We are always on the cusp of death. At every moment, a thin veil rests between us and an infinite abyss. If we are so lucky, it might be pulled back slowly in a grand and illuminating revelation – but it can just as easily be pierced suddenly, fleeing before we are even able to grasp what has happened. We do our best not to think of this fact, distracting ourselves as we do with our busy lives. But for all the work we put into building our lives, it only really amounts to painting murals upon the veil’s surface. No matter how substantial they may seem, they will not remain once the veil is taken away. This truth has fueled religions, psychological systems, and a fair amount of miscellaneous existential dread for millennia but, in our healthiest of reflections, we come to find that there is no substance to this concern. The truth of our ephemeral selves is, undeniably, an inextricable and intimate aspect of life, a part of its beauty. From an unknowing non-existence, hidden preciously in the potentiality of being, we were born – and just as mysteriously, just as easily, do we return. It is in contemplation of this blunt truth that we find the heart of The Salt Doll Went to Measure the Depth of the Sea by New Jersey alt-folk outfit The Low Anthem. It is an album of haunting comfort, like a whispered wave breaking in the dim light of a clear, moonless sky. It is a reflection on death, or perhaps at least standing close to the edge, considering what beauty we might find on the other end.

This album exists in the sharpest possible contrast to their previous effort, Eyeland. But, in doing so, it also serves as an existential companion piece of sorts. A psychedelic experiment in maddening extremes and multiplying textures, Eyeland was an unhinged outpouring of sonic exploration that swung wildly from plaintive folk whispers to deranged electronic hisses. It was born out of a band abandoning themselves to their creative communion, seemingly allowing every bit of light to shine no matter how jagged or potentially jarring. In conjunction with the album the band purchased an old theater, eventually pursuing a multi-media effort that included the production of a play based on the album – itself a reflection on the liminal space of a child’s imagination. It seemed the creation of a band embracing life from every angle, arms stretched wide and eyes closed in faithful excitement. But then, while beginning their tour in support of the album, that excitement came crashing into a pole and lay strewn across the asphalt. Poetically, the band recalls their instruments laying chaotically along the road, traveling back to scene to pick up the shattered pieces that had just previously produced their most cacophonous creation yet. No one died – but death, it seems, was observed. The Salt Doll Went to Measure the Depth of the Sea is in almost every way to opposite of Eyeland – quiet, singular, meditatively and musically minute. Where once life appeared a wild lover, the band seems to have now stepped back in fearful admiration of its rapturousness. It is every bit of an embrace but, this time, it is passive and all together peaceful.

Before we go on, it will be behoove us to consider the eponymous Salt Doll. The tale, for those unfamiliar, goes generally like this:

A journeying doll made entirely of salt stumbles upon the sea. Confused by its ever changing surface, she inquires: “What are you?” The sea answers plainly: “I am the sea!” Still unsure of what this means, the sea offers for the doll to come closer and touch it in order that she might know what it is. The doll obliges, finding that in doing so she has lost a toe. Alarmed, the doll frantically asks what has happened, to which the sea replies: “you have given something of yourself that you might understand me.” Ever the more curious, the doll begins to wade out into the water until finally she has dissolved entirely, exclaiming: “I am the sea!”

We are, of course, the salt doll, drawn to an impossible unknown – a radically volatile void, endlessly enticing. To live is to give ourselves over little by little until, having found ourselves dedicated and diffuse, we are fully consumed. To live is to die and to die is to live. With The Salt Doll Went to Measure the Depth of the Sea, The Low Anthem have created an stunning soundtrack to this perennial spiritual truth.

Despite the sober reality of its inspiration, there is nothing maudlin about this record. There is a lightness, perhaps even a joy, to every track that confronts the unknown not so much with trepidation as with certainty, as uncertain as we can ever be. This certainty is born not out of hubris but of appreciation. Appreciation for the beauty of the surf, dazzling in the light, and for the depths, terrifying in their overwhelming power. Written over the course of 16 days following the crash, the record carries with it all the weight of their confrontation with death. There is no rush to pick up the pieces – only the opening up of a space within which to honor their destruction. In this, the album feels as if it exists to give death its due, recognizing the immensity of its power, the holiness of its absolute claim. Considering this, it might seem something of a miracle that the album is as gentle as it is. But this meditation is purposeful.

