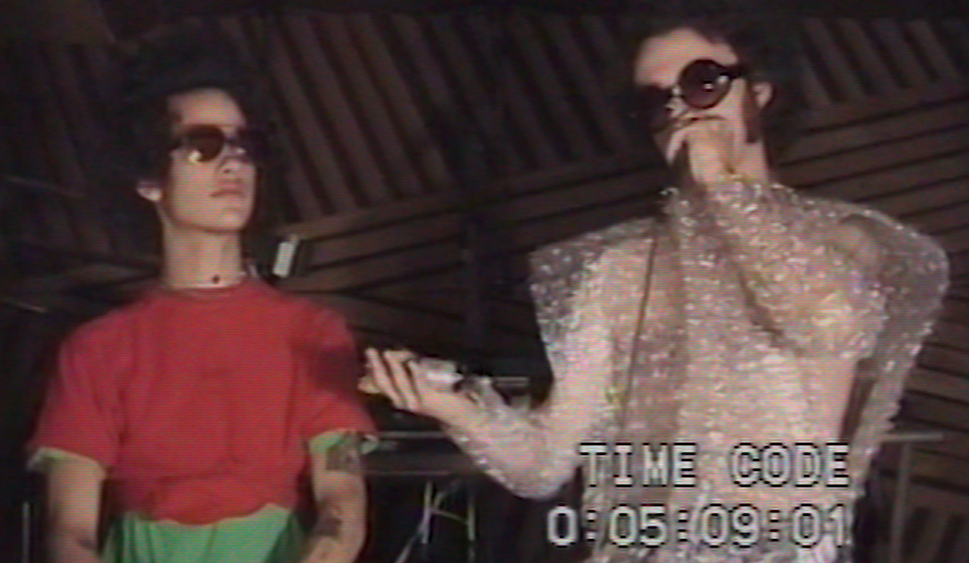

Thanks to guitarist Omar Rodríguez-López’s relentless creative drive, “Omar and Cedric: If This Ever Gets Weird” is composed of scenes culled from hundreds (thousands?) of hours of footage filmed either purposefully or aimlessly throughout their life and career. As such, it is a remarkably deep behind-the-scenes look at who Omar and singer Cedric Bixler-Zavala are as artists as well as friends as they perform skits or explore sounds. For any fans curious about the wild forces that drove the band to create the psychedelic prog-rock masterpieces of De-Loused in the Comatorium or Frances the Mute, this movie will be an absolute treat. For anyone hoping for a clearer insight on At the Drive-In or perhaps later Mars Volta records, well, it might be a bit frustrating.

The movie begins by establishing Omar and Cedric within the tension of their cultural and social upbringing in the punk scene of El Paso, Texas before briefly covering the formation and eventual dissolution of At the Drive-In. Their Latin influences are of course essential to what Mars Volta became so it’s particularly interesting to see how that got juxtaposed against the aggro rock scene they eventually blossomed alongside (if a bit unfair. Sure, Limp Bizkit and the like were big but At the Drive-In meant more for the scene that gave us Thursday or My Chemical Romance). Afterwards, a solid chunk is dedicated to diving into the unrestrained period of sonic exploration that gave birth to Mars Volta. From there, it details the band’s creative ebbs and flows with less focus on the records it produced and more on the tension that arose with Cedric’s personal involvement with the Church of Scientology.

While it is fascinating – and heartbreaking – to watch their relationship morph around their spiritual allegiances, I couldn’t help but feel more curious about how this showed up in the work rather than how it’s presented in the film. The contrast between Cedric’s earnest hope for a faith system that might help reign his wild tendencies ultimately being manipulated by the dangerous capitalist cult and Omar’s spiritually open-minded embrace of his friend’s journey rooted in his own family’s pluralistic spiritual proclivities is worthy of examining – but ultimately the film decides to stick with the broader stokes. For a film that, up until this moment, had been deeply candid, it feels like maybe some of these wounds are still a bit tender to touch. The film eschews exploring how this tension shows up in their later albums and instead takes time to celebrate the much deserved win of Cedric’s wife Chrissie Bixler against the scientology scumbag Danny Masterson before ending rather abruptly. It’s joyous but also strange they don’t then spend time on their recent, far more Latin influenced album.

Another disappointment is the general objectivity of the film. It’s clear throughout that we are really only getting to see things from Omar and Cedric’s perspective. In fact they’re the only voices we hear throughout. I began to feel uncomfortable with this when they go out of their way to paint At the Drive-In guitarist Jim Ward as solely responsible for the band’s dissolution. While the tension between the three is undeniable, the film at times seems to imply some racist animus behind this tension without backing it up. This is made all the more bizarre when, after exploring Omar’s beautiful and heartbreaking romantic relationship with Mars Volta sonic architect Jeremy Ward, they never once mention the family connection. This pattern continues to repeat throughout the film as tensions with various Mars Volta players are portrayed more or less as individuals who just don’t “get it.” After a while, it’s clear that the strength of Omar and Cedric’s bond simply outweighs every one else who comes into their orbit.

None of this, however, ruins the experience of watching the film. As long as you go into it recognizing that the truth is always dependent on how much we’re willing to open up to it, this film is a brilliant look into two of the most inventive and engrossing performers of the past few decades. It is raw and intimate in ways few music documentaries even have the ability to be, utilizing the treasure trove of footage to unfold lives both private and public. Director Nicolas Jack Davies does an incredible job piecing together the footage in a dream-like manic collage of creativity, chaos, and camaraderie. In this way, it’s closest aesthetic companion might be the recent Bowie documentary “Moonage Daydream” but with a more unhinged psychedelic lens. If that appeals to you as a fan of these bands then you’re in for a treat – but I highly doubt you need me to convince you.