Throughout the album, there is a relentless rhythm. Although occasionally provided by minimalist electronic beats, it is more often than not the gentle grainy skip of an old record player. While the meter is not exactly consistent song to song, it provides a soft through line that buoys each song together, bobbing with an even keel upon the churning waves. Singer Ben Knox Miller recounts pulling together the instruments he had left and creating for himself a space filled with hypnotic sound within which to write. What made it to the album is not so much all consuming as it is pervasively comforting. At times, it is an almost unnoticeable undercurrent. The band refers to it as a “subtle energy of circularism” creating “a safe space of time (a constant feeling of return), but some of the space that is opened up is so bare as to be nearly uncomfortable.” Truth be told, it plays like a prayer – like the repetitious invocation of some ineffable holy name that the doll, try as it might, knows that it cannot capture.

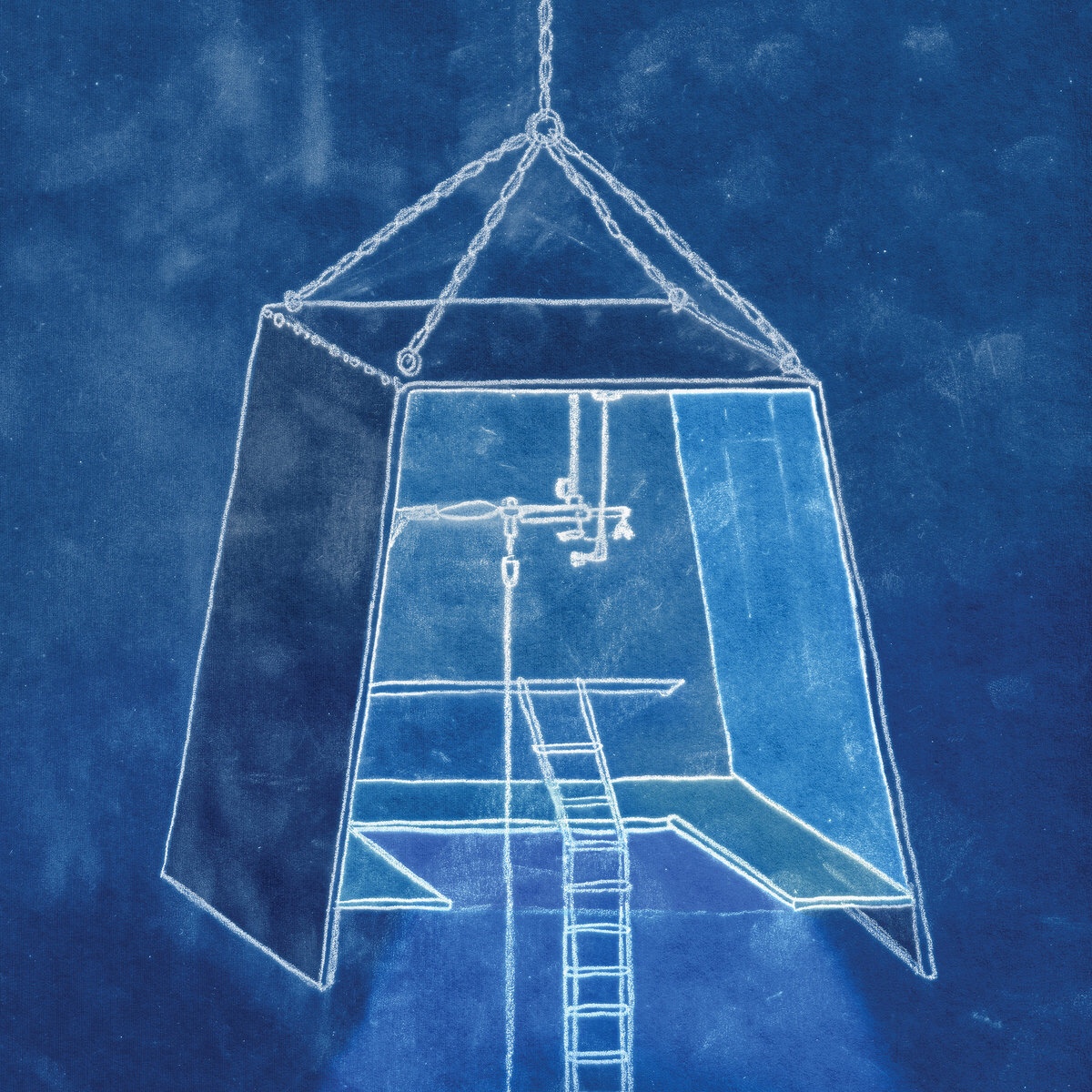

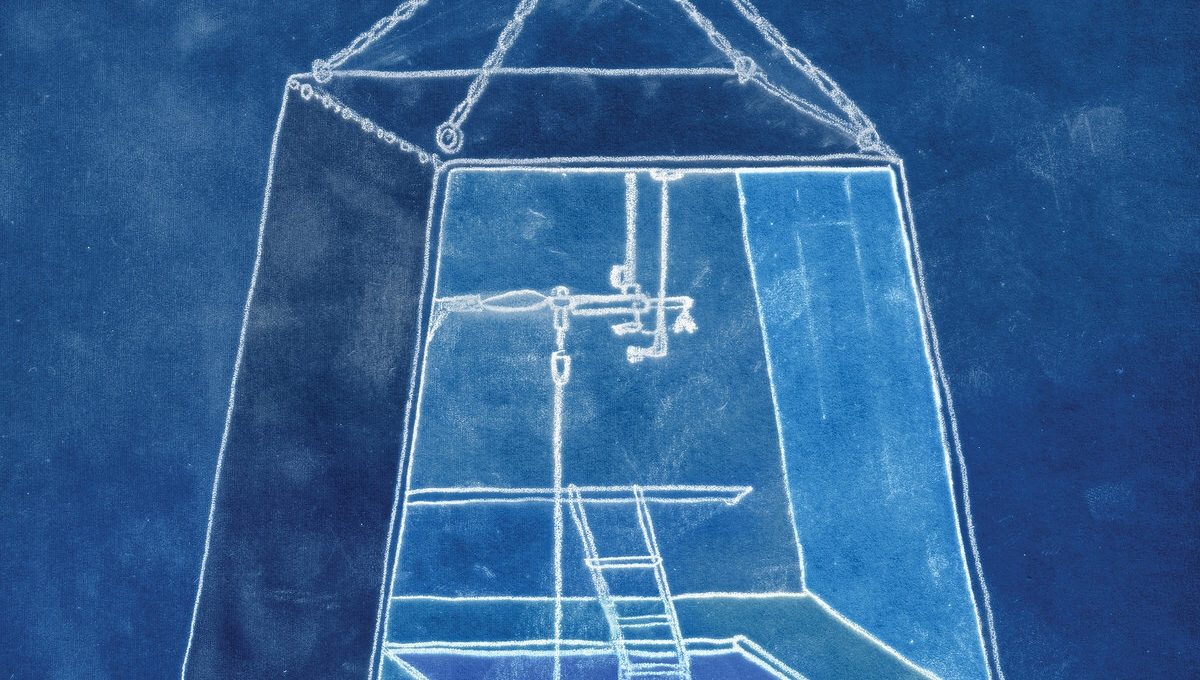

As mentioned before, this is a quiet record, subtlety simplistic but no less rewarding considering the fantastic scale of its tale. In hushed tones laid bare between the incessant rhythm, Miller sings of the Salt Doll’s journey, of the wild ocean topography, of the precipice and the descent. The listener is pulled along with the rhythm and slowly, but ever surely, is lost in the murkiness below. At first we stand on the sand, the remnant of sailor and bird bone alike, before there is a prayer to “give my body back, as I fall.” But the album never quite stays submerged, bobbing back to the surface from time to time invoking the circularity of life’s steady submission to death. There are noble, if fruitless, battles of krill against leviathan and tipsy fireside contemplations on the erratic scribbles of Cy Twombly, pleas for us to “lose our fear, superstition” and to finally, as we all must, release the diving bell. This is the true strength of the record – it makes no claim that we do not at least unconsciously accept. If there is a spiritual dimension to it, it is only in its humility. While annihilation is a forgone conclusion, the sea does not so much demand as it invites. We lose so much in living but the album begs the question – is this not what brings meaning to life, to give it away?

There’s a deeply personal reason this album ended up my favorite of the year that extends far beyond how lush and lovely it is. Over the past year, I have had to step a bit closer to the edge, feeling a piece of me disappear but grateful the Salt Doll has accompanied me. Admittedly, this is just the hubris of youth but I’ve never really considered what might soundtrack my inevitable meditation on mortality. Like everyone, I’ve always known music to be good for soothing a broken heart or for giving weight to ephemeral ennui but it’s a different thing altogether to be confronted with the sure realization that all my precious philosophy could only ever be chaff. The holiness of music is not found in the simple manipulation of mood but is rather in giving weight to the liminality of living. There are plenty of albums I “enjoyed” more than this – but there’s no album I needed more this year as I approach the Sea.